PART 2: If not us, then WHO! ULTIMATE PLAN TO STOP THE WHO (Memorandum of Understanding regarding our stakeholder engagement at the WHO)

This is Interest of Justice's way of telling the WHO why we claim the right to boss them around - in the nicest way, of course with DIPLOMACY and HONOR!

PART 2: WE JUST SENT A HUGE LEGAL PACKET TO THE WHO WITH A LEGAL DEADLINE OF 10 BUSINESS DAYS TO RESPOND.

Below is the “stakeholders engagement packet” section that we sent the WHO because usually an organization that invites stakeholders makes one… The WHO unsurprisingly forgot to make a “stakeholders engagement packet” for us, so we made one for them.

Albeit a bit unusual to make the stakeholders themselves do this task, it seems quite important, so we did the WHO’s job for them.

This is a long explanatory post - we will post in 6 parts to explain what we just sent and exactly what it means is currently legally in process as of today between IOJ team and the WHO:

1. IOJ Open Letter with links to the full packet and Rebuttals, which is what we sent the WHO today, May 2, 2022. Read Here:

2. Stakeholder engagement packet - Memorandum of Understanding of stakeholder engagement (very interesting to know our POWER) YOU ARE HERE

3. Rebuttal to Tedros opening remark Public Hearings.

4. Rebuttal to Tedros closing statement Public Hearings. Read Here > (COMING SOON)

5. Memorandum of Understanding regarding Human rights and health Duties of the WHO Read Here > (COMING SOON)

6. Costa Rica’s unresponsive health system under the WHO. Read Here > (COMING SOON)

We are pretty sure only the intellectuals and freedom fighters that want to take effective sustained action will care to read all the parts to our Open Letter to the WHO, but for them.. these posts should be pure GOLD!

Here is our epic stakeholders engagement packet that the WHO was definitely not expecting:

To: Kennith Piercy, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Soumya Swaminathan

This is our certified Stakeholder Engagement Packet and Memorandum of Understanding. It is an action of friendly diplomacy and introduction to our role as primary ‘key players’ representing a vulnerable class that is affected by the WHO pandemic preparedness and response policies.

Notification of Inadequate Mechanism to Participate

We are very glad to be in contact with you directly as the head of legal for WHO. We would like to extend a warm greeting and introduce WHO to Interest of Justice institute (IOJ) and our mission of probity in the public function through this open presentation of our stakeholder engagement packet.

Thank you for taking the time to send us the email April 12, 2022 informing us that stakeholders such as Interest of Justice are allotted only 2 minutes to speak once, as cause to deny our second attempt to place our input on the record in the public hearing. While we are very grateful to be recognized as stakeholders and sincerely appreciate being called in Session 1, two minutes was woefully inadequate for us to share our information and requirements as far as substantive elements and international human rights norms in a pandemic treaty.

We are happy that the WHO chose us as a “relevant” and “interested” stakeholder, which they say in this context includes non-State actors with a demonstrable interest in pandemic preparedness and responses, such as: international organizations; civil society organizations; private sector organizations; philanthropic organizations; scientific, medical and public policy institutions; academic institutions; and other such entities that have relevant knowledge, experience and/or expertise related to pandemic preparedness and response to share.

The word relevant is defined by Blacks Law dictionary as: Applying to the matter in question; affording something to the purpose. Iu Scotch law, good in law, legally sufficient; as, a “relevant” plea or defuse.

The word interested means: LEGAL INTEREST: Something a law recognizes, as in an advantage, profit, right, or share. A legal title is an example.

Unfortunately, due to time constraints we were only able to briefly touch upon 10 issues in 2 minutes and were unable to exercise our right of participation to meaningfully state for the record our relevant knowledge, experience and/or expertise related to pandemic preparedness and response that we really wanted to share, not just with the INB, but with the world. As the only civics and law institution who’s mission is to create procedures to protect human rights that we are aware of, with a stake or interest in this matter, we understandably wanted to share lengthy discussions of human rights law and the limits of WHO's powers to begin a discourse and education campaign to satisfy public interest and WHO’s constitutional guarantee that “Informed opinion and active co-operation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of the health of the people.”

We are uniquely qualified to lead the discussion the people are asking for, due to our marginalized members, but WHO is failing to accommodate the discussion of legality and application of human rights to each small or huge issue proposed by the new treaty.

Whilst proclaiming "one health" and “A world Together” as a catch phrase of inclusion, the WHO is leaving out our role as a civil society group and quashing our purpose of existence which is to facilitate a procedure for the peoples education and discussion - a way to really participate in the design, implantation and final decisions of health policy that affects us and our members.

Democracy thrives in sunlight and good governance practices for such a potential undertaking by the WHO ethically requires an effort to provide the public law and civics education as well as ample time to create an educated populace that can weigh two sides and use free will to determine the best option for themselves.

This rushed process is a wild rush by the WHO to a finish line for a signed agreement, which is not yet proved to be necessary or to be firmly desired by the people, let alone even remotely understood as to the real purpose and its possible effect on the rights and interests of the users. We are not aware of any discussion for creating solutions for mitigation or prevention of abuse of power by the WHO, and we have many, many requirements if a new treaty were negotiated for it to be valid, such as the people must be able and competent to analyze each clause for concise agreed definitions in conformity with national definitions, and there would need to be agreed upon procedures for enforcing limitations of emergency powers, to ensure due process and not usurp sovereignty.

The WHO’s position on disallowing Interest of Justice another chance to be meaningfully heard would almost make sense if there was a bona fide shortage of speaking slots, however, it appears that without providing good cause, the WHO has decided to bar us and others who attempted to speak for longer than 2 minutes. This is a flat denial of our right as stakeholders to meaningfully participate. We kindly asked to speak in Session 2, was denied as you explained to us by email, then at the end of Session 2 we were dismayed when the WHO called for more comments, stopping early by proclaiming , “no one else wants to speak”. No motivation was given why we couldn't speak twice since there was clearly time and an open forum to speak. We are certain the WHO can afford to allow the other denied groups and stakeholders a chance to speak by hosting longer sessions or more days of hearings.

We conclude the current participation process is lacking adequate stakeholder engagement and accountability mechanisms.

There is an apparent acceleration and undue rush by the WHO towards INB deliberations without allowing full public debate and presentation of facts about what should even be included or excluded, or if the treaty is even necessary, we wish to point out the participation process lacks substantive elements of due process.

The public interest is not served by this process that gives PPP’s an overwhelming majority at the table whilst at the same time it stymies our attempts at meaningful dialogue.

Substantive elements require consensus on all definitions first and foremost, then we need to discuss what is important to whom and why, in an open forum and in a human rights context.

The participation process is legally insufficient by not providing the public legal, factual and ethical information or a way to challenge arbitrary definitions. These challenges to WHO’s infallibility is required by law for WHO to meet its burden of motivation and substantiation for each decision which will ultimately affect every man and woman on earth.

The Public Hearing falls short of the definition of “stakeholder participation or engagement”

It cannot be overstated how legally insufficient the WHO’s current procedure is under the Costa Rican right to participate, because a mere single 2 minute chance to voice one way information by a minority of vulnerable marginalized stakeholders such as ourselves, is not the same as OECD defines as “participation”. Costa Rica is an OECD member and a proud “open government”. Only 38 countries have agreed to open government worldwide, but Costa Rica is one of them. As a civil society research institute we have an interest in our role in the open governance system and how to craft and create policy that will eventually be adopted by Costa Rica at every step.

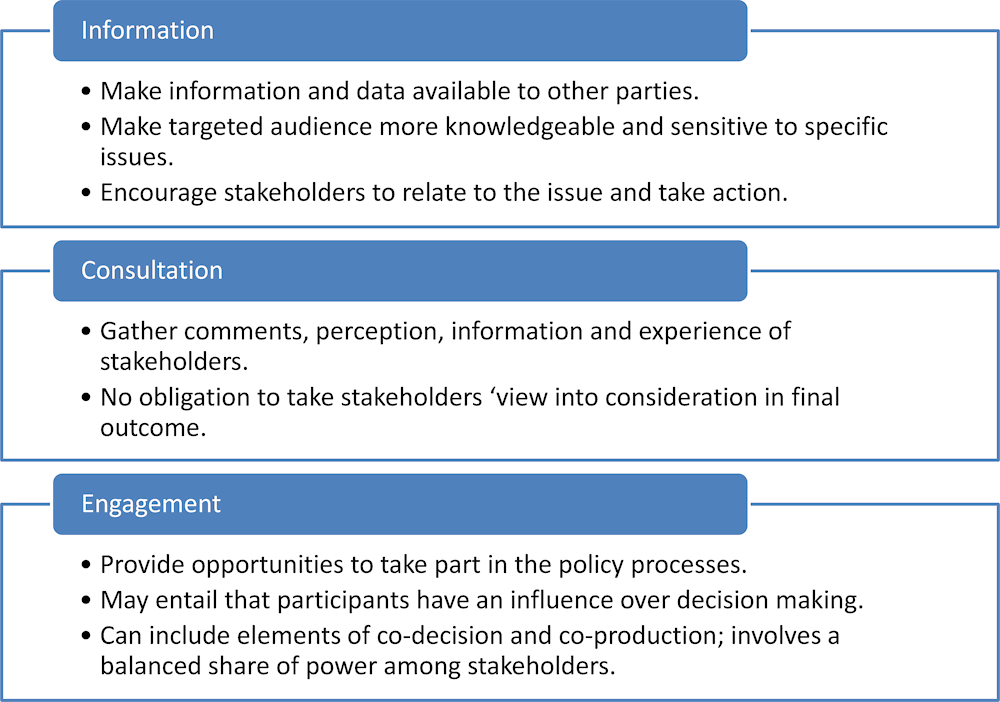

Open government implies three different but complementary and increasing levels of citizen-government relationships (Figure 1.1)

Information is a one-way relationship in which governments produce and deliver information to be used by citizens. It covers both “passive” access to information upon citizen demand and “active” measures by government to disseminate information to citizens. Examples include access to public records, official gazettes and government websites. Access to information is part of the legal frameworks of most countries today. It is an important precondition for citizens’ abilities to enquire, scrutinize and contribute to decision making (Gavelin, Burall and Wilson, 2009) and a key building block of open government reforms.

Costa Rica’s Law on Access to Information sets standards for all public bodies for disclosing government information and ensuring the availability of public data. It also specifies the obligation to respond to citizens’ requests for information. The law applies to bodies and institutions of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of state power, as well as local administration. Any other state-affiliated institutions as well as quasi-state sectors and de facto public officials of the WHO are also subject to the law. The WHO must follow the requirements to disclose information about their constitution, their activities and their results as a de facto public health agency and agents.

Access to information is a necessary, but on its own, insufficient precondition for effective citizen participation, as the provision of information does not automatically lead to participation. It is the attributes of the information disclosed, including its relevance to the concerns of stakeholders and its usability, that make the difference in the actual use of information for engagement and influencing policy decisions (OECD, 2016).

Figure 1.1. Levers of stakeholder participation

Source: OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Consultation is a two-way relationship in which citizens provide feedback to government (comments, perceptions, information, advice, experiences and ideas). It is based on the prior definition by government of the issues on which citizens’ views are being sought that require provision of information. Governments define the issues for consultation, set the questions and manage the process, while citizens are invited to contribute their views and opinions. The process is often initiated by decision makers looking for insights and views from stakeholders involved or who will likely be affected by the outcomes (OECD, 2016).

Some 94% of OECD countries require public consultation on some or all primary laws (OECD, 2015), and Costa Rica is included.

The WHO’s public Hearing is not participation, as one can easily see, its mere insufficient “consultation”.

Engagement or active participation in Costa Rica’s open government system is a relationship based on a partnership between citizens and governments. Citizens actively engage in defining the process and content of policy-making. Like consultation, engagement is based on a two-way interaction. It acknowledges equal standing for citizens in setting the agenda, proposing policy options and shaping the policy dialogue, although the responsibility for the final decision or policy formulation rests with the government in many instances (OECD, 2016).

Engagement recognizes the capacity of citizens to discuss and generate policy options in collaboration with the government. It requires governments to design their agendas with citizens and relies on governments’ commitment that policy proposals generated jointly will have an impact on the policy cycle (Corella, 2011). At the same time, engagement requires citizens to accept their increased responsibility for policy making. Engagement practices need to provide sufficient time and flexibility to allow for the emergence of new ideas and proposals by citizens, as well as mechanisms for their integration into government policy-making processes.

Nowadays, countries are increasingly exploring methods of actively engaging citizens in creating policies and co-designing and co-delivering services and the WHO should be no exception if they wish a role in the global governance of health.

The activities of public councils and committees in initiating and conducting public monitoring of services is a good example of citizen engagement in the evaluation and monitoring of government activities with the aim of improving service quality and user-centric delivery. If WHO is serious about improving service quality of health goods, then they need to allow sufficient time and not rush such an important process as a globally binding emergency treaty, especially when it has long been observed by the American Association for the International Commission of Jurists (AAICJ) that one of the main instruments employed by governments to repress and deny the fundamental rights and freedoms of peoples has been the illegal and unwarranted Declaration of Martial Law or a State of Emergency. Very often these measures are taken under the pretext of the existence of a “public emergency which threatens the life of the nation” or “threats to its national security.”

The abuse of applicable provisions allowing governments to limit and derogate from certain rights contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights has resulted in the need for a closer examination of the conditions and grounds for permissible limitations and derogations in order to achieve an effective implementation of the rule of law. The United Nations General Assembly has frequently emphasized the importance of a uniform interpretation of limitations on rights enunciated in the Covenant.

Accountability is an interactive process that requires that those held accountable explain their decisions and actions, and that defines the external stakeholders’ right and ability to inquire about those actions (Fox, 2014).

We claim the legal right to an interactive process of accountability with the WHO in order to fulfill our interests.

LEGAL RIGHT: the term given to a right or privilege that if challenged is supported in court.

Throughout this report, the analysis and recommendations target the goal of ensuring that this CIVICS AND LAW TREATY MONITORING COMMITTEE can effectively perform their role of promoting citizen’s active participation.

Enablers of citizen participation

Governments are responsible for encouraging citizens and stakeholder participation by creating an enabling environment and establishing appropriate legal, policy and institutional frameworks to help remove obstacles for the participation of everyone, and especially of those who are frequently excluded, for example youth, women or marginalised groups of society (OECD, 2017b).

The following analysis and recommendations are structured into four aspects that constitute the main enablers for stakeholders’ participation (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Enablers for participation

- Policy framework, including open government, anti-corruption, or digital government strategies

- Legal framework, including regulations and administrative procedures;

- Institutional framework, including financial and human resources, and related institutions to support participation practice;

- Capacity, i.e. the awareness, motivation and skills of policy-makers such as elected officials and civil servants to conduct participatory processes.

To create a shift towards participatory culture in policy-making, best practices from OECD countries suggest adopting a holistic approach by addressing all the above-mentioned enabling factors. Focusing on one component only, e.g. by merely adopting regulation but not supporting its implementation by building capacities, does not enhance participation. Furthermore, political and cultural attitudes are also part of creating a favorable environment for effective participation.

Under Costa Rica’s constitution Article 9 and Health Law Article 169 we have the right and duty to collaborate with health authorities in a participatory and collaborative process that involves vulnerable, marginalized primary stakeholders such as Interest of Justice in the design, implementation and final health policy decisions.

WHO claims to be the supreme global health authority and intends to create the treaty as a potentially binding negotiation, which will be a wholly illegitimate process without the ability of Interest of Justice to impart and receive information (due process) on all topics which may eventually become a health policy adopted by Costa Rica.

Interest of Justice is a primary stakeholder as defined by WHO. Please see:

“Stakeholder consultation has become a requirement in the successful development of public policy and service. Stakeholder consultation involves the development of constructive, productive relationships over the long term. It results in a relationship of mutual benefit. Not all stakeholders have the same importance and necessary involvement in the formation, development and evaluation of health policies.

An initial distinction can be made between:

•A primary stakeholder [such as Interest of Justice] is one who, without continuing participation, the policy or issue could not succeed or be addressed.

•A secondary stakeholder is one who has some influence or is affected by the policy or issue. However, their engagement is not essential to address the issue or to take policy action.

Interest of Justice represents the diffuse interests of the Disadvantaged or vulnerable, which according to World Bank, refers to those who may be more likely to be adversely affected by the project impacts and/or more limited than others in their ability to take advantage of a project’s benefits. Such an individual/group is also more likely to be excluded from/unable to participate fully in the mainstream consultation process and as such may require specific measures and/ or assistance to do so. This will take into account considerations relating to age, including the elderly and minors, and including in circumstances where they may be separated from their family, the community or other individuals upon which they depend.

Engaging in Meaningful Participation is defined by the WHO:

In principal, WHO concedes a government’s engagement with external stakeholders increases accountability to its citizens and is an indicator of good governance.

There are also practical policy benefits, such as:

•Assessing support and opposition to a policy;

•Giving government activities visibility and legitimacy;

•Empowering the marginalized;

•Increasing collaboration and the more efficient use of resources; and

•Ensuring the sustainability of interventions.

Overall, decision-making throughout the policy cycle will be more informed and in tune with those who the actions will affect. Through the engagement process, differing viewpoints will have been taken into account and so there should be an understanding of differing perspectives and that there may be a need for compromise.

Any refusal to provide an agreed upon mechanism for ongoing meaningful engagement with Interest of Justice and our vulnerable stakeholder groups would perceived as an unwillingness of WHO to compromise in ways that bolster private funders interests and harms public health for us marginalized stakeholders. We are truly interested primary stakeholders, with issues that cant be addressed without our participation and due process; compromise and robust discussion of human rights and control of legality is critical in this situation.

Governments under the direction of the WHO are responsible for the health of their peoples and have a critical leadership and stewardship role in the organized effort by society to promote health and well-being. However, the social determinants of health imply that many non-government stakeholders such as Interest of Justice have an interest or concern in health.

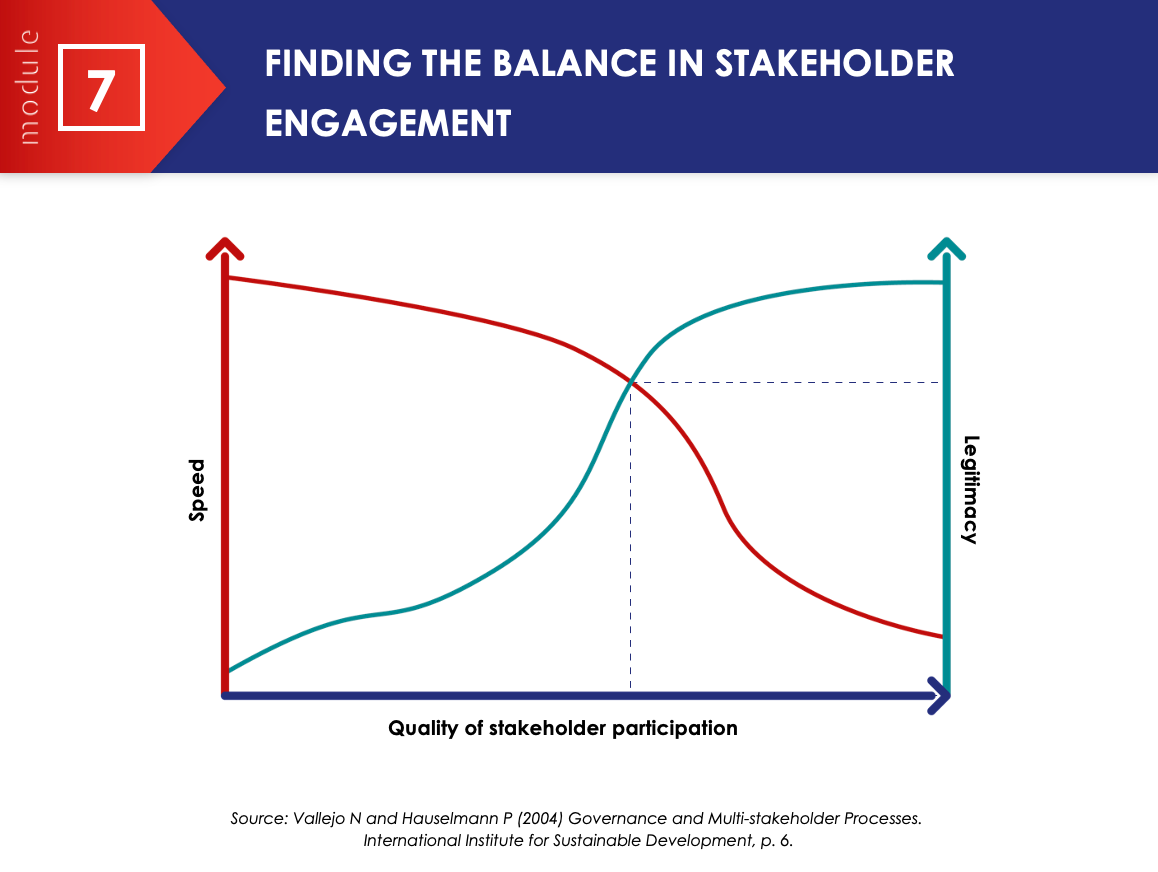

Speed vs Legitimacy

Parallel to the above-mentioned benefits, there are also challenges.

A comprehensive multi-stakeholder process can give high legitimacy to an initiative, but it also entails significant transaction costs. The more stakeholders at the table, the more difficult and time-consuming the process can be to reach a common understanding and position.

Some of the challenges or risks of stakeholder engagement can include:

- Prolonging policy-making;

- Increasing costs of intervention;

- Polarizing interest groups; and

- Creating unmanageable expectations.

One of the balances to find in consulting with external actors is between speed and legitimacy; fewer actors make policy formulation and implementation faster but stakeholders may be reluctant to accept or support a policy in which they had no say or influence. This slide illustrates this point.

As we have discussed, stakeholder engagement is important for both value-based and instrumental reasons.

The WHO stakeholder engagement program explicitly states: Given the potential value of stakeholder engagement and the reputational risks and possibly long-term problems if done incorrectly, it is sensible to consider the following principles:

•Empowerment: Stakeholders should share the responsibility for making decisions and accountability for the impacts of such decisions. Engaging stakeholders is morally essential to respect the fundamental rights and dignity of affected groups. You should aim to promote an inclusive and diverse stakeholder engagement with a tailored approach by stakeholder. A participatory inclusive approach should underpin the engagement process, giving stakeholders formal roles in governance structures, where feasible and applicable. Stakeholder engagement engenders a sense of shared ownership.

•Accountability: Stakeholder engagement leads to more ownership over the issues, thus improving the quality of policy recommendations and increased stakeholders’ interest in the policy-making process. It also promotes rigour and a quality-base to the relevant stages of the policy cycle. Furthermore, good governance is required to provide clarity about stakeholder engagement roles and responsibilities and what is expected of people involved in the policy-making process.

•Transparency: Promote open and honest engagement and set clear expectations. Ensure communication with stakeholders is clear and tailored to their specific needs. Communicate information to stakeholders early in the decision-making process, in ways that are meaningful and accessible. There should always exist the opportunity for every stakeholder to express their opinions and provide inputs. Be clear about the outcomes you are hoping to achieve and the steps on the way. Transparency also builds trust.

•Cost-effectiveness: Engaging early can lead to savings of both time and money in the long-term.

•Resources: Stakeholder engagement promotes the efficient use of resources (shared resources). In addition, a wide range of knowledge and skills can contribute to the policy agenda.

Research shows health is currently controlled by ‘key private sector players’ (pharmaceuticals), unconstitutionally limiting freedom of choice and limiting access and approval of natural ordinary options required for full exercise of right to health.

A whole of society approach

WHO concedes the activities of certain private companies can cause considerable harm to human health. We all know which certain private companies are ‘key WHO players’ and a bit too big for their britches. Naming them is irrelevant to this discussion at this time, it is sufficient to point out that the WHO is clear “the activities of certain private companies can cause considerable harm to human health”. Governments, thus, have a crucial role to play in the HiAP approach by engaging stakeholders within and beyond government, all the way to ensuring the WHO prevent “the activities of certain private companies that can cause considerable harm to human health”. A whole of society approach refers to coordinated efforts to improve health by multiple stakeholders within and outside government that may also be from several sectors.

As the WHO Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World states, “An integrated policy approach within government and international organizations, as well as a commitment to working with civil society and the private sector and across settings, are essential if progress is to be made in addressing the determinants of health.” WHO (2005) Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World.

When engaging with private sector, public transparency and ability to know conflicts of interest is imperative, otherwise it is a potential threat that can cause considerable harm to human health”.

Engaging with supportive external stakeholders such as research institutions and non-government health organizations like Interest of Justice can also help accumulate evidence and public support for radical measures to improve population health and inequity. This can be especially important for health ministries with limited political influence and resources such as ours in Costa Rica. In addition, particular external stakeholders, such as health and community services NGOs, such as Interest of Justice often have public trust, which makes them a critical partner for addressing societal concerns.

Engaging in meaningful stakeholder consultation can also help to harness ‘windows of opportunity’ and to facilitate policy change. The acceleration of change by private sector is not usually in line with human rights norms and as such those windows of opportunity must include us vulnerable primary stakeholders and not just include “the activities of certain private companies that can cause considerable harm to human health”.

We offer our service and have decided to interposition as a partnership law and civics oversight body that ensures the WHO is not facilitating policy that allows the activities of certain private companies that can cause considerable harm to human health. WHO says having established partnerships already in existence can mean that when a policy window does open, the ‘key players’ are already at the table, thus supporting policy entrepreneurs to act rapidly before the policy window closes.

Interest of Justice is acting rapidly before the window of opportunity to meaningfully participate closes. The ‘key players’ at the WHO’s table so far have been overwhelmingly private sector and funders of the WHO, and people are widely concerned that the negotiating table at the WHO is not comprised of key members of vulnerable primary stakeholders who are actually affected by the policy changes and decisions. This is inequitable on its face for the WHO to cherrypick stakeholders for “key” positions in private meetings, whilst giving us a mere 2 minutes to speak on behalf of the many groups of primary stakeholders who will be affected by proposed changes and pandemic policy being created and negotiated without their input.

Finally, consulting with us marginalized and vulnerable primary stakeholders in the policy cycle is best practice. It represents good governance and transparency, demonstrates a desire to engage in meaningful two-way or multi-directional communication, and recognizes the important contribution stakeholders at all levels can make to future policy changes, which will directly or indirectly affect them.

Best Practice

According to the WHO ‘Best practice’ – demonstrates desire to engage in meaningful two-way/multi-directional communication, and recognizes the important contribution stakeholders at all levels can make to future policy changes.

The Public Hearing was not in conformity with the WHO's own standard for ‘best practice’.

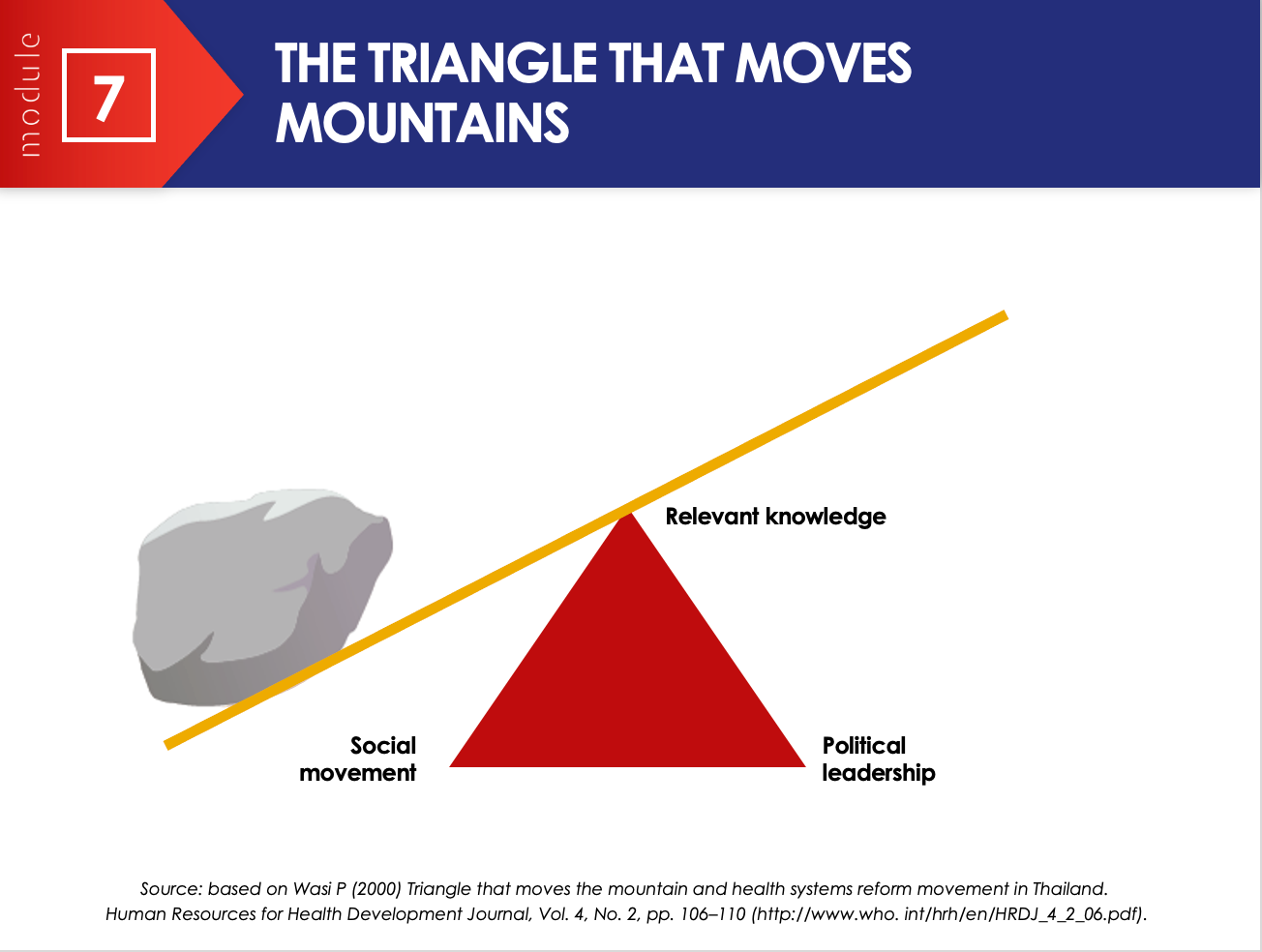

The combination of knowledge, social pressure and government leadership has been called the “triangle that moves mountains”. The Triangle aims to illustrate the power of evidence, civil movement and political leadership.

The Mountain means a big and very difficult problem, usually unmovable. The Triangle, as illustrated in this slide consists of: Creation of relevant knowledge through research, social movement or social learning and political involvement. Knowledge derived from research must be translated into forms and languages that can empower the public.

The “Triangle that Moves the Mountain” is a conceptualized strategy initiated as a social tool for solving difficult social problems, by simultaneously strengthening capacity in three interrelated areas: (1) creation of knowledge; (2) social movement; and (3) political involvement. The concept has been claimed as the basis of many successes in various Thai policy arenas.

The core principle that the triangle is underpinned by is to bring together the three areas (or groups) represented by the triangle corners to combine top-down and bottom-up approaches to achieve progress and reform. The triangular process aims to create synergy through the constant interaction and exposure between the three different areas (or groups) within a structured environment.

The power of various stakeholder groups coming together to complement each other is a huge strength in working collaboratively to co-design policy and its delivery strategies. It is unfair that private sector and privater foundations are ‘key players’ at the table while Interest of Justice are representing the human rights of those most affected and us primary stakeholders are marginalized to the point that serious legal and ethical topics are allotted a total 2 minutes.

Additional Country consideration:

In Costa Rica the WHO has installed actors into all health authorities and these actors all have direct or indirect ties to Bill Gates a multibillionaire vaccine investor and vaccine policy oversight. see: https://latribunacr.com/2021/12/27/quien-es-el-coordinador-y-secretario-tecnico-de-la-cnvi/ When the Administration was confronted that the vaccine commission head works for WHO and Bill Gates and is involved in vaccine policy directed by private sector with no way to assess and address conflicts of interest, the entire Health Ministry and Presidents office did nothing, referring the complaint back to the bad actor, in violation of duty of probity, despite all conflicted people needing to be removed under Costa Rica law. All of whom are in breach of duty for refusing to assess and address conflicts of interest affecting their impartiality and more criminal accusations arising from the mismanaged emergency responses.

Costa Rica’s President , Health Minister and Vaccination Commission Secretary have not disputed and are in DEFAULT on the following facts sent January 4th, 2021 and stamped “urgent” by the Health Ministry:

We also deposed the health minister Daniel and his administration about everyone who was a conflict of interest. Daniel once again defaulted and is disobedient, refusing to give adequate and truthful information about who works inside or outside of the administration on the pandemic response, who hired them, when were they hired and their conflicts of interests, as well as who chose the PCR test at 45ct which creates 100% false positives.

The fact that Daniels primary advisor on vaccines is Roberto Eduardo Arroba Tijerino who has many documented and serious conflicts of interests and he made an extrajudicial confession that NITAG [a WHO program] is “balancing independence from government and integration of NITAG decisions into government policy”, and in the same meeting he confessed: “There are currently no processes in place to assess and address conflicts of interest of members, but these are being developed”. You have a duty to cease and desist the use of the COVID-19 [non] vaccines recommended by the highly conflicted Roberto Eduardo Arroba Tijerino because the use of the gene based [non] vaccines in humans is premature and reckless, constituting human experimentation in violation of Nuremburg code 3, like us and 122 world’s top experts have warned you before in Amparo Expediente # 21-016342-0007-CO which was granted admissible with place in our favor by the Constitutional chamber in the Supreme court of Costa Rica for violating our rights.

Furthermore, vaccines as defined by the WHO (covid-19 “vaccine”) is not the same subject matter as a vaccine as defined by our legislature in Article 1 of the vaccination law. Clearly the two definitions conflict, and therefore we conclude that you incorporating the product called “covid- 19 vaccine” is treasonous, because it usurps the sovereignty of Costa Rica by supplanting our legislature’s definition and intent with the private health monopoly the WHO’s decisions, relying on their foreign and private definitions and intent, working in tandem with Roberto Eduardo Arroba Tijerino, the treasonous bad actor, and NITAG to “balance independence from government and integration of NITAG decisions into government policy.” The policy is illegal usurpation of Costa Rica sovereignty. For all these reasons, please IMMEDIATELY cease and desist the use of your dangerous product called covid-19 vaccines in humans.

POLITICAL INTERFERENCE IN THE SCIENTIFIC AND PUBLIC POLICY MAKING PROCESS AND THE WHO’S MANY CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This is an unacceptable breach of duty, caused by undue WHO interference in the scientific and public policy process causing imbalance affecting the political independence or the territorial integrity of the State or the existence or basic functioning of institutions indispensable to ensure and project the rights recognized in the ICCPR.

The fact the actors who came into office in Costa Rica’s Health Ministry overwhelmingly all work in lockstep to violate human rights, commit fraud, hide each others wrongdoing and insist WHO’s emails are private, while they all have ties to WHO is alarming and must be changed immediately to ensure the political and scientific independence of Costa Rica.

The WHO’s PAHO branch has recruited and hired the old Health Minister, Daniel Salas as Head of Immunization in Washington DC, who quit Friday April 29, a week early to join PAHO April 16, 2022. This shows PAHO is not able to critically assess the morality and legality of their recruits because Daniel Salas is guilty of violating the law under 21 U.S. Code § 360bbb–3 (e), and many national health and ethics laws as well as criminal laws when he mandated the covid-19 vaccine to health and government workers, and even a 6 year old against his pregnant mothers will, despite testifying its unapproved and under EUA. These crimes are accomplished by the men with interests in the WHO, Daniel Salas and Roberto Arroba Tijerino committing fraud on the court to our Supreme Court by testifying the vaccine is:

1. a vaccine, but only under the more broad definition of the WHO

2. Biontech was approved August 21, 2021 (later testifying its not, and even later contradicting prior testimony by stating Biontech is approved for over 16, which is also false)

3. The vaccine is safe and effective just like any other FDA approved vaccine

4. Not experimental (but later the vaccine commission confessed its investigational and unapproved) and Daniel Salas still lies to the court its not experimental

It is very concerning that the WHO is involved in hiring these men to manage vaccine recommendations to the country, who are in clear criminal violation of Federal EUA law, to manage vaccines and these men, using WHO’s definitions, have incorporated an investigational product into long term legislation to gain power not conferred by law.

The WHO and PAHO are acting in an irresponsible manner because despite knowing Daniel Salas has mandated an EUA experimental product, a clear breach of law, the WHO condones this, presumably because PAHO themselves are head of the WHO branch promoting needless Human Research on Children under flimsy excuses that if challenged do not hold up under strict scrutiny and the application of human rights norms. This research holds NO benefit for children, none. But research on children is very profitable for WHO’s funders who want to develop the gene technology for profit and accelerate the normal scientific process, thus violating the unequivocal rules of science and Costa Ricas General Law of Public Administration Article 16 acts must meet rules of science to be valid.

Costa Rica has a lot of corruption. Strikingly, under the PAHO the corruption was so insidious, Costa Rica’s highest court was defrauded into allowing State Sponsored terrorism and human research without informed consent, condoned by, promoted and requested by PAHO, using WHO’s spurious definitions of vaccine that conflict with local legislation. There are structural deficiencies within the WHO and PAHO that are now installed into Costa Rica’s system and its destroying democracy and the democratic functioning by the whole lot obstructing, delaying and hindering information and truth, to promote WHO’s agendas, presumably for the WHO’s funders interests at the expense of rule of law and human rights.

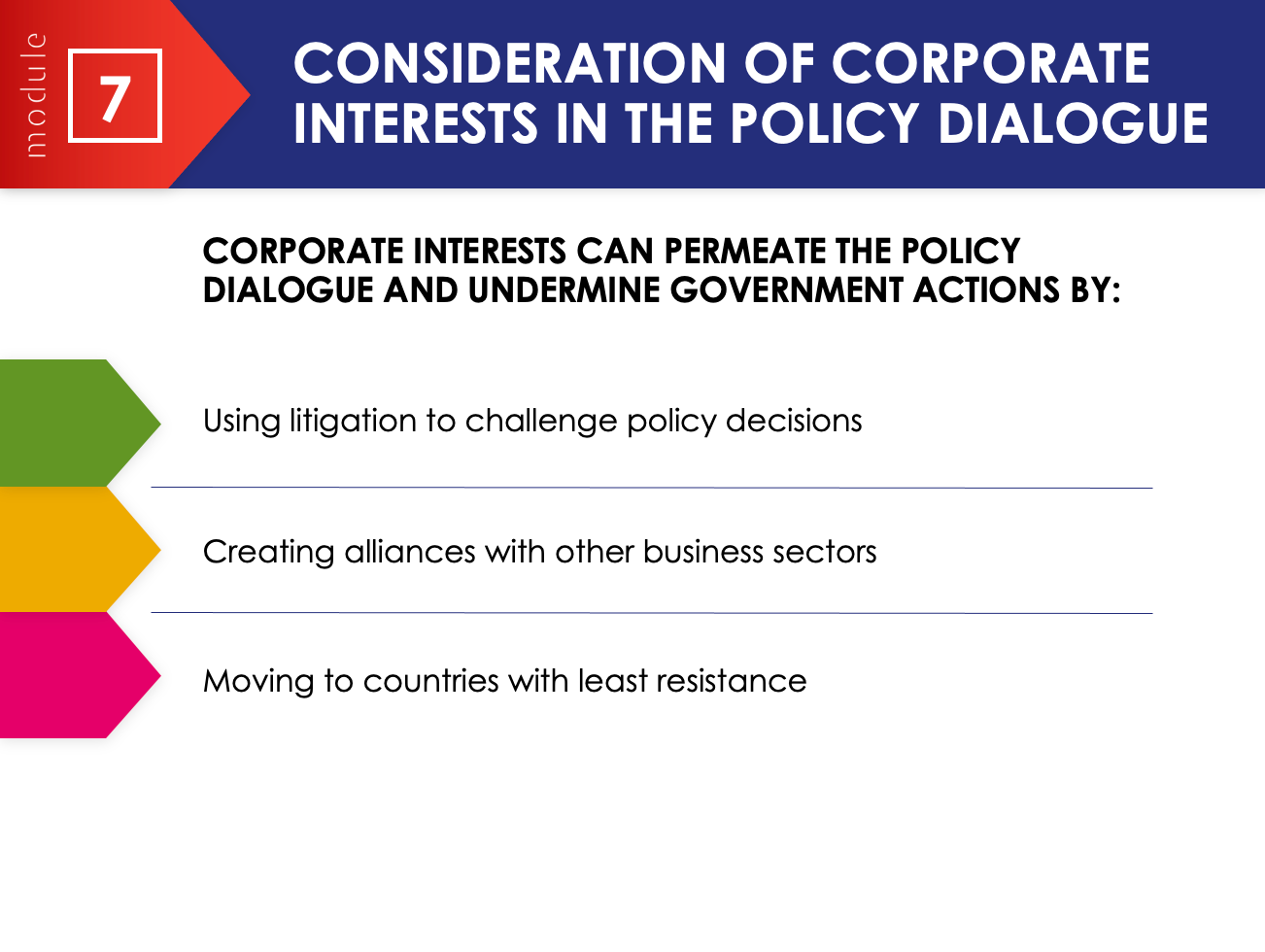

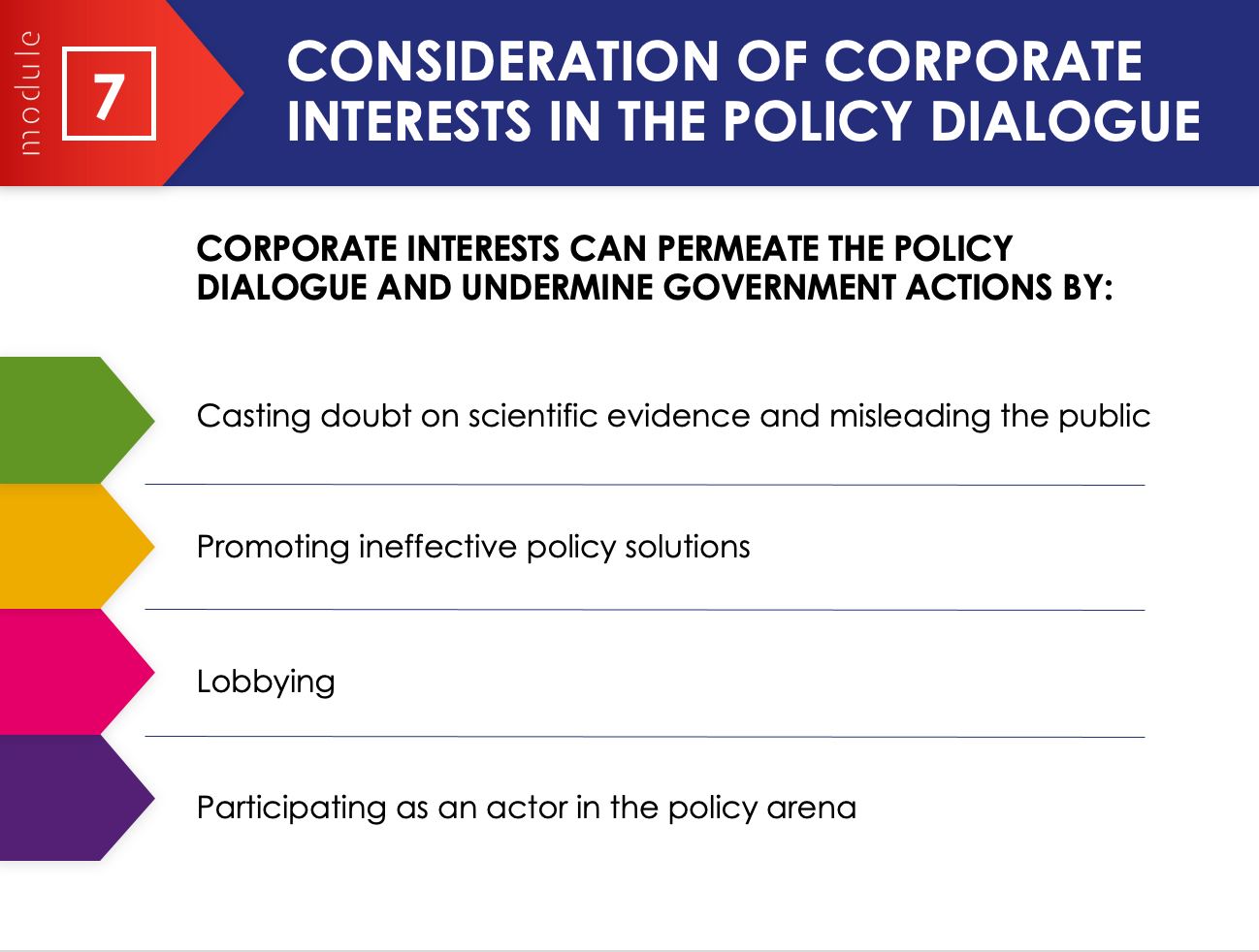

This slide outlines some of the ways in which corporate interests can be powerful in permeating the policy dialogue and undermine government actions.

This slide prepares participants for the next report – Negotiating for Health. It is, therefore, useful to ask participants to start to think about the different interests and strategies that may come into play during the negotiating process. Many of these tactics will come up again as common negotiation strategies, for example, avoidance, which is often used by actors seeking to stop or reduce the impact of state regulation, and avoidance is a rampant problem in Costa Rica and the world.

Corporate interests can undermine government actions in the policy process by:

Using litigation at national and international levels to challenge policy decisions.

Creating alliances with other business sectors for example, hospitality, gambling, biotechnology and surveillance, retail and advertising in the case of the tobacco and private-public partnerships involving full control of AI and media in the vaccine industry.

Creating alliances with other business sectors for example corporate media, big pharma, big tech, social media, AI, bio-surveillance above and below the skin, genetic and cellular editing, combination products, and government disinformation governing boards to create propaganda, spin the narrative, persecute the critics of corporate and public-private interests, even censoring and de-platforming free speech that conflicts with WHO’s “evolving” and often mistaken science is an international security threat that the WHO facilitates, requests, promotes with zeal; all of which is an apparatus that does not fulfill the WHO’s constitutional mission of articulating ethical and evidence-based policy options (while censoring experts evidence) and negates the purpose of the WHO, because it is a syndicate of corporate interests working in lockstep, which is extremely powerful in permeating and narrating the policy dialogue which is currently undermining government actions across the globe by violating every human right guarantee in a coordinated way that the average government and people are defenseless.

Moving to overly compliant desperate countries with least resistance such as Costa Rica. Markets are dynamic so regulatory efforts in one country can lead to expanding markets in others. Actors can accept decreases in one region as long as overall consumption of harmful products increases. For example, reductions in North American or some European markets may be compensated for by aggressive marketing elsewhere.

Public key decision makers can work in WHO bodies such as NITAG to “balance independence from government and integration of NITAG decisions into government policy.” in closed meetings with Pharmaceutical companies, where they are on public record bragging “There are currently no processes in place to assess and address conflicts of interest of members, but these are being developed”. As a result of no accountability the WHO and their funders are able to balance independence from government and integration of NITAG decisions into government policy, despite the integration of NITAG decisions actually conflicting with the national vaccination regulatory law 32722 Article 1 (p) definition of vaccine and other regulatory provisions, which outlines some of the ways in which both the WHO and their funders and partners corporate interests can be powerful in permeating the policy dialogue and undermine government actions, all with the approval, knowledge and consent of the WHO in their NITAG program, and service relationship, knowing Costa Rica has no way of assessing and addressing conflicts of interest.

To support the creation of positive economic/commercial determinants for health and health equity, the following should be considered:

•Produce balanced sectoral reports that consider actions to promote a responsible private sector

•Conduct and provide evidence and tools for health equity impact assessments of trade, investment, fiscal and monetary policies

•Define models for ethical investment that increase health equity

•Mobilize resources and capacities for health equity impact assessments of trade/fiscal/economic policies through building-up a community of practice across academia and NGOs

•Improve policy coherence across all sectors.

Developing non communicable disease (NCD) responses will require action across all government departments, as well the engagement of civil society and the private sector. Implementing a Health in All Policies, whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach for addressing NCDs is particularly useful when the people and censored experts are involved rather than marginalized and unable to contribute their expertise and knowledge.

Strong governance and regulatory frameworks to support multisectoral action on NCDs are a prerequisite for:

•Protecting the development of NCD policies from undue influence by any real, perceived or potential conflict of interest, including between the pharmaceutical, biosurveillance, AI, tobacco industry and public health; and

•Mobilizing adequate and sustained resources to implement NCD responses from public resources, non conflicted private business and finance, civil society organizations, and international development cooperation, including voluntary innovative financing mechanisms.

IOJ CIVIL SOCIETY RESEARCH FOR ACCOUNTABILITY AND EQUITY

Interest of Justice is a research institute who’s purpose is to defend human rights through the creation of regulations and procedures where there are gaps in the law and no way to claim the rights owed to the people. This letter itself is research into how to work with the WHO and not against, in order to ensure there are limitations to the WHO and governments ability to declare an emergency and limit rights.

Looking at the contribution of civil society to HiAP, or the whole-of-society approach, it is important to reiterate that civil society is a broad term that can encompass many actors including non-government organizations, faith-based groups, philanthropic foundations, labour unions, professional associations, cooperatives and research institutes. The single characteristic that these actors share is that they are not-for-profit.

PRIVATE SECTOR AS DEFINED BY THE WHO REQUIRES OVERSIGHT!

The next few slides are also created by the WHO and are intended to explore engagement with the private sector, particularly in regards to the commercial determinants of health, a subject we spoke of in the Public Hearing but could not elaborate upon due to time constraints imposed by the WHO. We are interested in the control of legality and probity in the private sector which can include multinational companies, micro, small and medium enterprises, individual entrepreneurs and financial intermediaries, and includes WHO’s funders acting as a majority of stakeholders, which may constitute conflicts of interests.

WHO concedes in these slides “that unlike civil society, the characteristic that the private sector ultimately shares is the pursuit of profit.”

The WHO is very clear that this “motivation and purpose for existing creates a complicated, often conflictual relationship with the public health sector given the principles of health as a matter of social justice and a public good.”

While on the one hand, the private sector might have considerable resources, expertise and technology to potentially direct towards public health, there are numerous issues such as neglected diseases, regulatory capture, conflicting social and eugenics ideology, and the commercial determinants of health that should suggest skepticism and caution.

Economic/corporate interests have an important role in shaping population health and redefining and limiting or expanding health equity, for example through trade and globalization.

Interest of Justice agrees emphatically with the WHO that “Private sector influence has risen exponentially with an increase in large private foundations and public–private partnerships. Particularly, in relation to the commercial determinants of health, changes in global business and consumption landscapes have boosted the power of large companies, with economic globalization and trade liberalization spurring the rapid expansion and corporate influence of these companies around the world. This perpetuates concerns about the role, effect and lack of accountability of private foundations when thinking about the private sector as a stakeholder in the policy-making process".”

Interest of Justice stands for millions of people voicing valid concerns about the role, effect and lack of accountability of private foundations when thinking about the private sector as a stakeholder in the policy-making process, such as GAVI, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust and Public-Private partnerships such as WEF who joined with WHO in 2017 according to the following tweet by Tedros.

Interest of Justice refers the WHO to THE SENATE PROOF ADJOURNMENT World Economic Forum SPEECH Tuesday, 29 March 2022 BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE, which must be refuted point by point with evidence, otherwise it will considered as a fact:

“Founded in 1971 by Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum is steeped in authoritarianism and Marxist ideology. It's an ideology which is creeping into governments across the world. When speaking about the Canadian parliament, Schwab himself said: 'We penetrate the cabinets. I know that half this cabinet—even more than half—are actually young global leaders of the World Economic Forum. It's true in Argentina, it's true in France—now with the President, who is a young global leader.' The World Economic Forum promotes globalist issues such as climate change, so-called systemic racism and sexism and creating an online digital identity. However, closer inspection reveals that the World Economic Forum is an anticapitalist and anti free market organisation that seeks to subvert Western values and political processes. They are very organised and very well funded. Their message is designed to appear harmless when, in fact, the ideology that underpins it is revolutionary and destructive. They train aspirational leaders in their ideology and help them make connections in spheres that include politics, business and the arts. The World Economic Forum has consistently advocated for the harshest and most extreme COVID measures possible, including lockdowns, mandatory vaccinations, vaccine passports and mask mandates, despite these policies assaulting many of our basic liberties. At the centre of the World Economic Forum's ideology is stakeholder capitalism. Essentially, this is a theory that traditional free market capitalism ignores the dangers posed by climate change, so the government must enforce restrictive policies to save the environment, even if that means less wealth. Why, then, are the forum's criticisms of capitalism always directed at Western nations, rather than the great polluters such as China and India? The forum believes that your freedoms should be minimised to prevent the imminent climate catastrophe—the one that has been coming for 10 years and the last 50 years, by the way. The central theme of the World Economic Forum's material is what they call the 'great reset', which is Klaus Schwab's term for the opportunity the pandemic has presented to reimagine and reinvent the economic policies of the West. The term comes directly from Schwab himself with his 2020 book entitled COVID-19: T he Great Reset. In a now-deleted video titled '8 predictions for the world in 2030', the World Economic Forum claimed, 'You'll own nothing and you'll be happy'—a slogan that hits the same dystopian note as 'Work makes you free' and 'Ignorance is strength'. You don't have to be a political philosopher to figure out that, if you own nothing, the state owns everything. There's a word for this: it's 'communism'. The World Economic Forum and its affiliates shamelessly promote the abolition of private property—a central facet of Karl Marx's demented utopian ideology which led to the deaths of tens of millions of people worldwide in the 20th century. To quote Margaret Thatcher: 'Communism never sleeps, never changes its objectives. Nor should we.' No matter how sophisticated the World Economic Forum tries to make the abolition of private property around the world sound, the fantasies of Karl Marx always lead to the crushing of individuals' liberties and lives and the expansion of the state's tyranny and power. It is imperative that we pay close attention to the World Economic Forum and do all that we can to preserve liberty and reduce government intrusion in our lives. If we fail to do so, the antidemocratic forces in the West will continue to march on, and we may wake up to an Australia that we no longer recognise. Australians deserve to know the extent of the World Economic Forum's influence and infiltration of our country, and we're going to find out.” *end*

Globalization is antithetical to nationalism, which is the legal order at present. Globalists act contrary to current law, slowly changing it through clever clauses in treaties and policy influence.

This WEF-UN-WHO partnership powered by huge multinational private stakeholders all working to establish Agenda 2030 SDG, whilst simultaneously espousing communist philosophies that “By 2030 You will own NOTHING and be happy” is antithetical to the concept of a free republic or democratic republic such as Costa Rica, therefore the alliance of WHO and WEF and public-private partnerships in the policy creation of regulations, definitions and even treaties, which has been a common penetration tactic of communists into the cabinets of free democracies to restrict liberty and free speech is unacceptable.

This tactic of communists using treaties to undermine government interests was known at least as far back as the 1950’s, and raises even more concerns today in this rushed and contested treaty process, considering the WEF’s involvement with the WHO and their purpose of abolition of privacy and property, which violates the human rights treaties signed by Costa Rica and the world, combined with near limitless power due to the concentration of private sector and private foundation stakeholders and their ties with government policy making:

There is a historical cause for concern about treaty making and good cause to invoke the duty of accountability:

"This Senate attitude hasn't been overlooked by crafty men who would stoop to any device to get their thoughts and ideas inflicted on the Nation and made the supreme law of the land. When men like Alger Hiss and other Communist and Socialist sympathizers wormed their way into positions of great influence in the State Department and took over the job of drafting up our treaties and agreements with international organizations some rather strange and dangerous clauses began to crop up in these documents. These clauses for the most part went unnoticed by Senators who seldom have either the time or the inclination to wade through voluminous treaty agreements prior to voting on them. But other people were perfectly aware of these clauses. They knew full well that treaties automatically become the supreme law of the land upon ratification and thus take precedence over the Federal Constitution and all our State laws." (Congressional Record, 1953, page A422) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1953-pt9/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1953-pt9-1.pdf

U.N.’s documented history of unbroken communism raises concerns, especially in context of Agenda 2030, with the WEF’s threat of the abolition of privacy and property rights by 2030, a communist ideology inherent within U.N.

"Now let us look at the record. According to Trygve Lie, longtime Secretary General of the United Nations, he stated flatly that there was a secret agreement between Alger Hiss and Molotov to the effect that the head of the United Nations military staff should always be a Communist. That agreement has never been broken, and we have had a succession of Communists filling that post, the present one being Mr. Arkadov. As a first consequence of this treasonous agreement, this country lost its first military engagement in Korea at a cost to this country of more than $20 billion and 145,000 American casualties ...This was the first war in which we engaged not as the United States military force, but as a United Nations force. ...How convenient this was to the Communists to have one of their own men as head of the United Nations military staff, who reviewed all orders going from the Pentagon to General MacArthur and gave them to our enemy before General MacArthur received them."(Congressional Record, 1962, page 215) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt1/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1962-pt1-3-2.pdf

The WHO concedes:

"evidence suggests that fit-for-purpose regulatory regimes are needed to constrain negative corporate influences on health and to encourage ethical business practices beneficial for population health.”

There is a need to encourage positive economic determinants of health.

We will now explore the issue of government stakeholder engagement with the private sector in relation to the commercial determinants of health.

According to Kickbusch I, Allen L & Franz C (2016). The commercial determinants of health. The Lancet Global Health; 4(12), PE895-E896 the WHO defines the commercial determinants of health as “strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health”.

Transnational food companies powerfully shape the supply, demand, and consumption of food and beverage products. These companies are one of the main drivers of the increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and sugary beverages, which are cheap, highly palatable, and sold in large portion sizes, but which are also high in energy and fat, salt and/or sugar. Furthermore, transnational companies are moving quickly into markets in developing countries, where regulation may be less stringent, and aggressive marketing strategies can be deployed. This has led to a ‘nutrition transition’ in many developing countries, i.e. a move away from healthier traditional diets, to ‘westernized’ diets higher in fat, salt and sugar. Increasing consumption of products such as fast food and sugar –sweetened beverages is in turn linked to rising levels of obesity and diabetes.

The global food industry also has a significant influence on policy and regulation that aims to improve nutrition and diet-related health. The food industry often plays a key role in international and national policy-making, including through processes of consultation with government. It increasingly engages in collaborative initiatives with government (and non-government) actors that have obesity prevention objectives, as with Australia’s ‘Health Star’ interpretive food labelling system.

However, the industry also lobbies against global and national initiatives that it sees as compromising its economic interests, raising a possibility of detrimental effects on laws and policies aimed at improving diet-related health. Accordingly, whether to engage the food industry in obesity prevention efforts and on the commercial determinants of health (and how to do so effectively) is a matter of considerable debate (and research) within the public health community.

At the same time there is an overwhelming involvement of the WHO and their Pharmaceutical investor funders moving quickly into markets in developing countries such as Costa Rica, where regulation may be less stringent, and aggressive marketing strategies can be deployed through exerting external control of Costa Ricas overly compliant and conflicted Health Authorities, such as gene or cell editing or gene therapy ‘covid-19 vaccines’, and programs that “balance independence from government and integration of NITAG (and other WHO and corporate bodies that lobby) decisions into government policy.”

WHO concedes “it is not sufficient to ignore the private sector, or to give it inappropriate roles in policy development.”

WHO believes that engagement with private-sector agents is necessary, especially when addressing the wider determinants of health. Interest of Justice concedes this may be true, but engagement by funders must be open, transparent and accountable to the people who are the end users and consumers, especially so when they claim their rights are being affected by the public-private policy making.

Prior to 1948, the WHO could accept donations only from member states. In 2005 at the time of creating the IHR they changed their policies to also allow for private funding. Today, only 20% of its funding comes from member states, with the other 80% from private sources, including pharmaceutical companies.

Thirteen percent of the WHO’s funding ($300 million annually) comes from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—a larger contribution than the United States government. Bill Gates is alleged by a WHO whistleblower to have a seat on the ex officio WHO board with sovereignty and full immunity for GAVI and himself. Bill Gates admits he earned billions in profits from the vaccines, which proves GAVI is profiting from the policies made by Bill Gates and other pharmaceutical investing funders of the WHO. The WHO’s list of donors includes AstraZeneca, Bayer, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Merck, which are also stakeholders in WEF and the public-private partnership with WHO. This is causing serious structural defects in the integrity of the WHO, and as Margaret Chan confessed candidly, if this problem isn’t prevented the WHO will not be as great as they were”

In practice, real or perceived differences in understanding and motivation between reform leaders in government, on the one hand, and private-sector interests, on the other, are often a critical barrier that has to be tackled in developing policy change focusing on the public/private mix. Government is often stereotyped as being explicitly and exclusively concerned with the public interest, in contrast to private agents who are seen as only self-interested and profit hungry. That perceived divide might encourage reform leaders and policy-makers simply to ignore the private sector, or to give it inappropriate roles in policy development, such as seats at the table that create policy inherent with serious imbalances of power detrimental to health.

WHO tells us stakeholders that “the degree to which interests converge or overlap is, therefore, a foundation for further action.”

It will fundamentally shape the type of public/private interaction on health policy issues. Building up a careful understanding of the range of interests of the private sector will be an important basis for strategic action. To do this, it must not only be understood that private-sector interests are often heterogeneous, but that in some cases one actor may hold multiple objectives. WHO delves further into this discussion when we look at Module 8 – Negotiating for Health (not in this presentation)

In addressing public/private mix issues, it will be particularly important to see what private-sector actors can bring to the policy development process – whether it be information and technical skills to help make decisions, or power or resources to allow for smooth implementation of policy.

At the same time, the government, WHO and this CIVICS AND LAW MONITORING COMMITTEE clearly needs to manage the less desirable features that the private sector may bring to policy development. Chief among these, especially in the for-profit sector, is divergent interests that conflict with and are adverse to the interests of those WHO seeks to serve.

It is well settled that interactions between government(s) and the private sector need to be guided by public interest and transparency currently nonexistent within the WHO “accountability” framework.

The concept of public-private partnerships and their role in building healthy public policy, giving an example of how WHO claims private interests have been managed successfully.

A PPP is defined by Reich (see reference above) as:

1. The collaborations should involve at least one public organization and one private profit-making organization. The WHO claims public organization could include national government bodies and international agencies such as the WHO, World Bank or a United Nations agency. The “private sector” normally would extend to any type of profit-making corporation.

2. The partners are mistakenly presumed by the WHO that they will have certain common goals for a particular health problem, but at the same time WHO conceeds there may be ulterior motives that .

3. The different partners will divide the workload and mutually receive benefits.

This slide outlines some of the ways in which corporate interests can be powerful in permeating the policy dialogue and undermine government actions. This slide prepares participants for the next lecture – Negotiating for Health. It is, therefore, useful to ask participants to start to think about the different interests and strategies that may come into play during the negotiating process. Many of these tactics will come up again as common negotiation strategies, for example, avoidance, which is often used by actors seeking to stop or reduce the impact of state regulation.

Corporate interests can undermine government actions in the policy process by:

Casting doubt on scientific evidence and misleading the public by denying negative health effects.

Using globally controlled corporate media to mislead the entire world into unnecessary and even dangerous uptake of certain products

creating false data by misusing modeling techniques

hiding trial safety data

censoring and financially destroying critics with proof of fraud or safety signals that may interrupt sales

Promoting ineffective policy solutions. For example, the alcohol industry has promoted corporate social responsibility, a policy intervention that has been proven to be ineffective as the incentives favour irresponsibility rather than responsibility.

Permeating and, at times, infiltrating other sectors or decision-making levels by lobbying policy-makers and politicians or recruiting former civil servants with credibility among their peers. Pharmaceutical lobbyists even end up with secret contracts that are unconstitutional, but profitable. Pharmaceutical and Tobacco lobbyists might also reach other sectors (e.g. trying to persuade policy-makers of benefits for tobacco growers’ livelihoods or of potential revenue losses following a tax increase) and ultimately permeate their political discourse.

Participating as an actor in the policy arena. Engagement can be negative and, even where positive, is often limited or superficial.

INVOKE Right to Participation

As a result of us being aware of our rights and duties, and desiring to exercise those rights in a way that is meaningful to us and our growing body of stakeholder members, we hereby INVOKE our right under Costa Ricas Constitution Article 9 to be intimately involved in the entire process of any policy making that may eventually be adopted by Costa Rica. According to the WHO in their slideshow called stakeholders engagement, “Non-governmental stakeholders usually play critical roles in the policy formation and development stages of the policy cycle, however, the engagement of non-government stakeholders can play a role at all stages of the policy cycle.”

THE PURPOSE AND METHOD OF PARTICIPATION: The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health extended participation under the right to health, recognising that “[t]he right to health requires that health policies, programmes and projects are participatory. The active and informed participation of all stakeholders can broaden consensus and a sense of ‘ownership’, promote collaboration and increase the chances of success” (Hunt & Bueno de Mesquita 2006). WHO has drawn from this rights-based consensus to find that “[t]he principle of participation and inclusion means that people are entitled to participate in decisions that directly affect them, such as the design, implementation and monitoring of health interventions. Participation should be active, free and meaningful**”** (WHO, 2011).

THE REALITY: WHO identifies participation of those affected by policies, laws, and decisions as one of the five key elements of pandemic governance, especially relevant for preparedness governance, as it serves an important opportunity to secure participation which may not be possible during a pandemic response. Yet, participation of affected communities has been a critical omission in the development of the WHO’s mission to “develop the research agenda”, and in country preparedness plans and national task forces. The majority of people who are supposed to be served and health enhanced by the services offered by the WHO are systematically injured by being denied equal treatment due to blanket medical recommendations, lack of freedom of choice, adequate and truthful information, protection of their basic safety and financial interests and administrative participation in health decisions.

We need more information. In fact we just need some information

The WHO Secretariat is seeking input from all interested parties in these hearings, and strongly encourages participation in this important process.

The WHO Constitution provides that, “Informed opinion and active co-operation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of the health of the people.”

The INB Public Hearings: The World Together, and public interest and support in them, helps to advance this critical principle.

"As noted in the eighth preambular paragraph of the WHO Constitution, “Informed opinion and active co-operation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of the health of the people.”

This is problematic that a new binding treaty is being created without the Informed opinion and active co-operation on the part of the public. For instance, we are kept in the dark about the results of the INB's first deliberation in August 2021.

What was decided?

When do we get notice and the ability to respond (due process)?

The following list are the essential elements of real and meaningful participation to us in this process that WHO defines as “historic”, urging us all “strongly” to participate.

WHO is recommended to:

1. Provide a more detailed explanation that gives us ADEQUATE AND TRUTHFUL INFORMATION & due process to accept or rebut the WHO’s reason for the necessity of a new pandemic treaty. What is missing out of the preexisting international instruments? Why does WHO need to create this new treaty? What is the benefit and risks of a binding treaty?

2. Provide the strict scrutiny compelling public interest test, and who was involved?

3. Provide the cost benefit analysis in detail, with any data sets or modeling to review, if relied upon, and who is involved in the cost benefit analysis?

4. We have a very long list of questions that require information on motivation and substantiation in the design process of the treaty that would not be information commonly available by FOIA request. Who do we send the questions to, and is there any reason why the CR deadline of 10 business days to respond would not apply to the WHO?

5. Involve the LAW AND CIVICS TREATY MONITORING COMMITTEE step by step, in a fully transparent online forum, to bring the voice of the marginalized and our long list of legal concerns to the table to be heard and meaningfully addressed by the INB, who has a duty to substantiate their decisions and allow for challenge to ethical and legal concerns in a series of interim public hearings. This will increase legitimacy, even if it takes longer, due to the accommodation of more viewpoints.

6. This inclusion of primary stakeholders who are affected by the policies will allow for a more robust discussion of the legal, ethical and HiAP agendas promoted by WHO, but little is known by the public due to WHO’s lack of visibly promoted information.

7. This inclusion of primary stakeholders who are affected by the policies will allow for the Collaboration is at the heart of all we do. From governments and civil society to international organizations, foundations, advocates, researchers and health workers – we mobilize every part of society to advance the health and security of all.

The Costa Rican Constitutional Court has noted previously that Ordinal 30 of the Political Constitution guarantees free access to the "administrative departments for purposes of information on matters of public interest", a fundamental right that in the doctrine has been called the right of access to administrative files and records, however, the most accurate denomination is the right of access to administrative information, since, the access to the material or virtual supports of the public administrations is the instrument or mechanism to reach the proposed purpose that consists in that the administered ones impose themselves of the information held by them. It is necessary to indicate that not always the administrative information of public interest sought by an administered is found in a file, archive or administrative record. The right of access to administrative information is a mechanism of control in the hands of the public administrations, since it allows them to exercise an optimal control of the legality and the opportunity, convenience or merit and, in general, of the effectiveness and efficiency of the administrative function performed by the different public entities. Efficient and effective public administrations are those that are subject to public control and scrutiny, but there can be no citizen control without adequate information. Thus, a logical link can be established between access to administrative information, knowledge and management of this information, effective or timely citizen control and efficient public administrations. The right of access to administrative information is deeply rooted in a series of principles and values inherent to the Social and Democratic Rule of Law, which, at the same time, acts. Thus, effective and direct citizen participation in the management and handling of public affairs is inconceivable without a significant amount of information about administrative competencies and services, in the same way, the democratic principle is strengthened when the various social, economic and political forces and groups participate actively and informedly in the formation and execution of the public will. Finally, the right of access to administrative information is an indispensable tool, like so many others, for the full validity of the principles of administrative transparency and publicity.”

CERTIFICATION OF INTEREST OF JUSTICE’S TEN PRIMARY STAKEHOLDER INTERESTS:

Interest of Justice raised 10 points at the public hearing that demonstrate our standing as primary stakeholders “who, without continuing participation, the policy or issue could not succeed or be addressed”, which we summarize as follows :

"We request the following:

All technical recommendations and limitations to rights in an emergency shall conform to the requirements set in the Siracusa Principles.

No treaty can be binding which confers upon the WHO the power to issue or enforce pandemic guidance which may supplant the nations constitution, written definitions and sovereign legislation.

Persecution and censorship of diversity of opinion regarding WHO’s “evolving science” is expressly prohibited; free and open discourse shall be protected and encouraged in the public interest to prevent imbalance of power and systematic violations of human rights

The centralization of national health data, gene and biotechnology, AI with Big Tech and media, poses an international security threat that must be prevented at all costs.

Pre-determination and punishment of misinformation with no written law defining misinformation backed by science and due process, is prohibited by law and punishable.

The WHO shall not exaggerate the seriousness of the diagnosis, complicate the treatment, or artificially create alarm situations in response to spurious interests; if found guilty the member states should agree to permanently stop all funding and relationships with the WHO, in the public interest

The WHO must immediately declare all yearly funders with full transparency and allow for independent oversight with the ability to immediately remove all conflicts of interest

The Member States require WHO agrees to be liable in the event that damages arise from the use of the guidance

The final decision in a truly democratic process, should be made by the people rather than the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body which may be widely perceived as biased and usurping individual and national sovereignty.

Procedures for meaningful participation by all people in the enforcement of human rights enshrined in Siracusa Principles shall be made readily available in all future WHO pandemic guidance"

Interest in National Sovereignty Requires Strict Scrutiny and WHO to meet the Burden of Proof

Because the WHO’s attempt at a treaty is clearly an attempt to create policy, which is the realm of the sovereign legislator. Therefore, due to the extremely unusual position that WHO is declaring as global Health policy monopoly we require strict oversight and monitoring capability of the INB’s deliberations, by us and other marginalized primary stakeholders, in a process that allows for the time required to reach consensus with real meaningful due process, otherwise our association will be forced to reject the final document for failing to include us and our stakeholder members in the design and implementation of the ultimate global health policy/treaty.

It is also worth mentioning that in the event WHO decides to exclude us and our members in the INB deliberations and subsequently decide to create policy which caters to the majority of stakeholders wishes (which is biased and stacked towards ensuring a majority of stakeholder interests from the private sector and private foundations) please be advised we will be forced to decree the WHO’s participatory process illegitimate ab initio, wholly illusory and insufficient.

We hope we are mistaken, but on and for the record, we do presume the illegitimacy of the current WHO pandemic treaty process. We conclude the process does not withstand strict scrutiny of necessity, and constitutional limits, because this is an unprecedented health policy deliberation made not by the sovereign people and nations, it is by the WHO, a private body, funded by a majority of private-public interests, which unilaterally claims sovereignty and supreme power of health policy decision making.

While the goal of the WHO may be noble in wanting to protect global health, our organization Interest of Justice alleges that a global binding pandemic treaty with enforcement power by WHO is a “violation of the legal principle” whereby “only through a formal law issued by the Legislature, according to the procedure established in the Constitution for the enactment of laws, is it possible to regulate and, if appropriate, restrict fundamental rights and freedoms.” This is very problematic and must be addressed by WHO, otherwise the WHO may proceed in ways that could incur prohibition, if not liability for usurpation of sovereignty, a problem raised by nations repeatedly over the WHO’s history.