Costa Rica Judges Explain Scope & Application Of Universal Jurisdiction, Including, Information On The Relevant Applicable International Treaties & On Its National Legal Rules & Judicial Practice

How to sue for Crimes Against Humanity WITHOUT ICC! Contribution of the Third Chamber of the Supreme Court of Costa Rica, which hears appeals and requests for review on criminal matters in Costa Rica

Are The World's Most Powerful Criminal Judges In Costa Rica? Perhaps

Learn The Relevant Laws, Treaties And Rules Of The Game!

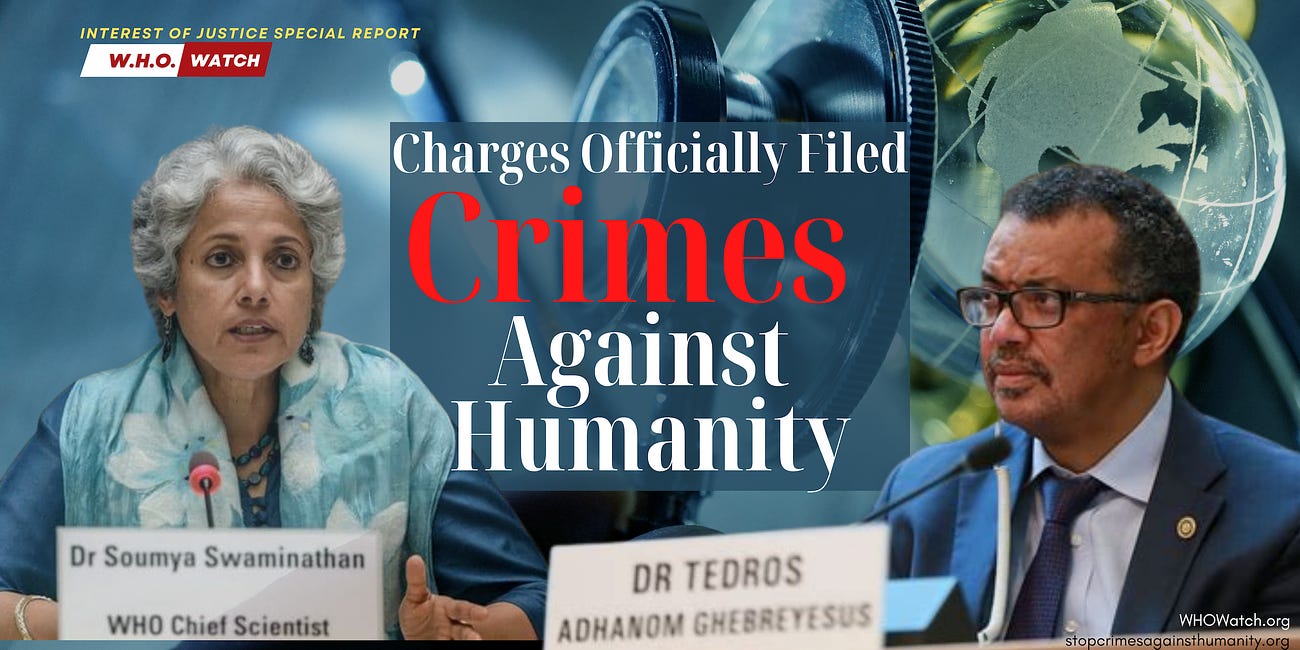

WHY & HOW We Have The Ability To Prosecute Covid Crimes Against Humanity.

Nuremberg 2.0 Is Coming To The Costa Rican Court of Universal Jurisdiction.

Below The Supreme Court Criminal Appeals Division Explains How To Prosecute Global Crimes Against Humanity.

Our criminal case for bioweapons and crimes against humanity is filed and starting to move through the slow but thorough system.

First, the updates most of you want to know: (to read the article by the Judges skip below)

See related reading about our criminal case for crimes against humanity & how we are now offered a hearing by the prosecutor:

This saga started in 2022 with our first complaints and filings, it’s now escalating to court!

IOJ commentary: What is Universal Jurisdiction?

Its Important! We are using it to achieve Justice For Humanity, so let’s all get up to speed. It Is Truly The Only Tool That Combats Impunity And The ‘Above The Law’ Antics Of Tyrants!

We can’t sue for Crimes Against Humanity without Universal Jurisdiction. Its key

We posted the following Article & Dr. Yeadon made a comment on his Telegram, which is posted below

This is interesting. I’ve no knowledge of law, especially relating to acts which, under international law, are crimes against humanity.

As a legal amateur, it’s seems to me probable that what my government (U.K.) has done & keeps doing, coercing people to accept an intentionally toxic injection, while lying about the need for it, is a crime against humanity.

There are probably several such crimes.

Of course, one of the major barriers to it’s recognition is finding a suitably constituted court & judge capable to try such alleged crimes & hand down judgements.

For this to happen would require a very courageous person. Not very likely. But we will try, no least because it may act as a method & approach pathfinder.

Best wishes

Mike

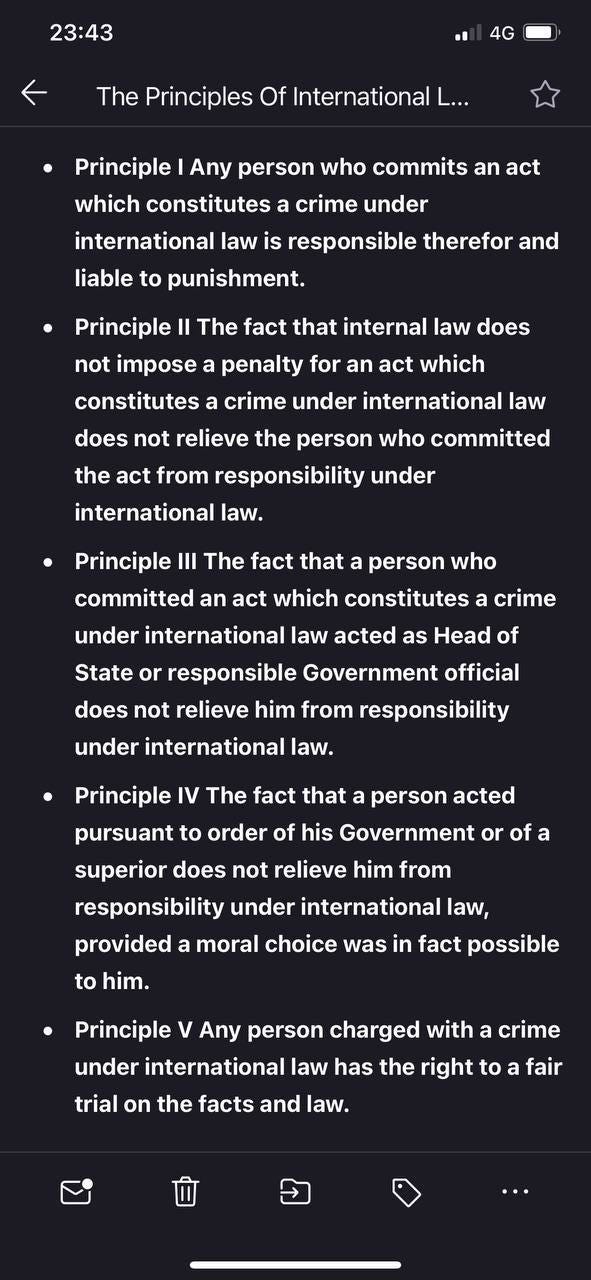

UN document below is describing precisely how they can be criminally prosecuted in Costa Rica if guilty.

Below Costa Rica Judges Explain Scope & Application Of Universal Jurisdiction In Costa Rica, Including, Information On The Relevant Applicable International Treaties & On Its National Legal Rules & Judicial Practice

Read UN Report Below, It's Actually Very Informative & Gives Hope... It contains ALL laws we need to beat them.

Find doc here: https://www.un.org/en/ga/sixth/76/universal_jurisdiction/costarica_e.pdf

2104008E 1 Translated from Spanish

Read the most bad ass article, by bad ass judges below:

General Directorate for Foreign Policy Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship

Information from Costa Rica on the scope and application of universal jurisdiction, including, where appropriate, information on the relevant applicable international treaties and on its national legal rules and judicial practice.

Contribution of the Third Chamber of the Supreme Court of Costa Rica, which hears appeals and requests for review on criminal matters

There is no single definition of the concept of universal jurisdiction (or the principle of universality or of global justice). The concept has traditionally been understood as an exception in international law, since by rule, States exercise national jurisdiction as part of their sovereignty, and therefore have the power or authority to prosecute (institute criminal proceedings against) persons under investigation for certain acts established by law as illicit.

A further difference must be pointed out. Universal jurisdiction does not require double criminality. The exercise of universal jurisdiction does not require that the act is punishable at the place of its commission and does not depend on whether the accused was found to be on national territory and was not extradited. Universal jurisdiction is thus an important tool in the fight against impunity.

At the legislative level, Costa Rica has made significant progress on the concept of universal jurisdiction, given that, approximately 20 years ago, it specifically prohibited prosecution for offences committed outside the country in article 7 of the 1973 Penal Code, which stipulated that “no national or foreigner may be prosecuted in Costa Rica, in accordance with the provisions of the preceding articles, for offences or quasi-offences committed outside the country...”.

In 2001, Costa Rica introduced a significant amendment that allowed for the application of universal jurisdiction through Act No. 8272 on criminal sanctions as punishment for war crimes and crimes against humanity, which amended the aforementioned article 7 to read as follows: “Irrespective of the provisions in force in the place where the offence was committed and the nationality of the perpetrator, any person who commits acts of piracy or acts of genocide; forges coins, securities, banknotes and other bearer instruments; participates in the trafficking of slaves, women or children; or engages in trafficking of narcotics or obscene publications, shall be prosecuted under Costa Rican law. Any person who commits any other offence against human rights and international humanitarian law, as established in the treaties signed by Costa Rica or in this Code, shall also be prosecuted.”

Article 7 was later amended in 2009, through Act No. 8719 on the strengthening of counter-terrorism laws, with the addition of the offences of terrorism, the financing of terrorism and such related offences as trafficking in weapons or explosive materials.

In 2011, it once again amended article 7, which now read:

“Irrespective of the provisions in force in the place where the offence was committed and the nationality of the perpetrator, any person who commits acts of piracy, acts of terrorism or its financing, or acts of genocide; forges coins, securities, banknotes and other bearer instruments; smuggles weapons, ammunition, explosives or related materials; participates in the trafficking of slaves, women or children; commits sexual offences against minors; or engages in trafficking of narcotics or obscene publications, shall be prosecuted under Costa Rican law. Any person who commits any other offence against human rights and international humanitarian law, as established in the treaties signed by Costa Rica or in this Code, shall also be prosecuted.”

In 2019, the Costa Rican legislator broadened the scope of universal jurisdiction by no longer restricting its application to such serious offences as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, offences against the security of the State, forgery of the State seal or national currency, acts of terrorism, attacks, plots and other crimes against the authority of the State or the integrity of the national territory, offences that might disrupt public order, and acts of torture, as set out in most laws around the world. Instead, the legislator introduced an amendment, through the Act on the responsibility of legal persons for domestic bribery, transnational bribery and other offences (Act No. 9699 of 10 June 2019), to include other illegal acts not covered in existing laws. It stipulated that, “irrespective of the provisions in force in the place where the offence was committed and the nationality of the perpetrator, any person who commits acts of piracy, acts of terrorism or funds terrorist activities, or acts of genocide; forges coins, securities, banknotes and other bearer instruments; smuggles weapons, ammunition, explosives or related materials; participates in the trafficking of slaves, women or children; commits sexual offences against minors; or engages in trafficking of narcotics or obscene publications, shall be prosecuted under Costa Rican law. Any person who commits the offences of illicit enrichment; criminal receipt, legalization or concealment of goods; legislation or administration for personal gain; irregular overpricing; misrepresentation of the receipt of goods and services contracted; irregular payment of administrative contracts; influence peddling; transnational bribery and influence against the Ministry of Finance, offences covered by Act No. 8422 of 6 October 2004 against corruption and illicit enrichment in the public service, as well as the offences of bribery in which the person being bribed commits acts not prohibited by law; bribery in which the person being bribed commits acts constituting a criminal offence; aggravated corruption; acceptance of gifts for an accomplished act; corruption of judges; active bribery; inappropriate business dealings; embezzlement; misappropriation; and embezzlement and misappropriation of private funds under this Code. Any person who commits any other offence against human rights and international humanitarian law, as established in the treaties signed by Costa Rica, in this Code or in other special laws, shall also be prosecuted”.

This new version, which is currently in force, is novel in that it classifies most offences against the Treasury, as well as administrative and transnational bribery, as acts or conduct for which persons can be prosecuted on the basis of universal jurisdiction.

IOJ Interruption based on the above bolded and conspicuous paragraph:

Question: Did Pfizer lie to make a ton of cash? Like Pirate booty? Watch the excellent compilation below & ask: Is it proof of a crime?

MUST WATCH VIDEO OF PFIZER CEO

Information on the relevant applicable international treaties and on their legal rules

Article 7 of the Constitution of Costa Rica stipulates that “public treaties, international agreements and concordats duly adopted by the Legislative Assembly shall have a higher authority than laws, upon their adoption or from the date stipulated. Public treaties and international agreements concerning the territorial integrity or political organization of the country shall require the approval of the Legislative Assembly, by a vote of no less than threequarters of its membership, and that of two thirds of the members of a constituent assembly convened for that purpose. (As amended by the sole article of Act No. 4123 of 31 May 1968)...”

Article 48 of the Constitution provides that “everyone shall have the right to bring habeas corpus proceedings to protect his personal freedom and integrity, and to bring amparo proceedings to maintain or re-establish his enjoyment of the other rights embodied in this Constitution and of the fundamental rights recognized in the international human rights instruments in force in the Republic. Both these remedies shall be within the jurisdiction of the Chamber mentioned in article 10. (As amended by article 1 of Act No. 7128 of 18 August 1989)...”.

The Supreme Court has used these two constitutional provisions as cover to interpret the scope of articles 7 and 48 broadly, ruling that, when it comes to human rights, the application of international human rights conventions and treaties in the country is not limited to those that have been ratified, but may also extend to those that have not been unratified. Thus, despite the fact that there is abundant case law on the subject, it is worth highlighting judgment No. 2019- 012242, issued at 9:45 a.m. on 5 July 2019, which stipulated that “in accordance with article 48 of the Basic Law, the protection afforded by human rights instruments is not limited to conventions and treaties formally ratified by Costa Rica, or to conventions, treaties or agreements formally signed and approved in accordance with constitutional procedure. Rather, that protection extends to any other instrument that provides for the protection of human rights, even if it has not been formally signed or approved in accordance with constitutional procedure (on this topic, refer to judgments Nos. 2007-001682 issued at 10.34 p.m. on 9 February 2007, 2007-03043 issued at 2.54 p.m. on 7 March 2007 and 2007-004276 issued at 2.49 p.m. on 27 March 2007)”.

The special protection of human rights explicitly enshrined in our Political Constitution is relevant to the topic of universal jurisdiction insofar as the latter applies to grave offences against international law; consequently, even if the Legislative Assembly has not ratified the treaty or convention in question, it may be applied in national courts if the offence in question concerns human rights.

The following treaties related to the subject have been duly ratified by Costa Rica:

Relevant treaties and conventions

− American Convention on Human Rights, or Pact of San José. Act No. 4534 of 23 February 1970, published on 14 March 1970

− International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its Optional Protocol. Act No. 4229 of 11 December 1968, published on 17 December 1968

− International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Act No. 4229 of 11 December 1968, published on 17 December 1968

− First Geneva Convention (art. 49), ratified on 15 October 1969 − Second Geneva Convention (art. 50), ratified on 15 October 1969

− Third Geneva Convention (art. 129), ratified on 15 October 1969 − Fourth Geneva Convention (art. 146), ratified on 15 October 1969

− Rome Statute, ratified on 7 June 2001 − Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: approved by Act No. 7351 of 21 July 1993

− Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: ratified by Act No. 33134, published in Official Gazette No. 228 of 25 November 2005

− United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (2000 Palermo Convention). Act No. 8302 of 12 September 2002, published in Official Gazette No. 123 of 27 June 2003

− Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Act No. 8315 of 26 September 2002, published in Official Gazette No. 212 of 4 November 2002

− International Slavery Convention and Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery − Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Act No. 3844 of 16 December 1966, published in the Official Gazette of 7 January 1967

− Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Act No. 8089 of 6 March 2001, published in the Official Gazette of 1 August 2001

− Convention on the Rights of the Child and Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. Act No. 8172 of 7 December 2001, published on 11 February 2002

− Protocol to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Act No. 6079 of 29 August 1977, published on 5 October 1977 − Statute of the International Criminal Court. Act No. 8083 of 7 February 2001, published on 20 March 2001

− Charter of the Organization of American States − Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, Convention of Belém do Pará. Act No. 7499 of 2 May 1994, published on 28 June 1995

− Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities. Act No. 7948 of 22 November 1999, published on 8 December 1999 − Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Act No. 8661 of 19 August 2008, published on 29 September 2008

− Inter-American Convention on International Traffic in Minors Act No. 8071 of 14 February 2001, published on 21 May 2001 − Inter-American Convention on the International Return of Children. Act No. 8032 of 19 October 2000, published on 10 November 2000

− Convention on the Law of the Sea (art. 105), ratified on 21 September 1992

− 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (art. 28), ratified on 13 June 1998

− 1999 Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (art. 16), acceded on 9 December 2003

− 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (art. 7), ratified on 11 November 1993 2104008E 7

− 1970 International Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft (art. 4.2), ratified on 9 July 1971

− 1973 Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (art. 5), acceded to on 15 October 1986

− International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism (arts. 9-11), ratified on 21 February 2013

− 1979 International Convention against the Taking of Hostages (art. 5.2), acceded to on 24 January 2003

− 1997 International Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings

− 1973 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes against Internationally Protected Persons (art. 7), acceded to on 2 November 1977

− United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (art. 4.2.b), ratified on 8 February 1991

− United Nations Convention against Corruption, (art. 42.4), ratified on 21 March 2007

− Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, arts. 12 and 14), ratified on 8 February 2000

− 1994 Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons (arts. 4 and 5), ratified on 2 June 1996

Reservations and declarations in respect of international treaties

In respect of criminal matters and the aforementioned international treaties, Costa Rica has not made any reservations or declarations that are worth noting as relevant to universal jurisdiction.

Political Constitution and laws 1949 Constitution of Costa Rica

Penal Code of 15 November 1970. Act No. 4573

Act No. 8083 of 7 February 2001, pursuant to which the Rome Statute was approved

Act No. 8272 of 2 May 2002. Criminal sanctions as punishment for war crimes and crimes against humanity

Trafficking in Persons Act and establishment of the National Coalition against Smuggling of Migrants and Trafficking in Persons, or Act No. 9095 of 26 October 2012 Agreement with the United States of America to suppress illicit traffic in narcotic drugs

Good domestic judicial practices in the application of universal jurisdiction

In terms of training on the application of universal jurisdiction, Costa Rica has established a professional arrangement whereby the judiciary, in coordination with officials of the International Court of Justice in the Hague, will update the relevant technical knowledge required of officials who may be called upon to address matters related to universal jurisdiction.

To that end, the judiciary’s knowledge management unit, known as the Judicial Training College, is designing a course on the International Criminal Court. The course will feature written and digital teaching aids, the latter in the form of Spanish-language materials donated by the Court to the country.

As a result of the agreement concluded with the United States of America to suppress illicit traffic in narcotic drugs, Costa Rica has been able to effectively process and prosecute universal jurisdiction cases involving organized crime and direct links to drug trafficking. In response to the significant and ongoing increase in drug trafficking, the agreement has made it possible to carry out numerous seizures on the high seas and outside our borders with the assistance of United States frigates on patrol, which alert the coasts as soon as they spot speedboats, fishing vessels (under the flags of different countries), semi-submersibles and taxi boats beyond the territorial sea. The frigates bring the vessels and crew members into Costa Rican ports, where the local authorities await them to make seizures and arrests and later prosecute cases.

To systematically incorporate a gender perspective by including gender-sensitive analyses in their contributions, the importance of reflecting a gender perspective in their contributions

According to the website, https://secretariagenero.poderjudicial.go.cr/index.php/comisiondegenero, which can be accessed via the site of the judiciary of Costa Rica, the Commission on Gender was established in 2000 as a result of the first Congress of Women Judges of Latin America and the Caribbean, held under the theme “For gender justice”. The Declaration of the first Congress of Women Judges of the Supreme Courts and Constitutional Courts of Latin America and the Caribbean was adopted as an outcome of the Congress. The aim of the Declaration is “to promote the institutional mainstreaming of gender and its integration into the administration of justice, as well as to request that a gender perspective be incorporated into programmes aimed at modernizing and reforming the judiciary, as an integral part of the implementation of this Declaration”. In response to the recommendations made at that congress, the full Court (all the justices that comprise the Costa Rican judiciary) formed the Commission on Gender at session 12-2001, held on 2 April 2001, article VII. Later, in 2002, the Technical Secretariat for Gender Issues and Access to Justice was established. According to the 2020 report on its activities, the Technical Secretariat aims to “identify obstacles faced by women in gaining access to justice and in the formulation of measures to...overcome those obstacles. It is clear that such measures remain inadequate and that a planned effort sustained over time will be required, along with assessments of the progress achieved in order to gauge the impact of those measures”. The Commission on Gender formulates public policy guidelines for the implementation of the judiciary’s gender equality policy, and the Technical Secretariat for Gender Issues and Access to Justice implements those guidelines.

The following is a description of the main activities carried out by the Technical Secretariat in 2020. These activities may be closely related to the topic of universal jurisdiction once the mainstreaming of a gender perspective is transposed from the national arena to the international arena.

• Adoption of the gender equality policy of the judiciary, approved in 2005, whose aim is to mainstream a gender perspective within the internal structure of the judiciary, and in the services it provides to facilitate access to justice 2104008E 10

• Establishment of the Commission against Domestic Violence is coordinated by Judge Chacón, with technical support from the Technical Secretariat

• Support for the work of the Integrated Victim Services Platform, which is coordinated by Judge Chacón, as coordinator of the Commission on Gender

• Mainstreaming of a gender perspective in institutional training, in coordination with the Judicial Training College and the training units

• Promotion of the use and monitoring of Gesell chambers to prevent revictimization.

• Organization of information and awareness-raising campaigns on various topics related to its areas of work: inclusive language, sexual harassment, sexual harassment in public spaces, positive masculinities

• Participation in the National Gender Unit Network in the public sector in order to integrate a gender perspective into measures taken at the institutional level

• Coordination and monitoring of the rapid response teams programme for the comprehensive care of victims of rape and sexual offences, an inter-agency programme with interdisciplinary teams made up of representatives from the judiciary, the Costa Rican Social Insurance Fund and the Technical Secretariat for Gender Issues and Access to Justice

• Legal affairs: since 2016, judicial employees who have been victims of sexual harassment, intimate partner violence and discrimination on the basis of ethnic or national origin, skin colour, culture, sex gender, age, disability, sexual preference or gender identity have received legal representation, advice and support. The Technical Secretariat for Gender Issues and Access to Justice also responds to queries and provides people with guidance on issues related to its work

• Formulation of the institutional policy on the use of inclusive language and monitoring the implementation thereof

• Coordination and implementation of agreements concluded by the judiciary’s Men’s Collective in favour of Gender Equality

• Coordination and implementation of agreements concluded by the Subcommittee against Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.

• Coordination and implementation of agreements concluded by the judiciary Subcommittee against Sexual Harassment 2104008E 11

• The Observatory on Gender-based Violence against Women and Access to Justice is part of the Technical Secretariat. Its purpose is to systematize, inform, analyse and evaluate the actions taken by the Costa Rican judiciary to address, investigate and punish the various forms of violence against women and guarantee their access to justice.

Jurisprudence:

In its judgment No. 2000-09685, issued at 2.56 p.m. on 1 November 2000, the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court referred to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, ratified by Costa Rica, as an international legal instrument pursuant to which the International Criminal Court was established. The Court is a body that is complementary to, not a replacement for, national criminal courts. It is a permanent institution that shall have the power to exercise its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole, namely the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. As can be inferred from the Rome Statute, the Court will be the last resort for punishing the perpetrators of (even though not in the Spanish) crimes that meet the gravity threshold and, as indicated, it is rooted in the principle of complementarity inasmuch as it is not meant to replace national courts but rather to complement them. In that sense, it will act only when the competent national courts are unable or unwilling to fulfil their obligation to investigate or prosecute the alleged perpetrators of the offences established in the Statute, with a view to putting an end to impunity for crimes.

In ruling on whether the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court is constitutional and therefore in line with the Costa Rican Constitution (judgment No. 00-9685), the Chamber recognized the seriousness of the grave human rights violations committed in recent years (e.g. the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda), and throughout the twentieth century in general, during which millions of children, women and men became the victims of atrocious crimes that went unpunished. The Rome Statute was thus conceived in response to that state of affairs, in order to ensure that the perpetrators of the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression in their various forms are brought to justice. At the time, the importance of the imprescriptibility of war crimes and crimes against humanity was highlighted, something which the Chamber also referred to in its judgment No. 230-96, in which it recognized the legitimacy of the imprescriptibility of the criminal activities stipulated in the Inter-American Convention on the Forced Disappearance of Persons (signed by our country in Belém, Brazil, on 9 June 1994). In that judgment, the Chamber made a distinction between ordinary crimes and crimes against humanity, in terms of the degree of perversion and harm to specially protected legal interests, which justifies different treatment from the legislator.

Article 89 of the Rome Statute empowers the Court to request from States Parties the arrest and surrender of an accused person for trial before it. Since article 89 makes no reference to the nationality of the person whose arrest and surrender is requested by the Court, it must by definition mean that the request may concern either a national of the State in whose territory the person may be found, or a foreigner. From the Costa Rican legal standpoint, the detention and surrender of a foreigner does not create any conflicts with the Constitution, because there is no provision in the Constitution that could be invoked to prevent the foreigner’s arrest and surrender under the Statute. However, the issue becomes problematic if the person is a Costa Rican national. This is because article 32 of the Constitution stipulates that “no Costa Rican may be compelled to leave the national territory”. The verb “to compel”, as we know, means to coerce a person, by using force or authority, to do something that the person does not wish to do. Since the constitutional provision makes no explicit distinctions regarding, for instance, motives or purposes, a plain reading of the provision and its wording suggests that Costa Ricans cannot be compelled to leave the national territory for any reason, regardless of the intended purpose, meaning that such compulsion will always be illegitimate; in other words, article 32 as worded, if understood in this manner, means that Costa Ricans enjoy absolute territorial protection, applicable in any and all conceivable cases, both from openly arbitrary, illegitimate or spurious actions taken by the State and from any other type of acts or actions, even if the acts or actions do not appear arbitrary, illegitimate or spurious. Examples include such hypothetical situations as those that arise when article 89 of the Rome Statute is implemented. The question that arises is whether article 32 of the Constitution contains an absolute guarantee for Costa Ricans, as the literal interpretation described above would suggest, or instead, whether that guarantee is not absolute, so that article 32, properly understood, would mean that the guarantee cannot have the effect of impeding other instruments for the protection and enforcement of human rights, specifically that established under the Rome Statute.

Costa Rica's Universal Jurisdiction Is a Constitutional Guarantee & Allows Real Trials For Crimes Against Humanity.

Support:

We have an opportunity for a criminal hearing with experts such as Dr. Yeadon, Dr. Ana Mihalcea, Dr. Janci Lindsay, Sasha Latypova and other top experts. Help us make this happen, kick ass in court and build a very solid case for the attack on humanity.

The experts and IOJ need your help to fund the April bills : ) We finally got the down payment paid off thanks to awesome supporters and are excited to ensure the mission carries forward until complete!

StopCrimesAgainstHumanity.org/donate

![How Is Nuremberg Code Enforceable? Court Hearing ORDERED For November 9, 2023 To Take Covid-19 [non] Vaccines OFF The Market](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa18194fd-abc3-4e8c-9cd6-c532d2830eb2_474x316.jpeg)

Holy COW! This is a very bad time to not have pots of 'extra' money... and 'carbon taxes' going up 23%, for faster citizen bankruptcy...

In Australia they just signed a bill introducing Digital ID for everyone. Communism on steroids. Next will be CBDCs. They can't do this stuff fast enough because they know we are coming after them. They're so stupid, because when we have nothing left to lose, we'll have nothing left to lose, if you know what I mean 😉