NO NEED TO REPORT "ANTICIPATED" ADVERSE EFFECTS? Including death! Is This Why Slide 16 Was Made? They Got Free Pass To NOT Report Stroke, Death? Outrageous US "Research Protections" Laws Must Change

This is horrible law: Read the free pass to murder and maim: "Reviewing and Reporting Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks to Subjects or Others and Adverse Events: OHRP Guidance (2007)" Yikes!

This is a very long post below because we think some of you will want to read the entire document Reviewing and Reporting Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks to Subjects or Others and Adverse Events: OHRP Guidance (2007) and study all of our highlights and arrows pointing out key issues with the mRNA genetic therapy called “COVID-19 (non) “vaccines”

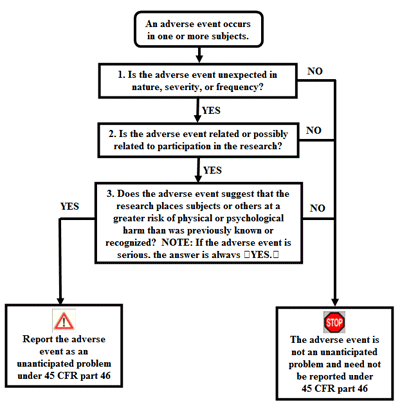

This is about a critical issue of US law where we learned that only unexpected adverse effects need be reported. Yes you read that right.

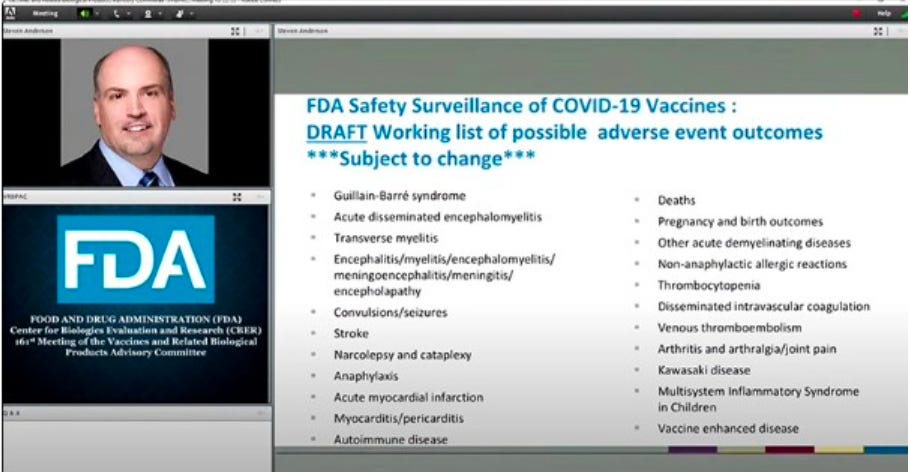

Is this why FDA made slides of the anticipated 22 serious effects, including stroke and death, then preauthorized the rollout as if those would not be serious adverse effects as compared to covid? Looks like it.

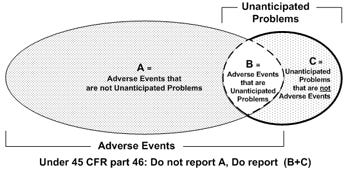

In particular, this guidance clarifies that only a small subset of adverse events occurring in human subjects participating in research are unanticipated problems that must be reported under 45 CFR part 46.

In OHRP’s experience the vast majority of adverse events occurring in the context of research are expected in light of:

(1) the known toxicities and side effects of the research procedures;

(2) the expected natural progression of subjects’ underlying diseases, disorders, and conditions; and

(3) subjects’ predisposing risk factor profiles for the adverse events. Thus, most individual adverse events do not meet the first criterion for an unanticipated problem and do not need to be reported under the HHS regulations 45 CFR part 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5) (see examples (1)-(4) in Appendix C).

This is HUGE because the FDA made slides with 22 expected serious adverse effects the FDA anticipated (and therefore need not report) - please learn and share!

Nuremberg Code was waived by this horrible law and we want everyone to realize the evil FDA scam!

Side note: Today is a day of remembrance and reverence for Nuremberg Code!

Today August 20, 2024 is the 77th Anniversary of Nuremberg Code.

We will be sending you a link to our new Justice For Humanity podcast later this afternoon August 20, 2024.

Join our Nuremberg Code Commemoration coming later today - Road to Nuremberg 2 Ep 2 with Dr. Yeadon, Dr. Janci Lindsay, Sasha Latypova and Interest of Justice co-founders Dustin Bryce and Lady Xylie.

We will discuss our love of ethics and celebrate the humanity of man to ever make the code in the first place, as well as deep dive into the regulatory and public health law problems, give our reactions and offer solutions as we briefly discuss our case for Crimes Against Humanity which is just beginning to take the first sworn depositions.

OHRP is the Office Human Research “Protections”. They don’t need to protect you from expected results… of death!??? They should but do not.

How do they get away with this? The experimenters at FDA simply compare risk of death from the allegedly dangerous covid threat to the vax in order to “balance” out their evil equation. This is to pretend death is not serious (covid was gonna kill you anyway right?) and therefore, even though death is serious, it does not need to be reported as “unexpected”. They expect death and pretend it’s not serious, yes, they pretend theres no greater risk of harm from the shots than from covid, and ta-da with that dirty trick up their sleeve the FDA does not mandate anyone report it.

They forgot Nuremberg Code!

So this is the scam?

Reporting of UNANTICIPATED adverse events has a protocol to report them and they are counted.

However,

ANTICIPATED results DO NOT NEED TO BE REPORTED… SO THEY ARE NOT EVEN COUNTED? WHAT THE HELL? Nuremberg Code!

Before going further let’s do a quick refresher so you will be able to read the long document Reviewing and Reporting Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks to Subjects or Others and Adverse Events: OHRP Guidance (2007) in context of what adverse effects were anticipated, and therefore FDA never needed to report.

Welcome to FDA, where we make slides of possible adverse outcomes that include death, stroke, myocarditis, etc, then we gaslight you and tell you horse paste and sun doesn’t work, take the safe and effective jab, then we here at FDA we stubbornly refuse to monitor the known risks we expose you to!

Anticipating DEATH

Authorizing DEATH

Hiding and not reporting DEATH…

No need to report anything the FDA can ANTICIPATE and downplay as “not serious”.

It’s not serious to DIE based on their presumption that the harm is not more serious than the harm we are already exposed to (with covid). Can you even believe how evil this is? It ensures flawed results in the trial that excludes all serious adverse effects (think of 12 year old Maddie) simply because they were anticipated serious side effects and because the harm was perceived as no more harm than we were already exposed to with such a horrible purported pandemic.

It is just outrageous the adverse effects which are anticipated do not get reported in trials or outside trials as a matter of law! We think people should be aware of this.

In our soon to be filed lawsuit (couple months) we allege FDA is violating Costa Rica’s import laws which offer more human rights protections and forbid serious undue experimentation. All support is needed and super appreciated to pay the Attorney fees to finish the last phase of work to file!

We are competent at law, but judging by the fact we are late on the Attorneys bills to start the depositions, apparently we are not very good fundraisers lol. We humbly ask everyone for help who can afford to donate, because this is not OUR case, it is a globally important case for humanity, perhaps THE most important.

The case that still needs community support will potentially implicate DoD, FDA & WHO (plus Big Pharma) in crimes against humanity, which is enforceable in Costa Rica’s Universal Jurisdiction. Thank you for considering the largest donation you can give as we are meeting the Attorneys and need to pay them a substantial amount we were unable to raise this month!

FDA sucks!!!! Public Health Law Abomination of a Corrupt Nation.

Learn more below how PAHO and WHO work with the FDA and military to waive all research standards and track expected outcomes (but the law allows the researchers and manufacturers to never report them).

Repeat: Slide 16 matters! Alert! Alert! Alert! What is the infamous FDA Slide 16? Is it evidence of KNOWLEDGE needed for a Crime Against Humanity?

The infamous slide 16, shows the FDA’s draft list of “possible adverse event outcomes,” which appeared briefly during a public meeting by the US Food and Drug Administration’s Product Advisory Committee on Oct, 22, 2020 reviewing the safety and efficacy of Covid-19 vaccines.

In this meeting the FDA decided to move from single individual use called expanded access use EAU to emergency use authorization EUA for masses, a dubious legal strategy which allowed them to skip basic research protections (that IOJ is challenging in our upcoming lawsuit).

While adverse events were generally discussed throughout the meeting, the slide’s contents were not covered in-depth. The meeting came as the FDA was considering granting emergency use authorization to Pfizer and Biontech’s experimental jab. Despite the long list of known possible side effects, the FDA later granted Pfizer emergency use authorization on December 11, 2020, about two months after the meeting.

During the same meeting, a similar list of adverse reactions also appeared briefly during deputy director of the Immunization Safety Office at the CDC Tom Shimabukuro’s presentation (at around 2:06:29 - see below)

In the same meeting at the beginning the FDA made false promises:

We here at the “reputable” FDA promised to monitor adverse effects in “near real time”, but sorry, we forgot to tell you we monitored mass death and murder then stopped monitoring altogether because we are like ostriches with our head in the sand.

Meet the VRBPAC members that tried to save humanity from FDA’s mass experimentation & were ignored:

Now there were VRBPAC members who expressed concerns that the standards we outlined were not sufficient. Some VRBPAC members expressed concerns that immediate follow-up of two months after completion of the vaccination regimen would not be sufficient to support an EUA for rapid and widespread deployment, in particular for vaccines manufactured using novel. Others raised a concern that a successful interim efficacy analysis, especially an early one with more limited COVID-19 cases and wider confidence intervals compared to a final analysis, would not be sufficient to support an EUA for rapid and widespread deployment.

The Mengele Mafia VRBPAC members & experimental “vaccine” peddlers won:

Other VRBPAC members, though, commented that two months median follow-up could be sufficient to support issuance of an EUA. And that evaluation for rare adverse events and waning protection could thus be accomplished by surveillance during the use under EUA.

Next slide, please.

(and off they went warp speed to the races)

In our soon to be filed lawsuit we allege FDA is violating Costa Rica’s import laws which offer more human rights protections and forbid serious undue experimentation. All support is needed and appreciated to pay the Attorney fees! Our Attorneys are asking us to pay them the monthly payments. We only need to raise $5000 this month to start the depositions for Crimes Against Humanity, which will go to ICC and the Costa Rica prosecutors who are working with us. We are asking readers for urgent help to pay and finish this important case with Dr. Yeadon, Dr. Janci Lindsay, Sasha Latypova and many other experts. Nuremberg Code Anniversary today should remind everyone that we really need to work hard to protect what ethical norms our forefathers fought so hard to give us. Let’s litigate - don’t hesitate!

The proof below - It’s long but worth the deep dive in your free time:

We made arrows and highlights through the text and images of the whole document below so most of you can skim and still catch the importance of this information.

Reviewing and Reporting Unanticipated Problems Involving Risks to Subjects or Others and Adverse Events: OHRP Guidance (2007)

This guidance represents OHRP's current thinking on this topic and should be viewed as recommendations unless specific regulatory requirements are cited. The use of the word must in OHRP guidance means that something is required under HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46. The use of the word should in OHRP guidance means that something is recommended or suggested, but not required. An institution may use an alternative approach if the approach satisfies the requirements of the HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46. OHRP is available to discuss alternative approaches at 240-453-6900 or 866-447-4777.

Date: January 15, 2007

Scope: This document applies to non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS.

It provides guidance on HHS regulations for the protection of human research subjects at 45 CFR part 46 related to the review and reporting of

(a) unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others (hereinafter referred to as unanticipated problems); and

(b) adverse events. In particular, this guidance clarifies that only a small subset of adverse events occurring in human subjects participating in research are unanticipated problems that must be reported under 45 CFR part 46.

The guidance is intended to help ensure that the review and reporting of unanticipated problems and adverse events occur in a timely, meaningful way so that human subjects can be better protected from avoidable harms while reducing unnecessary burden.

The guidance addresses the following topics:

I. What are unanticipated problems?

III. How do you determine which adverse events are unanticipated problems?

VI. What should the IRB consider at the time of initial review with respect to adverse events?

VIII. What should written IRB procedures include with respect to reporting unanticipated problems?

Appendices

Appendix A: Glossary of Key Terms

NOTE: For some HHS-conducted or -supported research, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the HHS agency conducting or supporting the research (e.g., the National Institutes of Health [NIH]) may have separate regulatory and policy requirements regarding the reporting of unanticipated problems and adverse events. Anyone needing guidance on the reporting requirements of FDA or other HHS agencies should contact these agencies directly.

Furthermore, investigators and IRBs should be cognizant of any applicable state and local laws and regulations related to unanticipated problems and adverse events experienced by research subjects, as well as foreign requirements for research conducted outside the United States. OHRP recommends that investigators and IRBs consult with their legal advisors for guidance regarding pertinent state, local, and international laws and regulations.

In our soon to be filed lawsuit we allege FDA is violating Costa Rica’s import laws which offer more human rights protections and forbid serious undue experimentation. All support is needed and appreciated to pay the Attorney fees!

Target Audience: IRBs, investigators, and HHS funding agencies that may be responsible for review, conduct, or oversight of human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS.

Regulatory Background:

HHS regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR part 46) contain five specific requirements relevant to the review and reporting of unanticipated problems and adverse events:

Institutions engaged in human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS must have written procedures for ensuring prompt reporting to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, and any supporting department or agency head of any unanticipated problem involving risks to subjects or others (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)).

For research covered by an assurance approved for federalwide use by OHRP, HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(a) require that institutions promptly report any unanticipated problems to OHRP.

In order to approve research conducted or supported by HHS, the IRB must determine, among other things, that:

Risks to subjects are minimized (i) by using procedures which are consistent with sound research design and which do not unnecessarily expose subjects to risk, and (ii) whenever appropriate, by using procedures already being performed on the subject for diagnostic or treatment purposes (45 CFR 46.111(a)(1)).

Risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits, if any, to the subjects, and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result (45 CFR 46.111(a)(2)).

When appropriate, the research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring the data collected to ensure the safety of subjects (45 CFR 46.111(a)(6)).

An IRB must conduct continuing review of research conducted or supported by HHS at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk, but not less than once per year, and shall have authority to observe or have a third party observe the consent process and the research (45 CFR 46.109(e)).

An IRB must have authority to suspend or terminate approval of research conducted or supported by HHS that is not being conducted in accordance with the IRB’s requirements or that has been associated with unexpected serious harm to subjects. Any suspension or termination of approval must include a statement of the reasons for the IRB’s action and must be reported promptly to the investigator, appropriate institutional officials, and any supporting department or agency head (45 CFR 46.113).

Guidance:

I. What are unanticipated problems?

The phrase “unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others” is found but not defined in the HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46. OHRP considers unanticipated problems, in general, to include any incident, experience, or outcome that meets all of the following criteria:

unexpected (in terms of nature, severity, or frequency) given (a) the research procedures that are described in the protocol-related documents, such as the IRB-approved research protocol and informed consent document; and (b) the characteristics of the subject population being studied;

related or possibly related to participation in the research (in this guidance document, possibly related means there is a reasonable possibility that the incident, experience, or outcome may have been caused by the procedures involved in the research); and

suggests that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of harm (including physical, psychological, economic, or social harm) than was previously known or recognized.

OHRP recognizes that it may be difficult to determine whether a particular incident, experience, or outcome is unexpected and whether it is related or possibly related to participation in the research. OHRP notes that an incident, experience, or outcome that meets the three criteria above generally will warrant consideration of substantive changes in the research protocol or informed consent process/document or other corrective actions in order to protect the safety, welfare, or rights of subjects or others. Examples of corrective actions or substantive changes that might need to be considered in response to an unanticipated problem include:

changes to the research protocol initiated by the investigator prior to obtaining IRB approval to eliminate apparent immediate hazards to subjects;

modification of inclusion or exclusion criteria to mitigate the newly identified risks;

implementation of additional procedures for monitoring subjects;

suspension of enrollment of new subjects;

suspension of research procedures in currently enrolled subjects;

modification of informed consent documents to include a description of newly recognized risks; and

provision of additional information about newly recognized risks to previously enrolled subjects.

As discussed in the sections II and III below, only a small subset of adverse events occurring in human subjects participating in research will meet these three criteria for an unanticipated problem.

Furthermore, there are other types of incidents, experiences, and outcomes that occur during the conduct of human subjects research that represent unanticipated problems but are not considered adverse events. For example, some unanticipated problems involve social or economic harm instead of the physical or psychological harm associated with adverse events. In other cases, unanticipated problems place subjects or others at increased risk of harm, but no harm occurs. Appendix B provides examples of unanticipated problems that do not involve adverse events but must be reported under the HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5).

The HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46 do not define or use the term adverse event, nor is there a common definition of this term across government and non-government entities. In this guidance document, the term adverse event in general is used very broadly and includes any event meeting the following definition:

Any untoward or unfavorable medical occurrence in a human subject, including any abnormal sign (for example, abnormal physical exam or laboratory finding), symptom, or disease, temporally associated with the subject’s participation in the research, whether or not considered related to the subject’s participation in the research (modified from the definition of adverse events in the 1996 International Conference on Harmonization E-6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice).

Adverse events encompass both physical and psychological harms. They occur most commonly in the context of biomedical research, although on occasion, they can occur in the context of social and behavioral research.

In the context of multicenter clinical trials, adverse events can be characterized as either internal adverse events or external adverse events. From the perspective of one particular institution engaged in a multicenter clinical trial, internal adverse events are those adverse events experienced by subjects enrolled by the investigator(s) at that institution, whereas external adverse events are those adverse events experienced by subjects enrolled by investigators at other institutions engaged in the clinical trial. In the context of a single-center clinical trial, all adverse events would be considered internal adverse events.

In the case of an internal adverse event at a particular institution, an investigator at that institution typically becomes aware of the event directly from the subject, another collaborating investigator at the same institution, or the subject’s healthcare provider. In the case of external adverse events, the investigators at all participating institutions learn of such events via reports that are distributed by the sponsor or coordinating center of the multicenter clinical trials. At many institutions, reports of external adverse events represent the majority of adverse event reports currently being submitted by investigators to IRBs.

III. How do you determine which adverse events are unanticipated problems?

In OHRP’s experience, most IRB members, investigators, and institutional officials understand the scope and meaning of the term adverse event in the research context, but lack a clear understanding of OHRP’s expectations for what, when, and to whom adverse events need to be reported as unanticipated problems, given the requirements of the HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46.

The following Venn diagram summarizes the general relationship between adverse events and unanticipated problems:

The diagram illustrates three key points:

The vast majority of adverse events occurring in human subjects are not unanticipated problems (area A).

A small proportion of adverse events are unanticipated problems (area B).

Unanticipated problems include other incidents, experiences, and outcomes that are not adverse events (area C).

The key question regarding a particular adverse event is whether it meets the three criteria described in section I and therefore represents an unanticipated problem. To determine whether an adverse event is an unanticipated problem, the following questions should be asked:

Is the adverse event unexpected?

Is the adverse event related or possibly related to participation in the research?

Does the adverse event suggest that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of harm than was previously known or recognized?

If the answer to all three questions is yes, then the adverse event is an unanticipated problem and must be reported to appropriate entities under the HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5). The next three sub-sections discuss the assessment of these three questions.

A. Assessing whether an adverse event is unexpected

In this guidance document, OHRP defines unexpected adverse event as follows:

Any adverse event occurring in one or more subjects participating in a research protocol, the nature, severity, or frequency of which is not consistent with either:

the known or foreseeable risk of adverse events associated with the procedures involved in the research that are described in (a) the protocol-related documents, such as the IRB-approved research protocol, any applicable investigator brochure, and the current IRB-approved informed consent document, and (b) other relevant sources of information, such as product labeling and package inserts; or

the expected natural progression of any underlying disease, disorder, or condition of the subject(s) experiencing the adverse event and the subject’s predisposing risk factor profile for the adverse event.

(Modified from the definition of unexpected adverse drug experience in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a).)

Examples of unexpected adverse events under this definition include the following:

liver failure due to diffuse hepatic necrosis occurring in a subject without any underlying liver disease would be an unexpected adverse event (by virtue of its unexpected nature) if the protocol-related documents and other relevant sources of information did not identify liver disease as a potential adverse event;

Hodgkin’s disease (HD) occurring in a subject without predisposing risk factors for HD would be an unexpected adverse event (by virtue of its unexpected nature) if the protocol-related documents and other relevant sources of information only referred to acute myelogenous leukemia as a potential adverse event; and

liver failure due to diffuse hepatic necrosis occurring in a subject without any underlying liver disease would be an unexpected adverse event (by virtue of its unexpected greater severity) if the protocol-related documents and other relevant sources of information only referred to elevated hepatic enzymes or hepatitis as potential adverse events related to the procedures involved in the research.

In comparison, prolonged severe neutropenia and opportunistic infections occurring in subjects administered an experimental chemotherapy regimen as part of an oncology clinical trial would be examples of expected adverse events if the protocol-related documents described prolonged severe neutropenia and opportunistic infections as common risks for all subjects.

OHRP recognizes that it may be difficult to determine whether a particular adverse event is unexpected. OHRP notes that for many studies, determining whether a particular adverse event is unexpected by virtue of an unexpectedly higher frequency can only be done through an analysis of appropriate data on all subjects enrolled in the research.

In OHRP’s experience the vast majority of adverse events occurring in the context of research are expected in light of:

(1) the known toxicities and side effects of the research procedures;

(2) the expected natural progression of subjects’ underlying diseases, disorders, and conditions; and

(3) subjects’ predisposing risk factor profiles for the adverse events. Thus, most individual adverse events do not meet the first criterion for an unanticipated problem and do not need to be reported under the HHS regulations 45 CFR part 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5) (see examples (1)-(4) in Appendix C).

B. Assessing whether an adverse event is related or possibly related to participation in research

Adverse events may be caused by one or more of the following:

the procedures involved in the research;

an underlying disease, disorder, or condition of the subject; or

other circumstances unrelated to either the research or any underlying disease, disorder, or condition of the subject.

In general, adverse events that are determined to be at least partially caused by (1) would be considered related to participation in the research, whereas adverse events determined to be solely caused by (2) or (3) would be considered unrelated to participation in the research.

For example, for subjects with cancer participating in oncology clinical trials testing chemotherapy drugs, neutropenia and anemia are common adverse events related to participation in the research. Likewise, if a subject with cancer and diabetes mellitus participates in an oncology clinical trial testing an investigational chemotherapy agent and experiences a severe hypoglycemia reaction that is determined to be caused by an interaction between the subject’s diabetes medication and the investigational chemotherapy agent, such a hypoglycemic reaction would be another example of an adverse event related to participation in the research.

In contrast, for subjects with cancer enrolled in a non-interventional, observational research registry study designed to collect longitudinal morbidity and mortality outcome data on the subjects, the death of a subject from progression of the cancer would be an adverse event that is related to the subject’s underlying disease and is unrelated to participation in the research. Finally, the death of a subject participating in the same cancer research registry study from being struck by a car while crossing the street would be an adverse event that is unrelated to both participation in the research and the subject’s underlying disease.

Determinations about the relatedness of adverse events to participation in research commonly result in probability statements that fall along a continuum between definitely related to the research and definitely unrelated to participation in the research. OHRP considers possibly related to participation in the research to be an important threshold for determining whether a particular adverse event represents an unanticipated problem. In this guidance document, OHRP defines possibly related as follows:

There is a reasonable possibility that the adverse event may have been caused by the procedures involved in the research (modified from the definition of associated with use of the drug in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a)).

OHRP recognizes that it may be difficult to determine whether a particular adverse event is related or possibly related to participation in the research.

Many individual adverse events occurring in the context of research are not related to participation in the research and, therefore, do not meet the second criterion for an unanticipated problem and do not need to be reported under the HHS regulations 45 CFR part 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5) (see examples (5) and (6) in Appendix C).

C. Assessing whether an adverse event suggests that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of harm than was previously known or recognized

The first step in assessing whether an adverse event meets the third criterion for an unanticipated problem is to determine whether the adverse event is serious.

In this guidance document, OHRP defines serious adverse event as any adverse event that:

results in death;

is life-threatening (places the subject at immediate risk of death from the event as it occurred);

results in inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization;

results in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity;

results in a congenital anomaly/birth defect; or

based upon appropriate medical judgment, may jeopardize the subject’s health and may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in this definition (examples of such events include allergic bronchospasm requiring intensive treatment in the emergency room or at home, blood dyscrasias or convulsions that do not result in inpatient hospitalization, or the development of drug dependency or drug abuse).

(Modified from the definition of serious adverse drug experience in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a).)

OHRP considers adverse events that are unexpected, related or possibly related to participation in research, and serious to be the most important subset of adverse events representing unanticipated problems because such events always suggest that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of physical or psychological harm than was previously known or recognized and routinely warrant consideration of substantive changes in the research protocol or informed consent process/document or other corrective actions in order to protect the safety, welfare, or rights of subjects (see examples (1)-(4) in section Appendix D).

Furthermore, OHRP notes that IRBs have authority to suspend or terminate approval of research that, among other things, has been associated with unexpected serious harm to subjects (45 CFR 46.113). In order for IRBs to exercise this important authority in a timely manner, they must be informed promptly of those adverse events that are unexpected, related or possibly related to participation in the research, and serious (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)).

However, other adverse events that are unexpected and related or possibly related to participation in the research, but not serious, would also be unanticipated problems if they suggest that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of physical or psychological harm than was previously known or recognized. Again, such events routinely warrant consideration of substantive changes in the research protocol or informed consent process/document or other corrective actions in order to protect the safety, welfare, or rights of subjects or others (see examples (5) and (6) in Appendix D).

KEY FACT - PAY ATTENTION FOLKS!

This is pretty crazy that anyone would ever trust FDA after reading their methodology:

The flow chart below provides an algorithm for determining whether an adverse event represents an unanticipated problem that needs to be reported under HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46.

A. Reporting of internal adverse events by investigators to IRBs

For an internal adverse event, a local investigator typically becomes aware of the event directly from the subject, another collaborating local investigator, or the subject’s healthcare provider.

Upon becoming aware of an internal adverse event, the investigator should assess whether the adverse event represents an unanticipated problem following the guidelines described in section III above. If the investigator determines that the adverse event represents an unanticipated problem, the investigator must report it promptly to the IRB (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)).

Regardless of whether the internal adverse event is determined to be an unanticipated problem, the investigator also must ensure that the adverse event is reported to a monitoring entity (e.g., the research sponsor, a coordinating or statistical center, an independent medical monitor, or a DSMB/DMC) if required under the monitoring provisions described in the IRB-approved protocol or by institutional policy.

If the investigator determines that an adverse event is not an unanticipated problem, but the monitoring entity subsequently determines that the adverse event does in fact represent an unanticipated problem (for example, due to an unexpectedly higher frequency of the event), the monitoring entity should report this determination to the investigator, and such reports must be promptly submitted by the investigator to the IRB (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)).

B. Reporting of external adverse events by investigators to IRBs

Investigators and IRBs at many institutions routinely receive a large volume of reports of external adverse events experienced by subjects enrolled in multicenter clinical trials. These external adverse event reports frequently represent the majority of adverse event reports submitted by investigators to IRBs. OHRP notes that reports of individual external adverse events often lack sufficient information to allow investigators or IRBs at each institution engaged in a multicenter clinical trial to make meaningful judgments about whether the adverse events are unexpected, are related or possibly related to participation in the research, or suggest that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of physical or psychological harm than was previously known or recognized.

OHRP advises that it is neither useful nor necessary under the HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46 for reports of individual adverse events occurring in subjects enrolled in multicenter studies to be distributed routinely to investigators or IRBs at all institutions conducting the research. Individual adverse events should only be reported to investigators and IRBs at all institutions when a determination has been made that the events meet the criteria for an unanticipated problem. In general, the investigators and IRBs at all these institutions are not appropriately situated to assess the significance of individual external adverse events. Ideally, adverse events occurring in subjects enrolled in a multicenter study should be submitted for review and analysis to a monitoring entity (e.g., the research sponsor, a coordinating or statistical center, or a DSMB/DMC) in accordance with a monitoring plan described in the IRB-approved protocol.

Only when a particular adverse event or series of adverse events is determined to meet the criteria for an unanticipated problem should a report of the adverse event(s) be submitted to the IRB at each institution under the HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46. Typically, such reports to the IRBs are submitted by investigators. OHRP recommends that any distributed reports include: (1) a clear explanation of why the adverse event or series of adverse events has been determined to be an unanticipated problem; and (2) a description of any proposed protocol changes or other corrective actions to be taken by the investigators in response to the unanticipated problem.

When an investigator receives a report of an external adverse event, the investigator should review the report and assess whether it identifies the adverse event as being:

unexpected;

related or possibly related to participation in the research; and

serious or otherwise one that suggests that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of physical or psychological harm than was previously known or recognized.

Only external adverse events that are identified in the report as meeting all three criteria must be reported promptly by the investigator to the IRB as unanticipated problems under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(b)(5). OHRP expects that individual external adverse events rarely will meet these criteria for an unanticipated problem.

C. Reporting of other unanticipated problems (not related to adverse events) by investigators to IRBs

Upon becoming aware of any other incident, experience, or outcome (not related to an adverse event; see Appendix B for examples) that may represent an unanticipated problem, the investigator should assess whether the incident, experience, or outcome represents an unanticipated problem by applying the criteria described in section I. If the investigator determines that the incident, experience, or outcome represents an unanticipated problem, the investigator must report it promptly to the IRB (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)).

D. Content of reports of unanticipated problems submitted to IRBs

OHRP recommends that investigators include the following information when reporting an adverse event, or any other incident, experience, or outcome as an unanticipated problem to the IRB:

appropriate identifying information for the research protocol, such as the title, investigator’s name, and the IRB project number;

a detailed description of the adverse event, incident, experience, or outcome;

an explanation of the basis for determining that the adverse event, incident, experience, or outcome represents an unanticipated problem; and

(4) a description of any changes to the protocol or other corrective actions that have been taken or are proposed in response to the unanticipated problem.

E. Changes to a multicenter research protocol that are proposed by an investigator at one institution in response to an unanticipated problem

For multicenter research protocols, if a local investigator at one institution engaged in the research independently proposes changes to the protocol or informed consent document in response to an unanticipated problem, the investigator should consult with the study sponsor or coordinating center regarding the proposed changes because changes at one site could have significant implications for the entire research study.

F. IRB review and further reporting of unanticipated problems

Once reported to the IRB, further review and reporting of any unanticipated problems must proceed in accordance with the institution’s written procedures for reporting unanticipated problems, as required by HHS regulations at 45 CRF 46.103(b)(5). The HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46 do not specify requirements for how such unanticipated problems are reviewed by the IRB. Therefore, IRBs are free to implement a wide range of procedures for reviewing unanticipated problems, including review by the IRB chairperson or another IRB member, a subcommittee of the IRB, or the convened IRB, among others. When reviewing a report of an unanticipated problem, the IRB should consider whether the affected research protocol still satisfies the requirements for IRB approval under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.111. In particular, the IRB should consider whether risks to subjects are still minimized and reasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits, if any, to the subjects and the importance of the knowledge that may reasonably be expected to result.

When reviewing a particular incident, experience, or outcome reported as an unanticipated problem by the investigator, the IRB may determine that the incident, experience, or outcome does not meet all three criteria for an unanticipated problem. In such cases, further reporting to appropriate institutional officials, the department or agency head (or designee), and OHRP would not be required under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5).

The IRB has authority, under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.109(a), to require, as a condition of continued approval by the IRB, submission of more detailed information by the investigator(s), the sponsor, the study coordinating center, or DSMB/DMC about any adverse event or unanticipated problem occurring in a research protocol.

Any proposed changes to a research study in response to an unanticipated problem must be reviewed and approved by the IRB before being implemented, except when necessary to eliminate apparent immediate hazards to subjects. If the changes are more than minor, the changes must be reviewed and approved by the convened IRB (45 CFR 46.103(b)(4) and 46.110(a)). OHRP recommends that for multicenter research protocols, if the IRB proposes changes to the protocol or informed consent documents/process in addition to those proposed by the study sponsor, coordinating center, or local investigator, the IRB should request in writing that the local investigator discuss the proposed modifications with the study sponsor or coordinating center and submit a response or necessary modifications for review by the IRB.

Institutions must have written procedures for reporting unanticipated problems to appropriate institutional officials (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)). The regulations do not specify who the appropriate institutional officials are. Institutions may develop written procedures that specify different institutional officials as being appropriate for different types of unanticipated problems. For example, an institution could develop written procedures designating the IRB chairperson and members as the only appropriate institutional officials to whom external adverse events that are unanticipated problems are to be reported, and designating the Vice President for Research as an additional appropriate institutional official to whom internal adverse events that are unanticipated problems are to be reported by the IRB chairperson.

G. Reporting unanticipated problems to OHRP and supporting agency heads (or designees)

Unanticipated problems occurring in research covered by an OHRP-approved assurance also must be reported by the institution to the supporting HHS agency head (or designee) and OHRP (45 CFR 46.103(a)). Typically, the IRB chairperson or administrator, or another appropriate institutional official identified under the institution’s written IRB procedures, is responsible for reporting unanticipated problems to the supporting HHS agency head (or designee) and OHRP. For further information on reporting to OHRP, see the Guidance on Reporting Incidents to OHRP.

For multicenter research projects, only the institution at which the subject(s) experienced an adverse event determined to be an unanticipated problem (or the institution at which any other type of unanticipated problem occurred) must report the event to the supporting agency head (or designee) and OHRP (45 CFR 46.103(b)(5)). Alternatively, the central monitoring entity may be designated to submit reports of unanticipated problems to the supporting agency head (or designee) and OHRP.

The HHS regulations at 46.103(b)(5) require written procedures for ensuring prompt reporting of unanticipated problems to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, any supporting department or agency head (or designee), and OHRP. The purpose of prompt reporting is to ensure that appropriate steps are taken in a timely manner to protect other subjects from avoidable harm.

The regulations do not define prompt. The appropriate time frame for satisfying the requirement for prompt reporting will vary depending on the specific nature of the unanticipated problem, the nature of the research associated with the problem, and the entity to which reports are to be submitted. For example, an unanticipated problem that resulted in a subject’s death or was potentially life-threatening generally should be reported to the IRB within a shorter time frame than other unanticipated problems that were not life-threatening. Therefore, OHRP recommends the following guidelines in order to satisfy the requirement for prompt reporting:

Unanticipated problems that are serious adverse events should be reported to the IRB within 1 week of the investigator becoming aware of the event.

Any other unanticipated problem should be reported to the IRB within 2 weeks of the investigator becoming aware of the problem.

All unanticipated problems should be reported to appropriate institutional officials (as required by an institution’s written reporting procedures), the supporting agency head (or designee), and OHRP within one month of the IRB’s receipt of the report of the problem from the investigator.

OHRP notes that, in some cases, the requirements for prompt reporting may be met by submitting a preliminary report to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, the supporting HHS agency head (or designee), and OHRP, with a follow-up report submitted at a later date when more information is available. Determining the appropriate time frame for reporting a particular unanticipated problem requires careful judgment by persons knowledgeable about human subject protections. The primary consideration in making these judgments is the need to take timely action to prevent avoidable harms to other subjects.

VI. What should the IRB consider at the time of initial review with respect to adverse events?

Before research is approved and the first subject enrolled, the investigator(s) and the IRB should give appropriate consideration to the spectrum of adverse events that might occur in subjects. In particular, in order to make the determinations required for approval of research under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.111(a)(1), (2), and (6), the IRB needs to receive and review sufficient information regarding the risk profile of the proposed research study, including the type, probability, and expected level of severity of the adverse events that may be caused by the procedures involved in the research. The investigator also should describe how the risks of the research will be minimized.

In addition, depending upon the risks of the research and the likelihood that the research could involve risks to subjects that are unforeseeable, the IRB must ensure, if appropriate, that the research includes adequate provisions for monitoring the data collected to ensure the safety of subjects (45 CFR 46.111(a)(6)). Such provisions typically would include monitoring, among other things, adverse events and unanticipated problems that may occur in subjects enrolled in the research. The HHS regulations at 45 CFR part 46 do not require that the IRB conduct such monitoring, and OHRP believes that, in general, the IRB is not the appropriate entity to monitor research.

OHRP notes that adequate monitoring provisions for research, if deemed appropriate by the IRB, might include one or more of the following elements, among others:

The type of data or events that are to be captured under the monitoring provisions.

The entity responsible for monitoring the data collected, including data related to unanticipated problems and adverse events, and their respective roles (e.g., the investigators, the research sponsor, a coordinating or statistical center, an independent medical monitor, a DSMB/DMC, and/or some other entity). (OHRP notes that the IRB has authority to observe or have a third party observe the research (45 CFR 46.109(e).)

The time frames for reporting adverse events and unanticipated problems to the monitoring entity.

The frequency of assessments of data or events captured by the monitoring provisions.

Definition of specific triggers or stopping rules that will dictate when some action is required.

As appropriate, procedures for communicating to the IRB(s), the study sponsor, the investigator(s), and other appropriate officials the outcome of the reviews by the monitoring entity.

The monitoring provisions should be tailored to the expected risks of the research; the type of subject population being studied; and the nature, size (in terms of projected subject enrollment and the number of institutions enrolling subjects), and complexity of the research protocol.

For example, for a multicenter clinical trial involving a high level of risk to subjects, frequent monitoring by a DSMB/DMC may be appropriate, whereas for research involving no more than minimal risk to subjects, it may be appropriate to not include any monitoring provisions.

For non-exempt research conducted or supported by HHS, the IRB must conduct continuing review of research at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk, but not less than once per year (45 CFR 46.109(e)). At the time of continuing review, the IRB should ensure that the criteria for IRB approval under HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.111 continue to be satisfied. In particular, the IRB needs to determine whether any new information has emerged – either from the research itself or from other sources – that could alter the IRB’s previous determinations, particularly with respect to risk to subjects. Information regarding any unanticipated problems that have occurred since the previous IRB review in most cases will be pertinent to the IRB’s determinations at the time of continuing review.

It may also be appropriate for the IRB at the time of continuing review to confirm that any provisions under the previously approved protocol for monitoring study data to ensure safety of subjects have been implemented and are working as intended (e.g., the IRB could require that the investigator provide a report from the monitoring entity described in the IRB-approved protocol).

OHRP recommends that, among other things, a summary of any unanticipated problems and available information regarding adverse events and any recent literature that may be relevant to the research be included in continuing review reports submitted to the IRB by investigators. OHRP notes that the amount of detail provided in such a summary will vary depending on the type of research being conducted. In many cases, such a summary could be a simple brief statement that there have been no unanticipated problems and that adverse events have occurred at the expected frequency and level of severity as documented in the research protocol, the informed consent document, and any investigator brochure.

OHRP recognizes that local investigators participating in multicenter clinical trials usually are unable to prepare a meaningful summary of adverse events for their IRBs because study-wide information regarding adverse events is not readily available to them. In such circumstances, when the clinical trial is subject to oversight by a monitoring entity (e.g., the research sponsor, a coordinating or statistical center, or a DSMB/DMC), OHRP recommends that at the time of continuing review local investigators submit to their IRBs a current report from the monitoring entity. OHRP further recommends that such reports include the following:

a statement indicating what information (e.g., study-wide adverse events, interim findings, and any recent literature that may be relevant to the research) was reviewed by the monitoring entity;

the date of the review; and

the monitoring entity’s assessment of the information reviewed.

For additional details about OHRP’s guidance on continuing review, see Guidance on Continuing Review - January 2007.

VIII. What should written IRB procedures include with respect to reporting unanticipated problems?

Written IRB procedures should provide a step-by-step description with key operational details for complying with the reporting requirements described in HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(b)(5). Important operational details for the required reporting procedures should include:

The type of information that is to be included in reports of unanticipated problems.

A description of which office(s) or individual(s) is responsible for promptly reporting unanticipated problems to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, any supporting department or agency heads (or designees), and OHRP.

A description of the required time frame for accomplishing the reporting requirements for unanticipated problems.

The range of the IRB’s possible actions in response to reports of unanticipated problems.

OHRP notes that many institutions have written IRB procedures for reporting adverse events, but do not address specifically the reporting requirements for unanticipated problems. Such institutions should expand their written IRB procedures to include reporting requirements for unanticipated problems.

Glossary for Key Terms

Adverse event: Any untoward or unfavorable medical occurrence in a human subject, including any abnormal sign (for example, abnormal physical exam or laboratory finding), symptom, or disease, temporally associated with the subject’s participation in the research, whether or not considered related to the subject’s participation in the research (modified from the definition of adverse events in the 1996 International Conference on Harmonization E-6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice).

External adverse event: From the perspective of one particular institution engaged in a multicenter clinical trial, external adverse events are those adverse events experienced by subjects enrolled by investigators at other institutions engaged in the clinical trial.

Internal adverse event: From the perspective of one particular institution engaged in a multicenter clinical trial, internal adverse events are those adverse events experienced by subjects enrolled by the investigator(s) at that institution. In the context of a single-center clinical trial, all adverse events would be considered internal adverse events.

Possibly related to the research: There is a reasonable possibility that the adverse event, incident, experience or outcome may have been caused by the procedures involved in the research (modified from the definition of associated with use of the drug in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a)).

Serious adverse event: Any adverse event temporally associated with the subject’s participation in research that meets any of the following criteria:

results in death;

is life-threatening (places the subject at immediate risk of death from the event as it occurred);

requires inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization;

results in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity;

results in a congenital anomaly/birth defect; or

any other adverse event that, based upon appropriate medical judgment, may jeopardize the subject’s health and may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the other outcomes listed in this definition (examples of such events include allergic bronchospasm requiring intensive treatment in the emergency room or at home, blood dyscrasias or convulsions that do not result in inpatient hospitalization, or the development of drug dependency or drug abuse).

(Modified from the definition of serious adverse drug experience in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a).)

Unanticipated problem involving risks to subjects or others: Any incident, experience, or outcome that meets all of the following criteria:

unexpected (in terms of nature, severity, or frequency) given (a) the research procedures that are described in the protocol-related documents, such as the IRB-approved research protocol and informed consent document; and (b) the characteristics of the subject population being studied;

related or possibly related to a subject’s participation in the research; and

suggests that the research places subjects or others at a greater risk of harm (including physical, psychological, economic, or social harm) related to the research than was previously known or recognized.

Unexpected adverse event: Any adverse event occurring in one or more subjects in a research protocol, the nature, severity, or frequency of which is not consistent with either:

the known or foreseeable risk of adverse events associated with the procedures involved in the research that are described in (a) the protocol–related documents, such as the IRB-approved research protocol, any applicable investigator brochure, and the current IRB-approved informed consent document, and (b) other relevant sources of information, such as product labeling and package inserts; or

the expected natural progression of any underlying disease, disorder, or condition of the subject(s) experiencing the adverse event and the subject’s predisposing risk factor profile for the adverse event.

(Modified from the definition of unexpected adverse drug experience in FDA regulations at 21 CFR 312.32(a).)

Examples of Unanticipated Problems that Do Not Involve Adverse Events and Need to be Reported Under the HHS Regulations at 45 CFR Part 46

An investigator conducting behavioral research collects individually identifiable sensitive information about illicit drug use and other illegal behaviors by surveying college students. The data are stored on a laptop computer without encryption, and the laptop computer is stolen from the investigator’s car on the way home from work. This is an unanticipated problem that must be reported because the incident was (a) unexpected (i.e., the investigators did not anticipate the theft); (b) related to participation in the research; and (c) placed the subjects at a greater risk of psychological and social harm from the breach in confidentiality of the study data than was previously known or recognized.

As a result of a processing error by a pharmacy technician, a subject enrolled in a multicenter clinical trial receives a dose of an experimental agent that is 10-times higher than the dose dictated by the IRB-approved protocol. While the dosing error increased the risk of toxic manifestations of the experimental agent, the subject experienced no detectable harm or adverse effect after an appropriate period of careful observation. Nevertheless, this constitutes an unanticipated problem for the institution where the dosing error occurred that must be reported to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, and OHRP because the incident was (a) unexpected; (b) related to participation in the research; and (c) placed subject at a greater risk of physical harm than was previously known or recognized.

Subjects with cancer are enrolled in a phase 2 clinical trial evaluating an investigational biologic product derived from human sera. After several subjects are enrolled and receive the investigational product, a study audit reveals that the investigational product administered to subjects was obtained from donors who were not appropriately screened and tested for several potential viral contaminants, including the human immunodeficiency virus and the hepatitis B virus. This constitutes an unanticipated problem that must be reported because the incident was (a) unexpected; (b) related to participation in the research; and (c) placed subjects and others at a greater risk of physical harm than was previously known or recognized.

The events described in the above examples were unexpected in nature, related to participation in the research, and resulted in new circumstances that increased the risk of harm to subjects. In all of these examples, the unanticipated problems warranted consideration of substantive changes in the research protocol or informed consent process/document or other corrective actions in order to protect the safety, welfare, or rights of subjects. In addition, the third example may have presented unanticipated risks to others (e.g., the sexual partners of the subjects) in addition to the subjects. In each of these examples, while these events may not have caused any detectable harm or adverse effect to subjects or others, they nevertheless represent unanticipated problems and should be promptly reported to the IRB, appropriate institutional officials, the supporting agency head and OHRP in accordance with HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.103(a) and 46.103(b)(5).

Examples of Adverse Events that Do Not Represent Unanticipated Problems and Do Not Need to be Reported under the HHS Regulationsat 45 CFR Part 46

A subject participating in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial comparing the relative safety and efficacy of a new chemotherapy agent combined with the current standard chemotherapy regimen, versus placebo combined with the current standard chemotherapy regimen, for the management of multiple myeloma develops neutropenia and sepsis. The subject subsequently develops multi-organ failure and dies. Prolonged bone marrow suppression resulting in neutropenia and risk of life-threatening infections is a known complication of the chemotherapy regimens being tested in this clinical trial and these risks are described in the IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document. The investigators conclude that the subject’s infection and death are directly related to the research interventions. A review of data on all subjects enrolled so far reveals that the incidence of severe neutropenia, infection, and death are within the expected frequency. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the occurrence of severe infections and death – in terms of nature, severity, and frequency – was expected.

A subject enrolled in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of a new investigational anti-inflammatory agent for management of osteoarthritis develops severe abdominal pain and nausea one month after randomization. Subsequent medical evaluation reveals gastric ulcers. The IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document for the study indicated that the there was a 10% chance of developing mild to moderate gastritis and a 2% chance of developing gastric ulcers for subjects assigned to the active investigational agent. The investigator concludes that the subject’s gastric ulcers resulted from the research intervention and withdraws the subject from the study. A review of data on all subjects enrolled so far reveals that the incidence of gastritis and gastric ulcer are within the expected frequency. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the occurrence of gastric ulcers – in terms of nature, severity, and frequency – was expected.

A subject is enrolled in a phase 3, randomized clinical trial evaluating the relative safety and efficacy of vascular stent placement versus carotid endarterectomy for the treatment of patients with severe carotid artery stenosis and recent transient ischemic attacks. The patient is assigned to the stent placement study group and undergoes stent placement in the right carotid artery. Immediately following the procedure, the patient suffers a severe ischemic stroke resulting in complete left-sided paralysis. The IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document for the study indicated that there was a 5-10% chance of stroke for both study groups. To date, 25 subjects have been enrolled in the clinical trial, and 2 have suffered a stroke shortly after undergoing the study intervention, including the current subject. The DSMB responsible for monitoring the study concludes that the subject’s stroke resulted from the research intervention. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the occurrence of stroke was expected and the frequency at which strokes were occurring in subjects enrolled so far was at the expected level.

An investigator is conducting a psychology study evaluating the factors that affect reaction times in response to auditory stimuli. In order to perform the reaction time measurements, subjects are placed in a small, windowless soundproof booth and asked to wear headphones. The IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document describe claustrophobic reactions as one of the risks of the research. The twentieth subject enrolled in the research experiences significant claustrophobia, resulting in the subject withdrawing from the research. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the occurrence of the claustrophobic reactions – in terms of nature, severity, and frequency – was expected.

A subject with advanced renal cell carcinoma is enrolled in a study evaluating the effects of hypnosis for the management of chronic pain in cancer patients. During the subject’s initial hypnosis session in the pain clinic, the subject suddenly develops acute chest pain and shortness of breath, followed by loss of consciousness. The subject suffers a cardiac arrest and dies. An autopsy reveals that the patient died from a massive pulmonary embolus, presumed related to the underlying renal cell carcinoma. The investigator concludes that the subject’s death is unrelated to participation in the research. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the subject’s pulmonary embolus and death were attributed to causes other than the research interventions.

An investigator performs prospective medical chart reviews to collect medical data on premature infants in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for a research registry. An infant, about whom the investigator is collecting medical data for the registry, dies as the result of an infection that commonly occurs in the NICU setting. This example is not an unanticipated problem because the death of the subject is not related to participation in the research, but is most likely related to the infant’s underlying medical condition.

NOTE: For purposes of illustration, the case examples provided above represent generally unambiguous examples of adverse events that are not unanticipated problems. OHRP recognizes that it may be difficult to determine whether a particular adverse event is unexpected and whether it is related or possibly related to participation in the research. In addition, the assessment of the relationship between the expected and actual frequency of a particular adverse event must take into account a number of factors including the uncertainty of the expected frequency estimates, the number and type of individuals enrolled in the study, and the number of subjects who have experienced the adverse event.

Examples of Adverse Events that Represent Unanticipated Problems and Need to be Reported Under the HHS Regulations at 45 CFR Part 46

A subject with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease enrolls in a randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial evaluating a new investigational agent that blocks acid release in the stomach. Two weeks after being randomized and started on the study intervention the subject develops acute kidney failure as evidenced by an increase in serum creatinine from 1.0 mg/dl pre-randomization to 5.0 mg/dl. The known risk profile of the investigational agent does not include renal toxicity, and the IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document for the study does not identify kidney damage as a risk of the research. Evaluation of the subject reveals no other obvious cause for acute renal failure. The investigator concludes that the episode of acute renal failure probably was due to the investigational agent. This is an example of an unanticipated problem that must be reported because the subject’s acute renal failure was (a) unexpected in nature, (b) related to participation in the research, and (c) serious.

A subject with seizures enrolls in a randomized, phase 3 clinical trial comparing a new investigational anti-seizure agent to a standard, FDA-approved anti-seizure medication. The subject is randomized to the group receiving the investigational agent. One month after enrollment, the subject is hospitalized with severe fatigue and on further evaluation is noted to have severe anemia (hematocrit decreased from 45% pre-randomization to 20%). Further hematologic evaluation suggests an immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. The known risk profile of the investigational agent does not include anemia, and the IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document for the study do not identify anemia as a risk of the research. The investigators determine that the hemolytic anemia is possibly due to the investigational agent. This is an example of an unanticipated problem that must be reported because the hematologic toxicity was (a) unexpected in nature; (b) possibly related to participation in the research; and (c) serious.

The fifth subject enrolled in a phase 2, open-label, uncontrolled clinical study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a new oral agent administered daily for treatment of severe psoriasis unresponsive to FDA-approved treatments, develops severe hepatic failure complicated by encephalopathy one month after starting the oral agent. The known risk profile of the new oral agent prior to this event included mild elevation of serum liver enzymes in 10% of subjects receiving the agent during previous clinical studies, but there was no other history of subjects developing clinically significant liver disease. The IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document for the study identifies mild liver injury as a risk of the research. The investigators identify no other etiology for the liver failure in this subject and attribute it to the study agent. This is an example of an unanticipated problem that must be reported because although the risk of mild liver injury was foreseen, severe liver injury resulting in hepatic failure was (a) unexpected in severity; (b) possibly related to participation in the research; and (c) serious.

Subjects with coronary artery disease presenting with unstable angina are enrolled in a multicenter clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of an investigational vascular stent. Based on prior studies in animals and humans, the investigators anticipate that up to 5% of subjects receiving the investigational stent will require emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery because of acute blockage of the stent that is unresponsive to non-surgical interventions. The risk of needing emergency CABG surgery is described in the IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document. After the first 20 subjects are enrolled in the study, a DSMB conducts an interim analysis, as required by the IRB-approved protocol, and notes that 10 subjects have needed to undergo emergency CABG surgery soon after placement of the investigational stent. The DSMB monitoring the clinical trial concludes that the rate at which subjects have needed to undergo CABG greatly exceeds the expected rate and communicates this information to the investigators. This is an example of an unanticipated problem that must be reported because (a) the frequency at which subjects have needed to undergo emergency CABG surgery was significantly higher than the expected frequency; (b) these events were related to participation in the research; and (c) these events were serious.

Subjects with essential hypertension are enrolled in a phase 2, non-randomized clinical trial testing a new investigational antihypertensive drug. At the time the clinical trial is initiated, there is no documented evidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) associated with the investigational drug, and the IRB-approved protocol and informed consent document do not describe GERD as a risk of the research. Three of the first ten subjects are noted by the investigator to have severe GERD symptoms that began within one week of starting the investigational drug and resolved a few days after the drug was discontinued. The investigator determines that the GERD symptoms were most likely caused by the investigational drug and warrant modification of the informed consent document to include a description of GERD as a risk of the research. This is an example of an adverse event that, although not serious, represents an unanticipated problem that must be reported because it was (a) unexpected in nature; (b) possibly related to participation in the research; and (c) suggested that the research placed subjects at a greater risk of physical harm than was previously known or recognized.

A behavioral researcher conducts a study in college students that involves completion of a detailed survey asking questions about early childhood experiences. The research was judged to involve no more than minimal risk and was approved by the IRB chairperson under an expedited review procedure. During the completion of the survey, one student subject has a transient psychological reaction manifested by intense sadness and depressed mood that resolved without intervention after a few hours. The protocol and informed consent document for the research did not describe any risk of such negative psychological reactions. Upon further evaluation, the investigator determines that the subject’s negative psychological reaction resulted from certain survey questions that triggered repressed memories of physical abuse as a child. The investigator had not expected that such reactions would be triggered by the survey questions. This is an example of an unanticipated problem that must be reported in the context of social and behavioral research because, although not serious, the adverse event was (a) unexpected; (b) related to participation in the research; and (c) suggested that the research places subjects at a greater risk of psychological harm than was previously known or recognized.

In all of these examples, the adverse events warranted consideration of substantive changes in the research protocol or informed consent process/document or other corrective actions in order to protect the safety, welfare, or rights of subjects.

NOTE: For purposes of illustration, the case examples provided above represent generally unambiguous examples of adverse events that are unanticipated problems. OHRP recognizes that it may be difficult to determine whether a particular adverse event is unexpected and whether it is related or possibly related to participation in the research.

Content created by Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)

Content last reviewed March 21, 2016

In our soon to be filed lawsuit we allege FDA is violating Costa Rica’s import laws which offer more human rights protections and forbid serious undue experimentation. All support is needed and appreciated to pay the Attorney fees!

End here with proof the experimenters do indeed talk in terms of tracking “EXPECTED outcomes”…

That’s fine, but what about the unexpected adverse events that actually have to be reported?

FROM 3 min VIDEO below called

“Regional Platform to Advance the Manufacturing of COVID 19 Vaccines in the Americas”:

Full video on top then screenshots are below:

Screenshots from above video with the words (confessions)

mRNA technology is in development…

“so we are tracking EXPECTED (anticipated) OUTCOMES”

The video is 2 years old and at the time they claim “we intend to have the first stages of scale up and production next year to conduct the NECESSARY CLINICAL TRIALS” - WTF isn’t that reverse order? Shouldn’t clinical trials come before scaling up production? Question: Did they ever do clinical trials or just mass human experimentation with lousy monitoring?

As you can see, the freshie experimenters beginning their journey in the ‘PAHO-WHO Regional Platform To Advance The Manufacturing of Covid Vaccines and Other Health Technologies in Latin America’ simply need to call some adverse effect “anticipated” or “expected”, even as crazy as DEATH, and track it, but by law they expressly do NOT need to report it to FDA or any regulator that we are aware of, because they knew it was expected for death to occur & they anticipated serious harms a mile long!!!…

These manufacturers just track the expected outcomes internally and obviously they help hide the adverse effects, because where are they to speak out? In silence, they march on, investing into the failing mRNA platform thats causing mass harm & death.

In our soon to be filed lawsuit we allege FDA is violating Costa Rica’s import laws which offer more human rights protections and forbid serious undue experimentation. All support is needed and appreciated to pay the Attorney fees!

Our Attorneys are asking us to pay them the monthly payments to work on refiling the Nuremberg Hearing as ordered by the Appellate court. We only need to raise $5000 this month to start the depositions for Crimes Against Humanity, which will go to ICC and the Costa Rica prosecutors who are working with us. We are asking readers for urgent help to pay and finish the expert depositions and finally file this important case with Dr. Yeadon, Dr. Janci Lindsay, Sasha Latypova and many other top experts. Nuremberg Code Anniversary today should remind everyone that we really need to work hard to protect what ethical norms our forefathers fought so hard to give us. Let’s litigate - don’t hesitate!

The evil powers are leaving no stone unturned. PURE EVIL.

Honestly, nothing surprises me anymore.