The Most Important Authority On The Matter Of Genocide and International Law: Professor Chabas Gives Best Lecture Ever On New Hopeful Legal Developments

Current Legal Position On Genocide Convention & Crimes Against Humanity - Going through the four open cases and examining an extremely volatile and dynamic period in public international law

Hope For Humanity? We need hope!

This Is The Great Reset Of Rule of Law

Things simply cannot stay the same.

… “we now have four genocide cases pending before the International Court of Justice.

This is an unprecedented situation.

They are joined by other cases dealing with human rights, both contentious cases and two advisory opinions that are also pending before the International Court of Justice dealing with other human rights issues.”

… So taken as a whole, we have close to 50 states that have intervened directly in these proceedings. And that's not counting all of the states who are supporting the proceedings from the organization of the Islamic conference.

And I don't think this has ever before happened in international law.

And I think as a general proposition, It shows a new willingness of states to litigate human rights issues at the multilateral level in a judicial environment, and driven, I think, probably by a degree of frustration with where these issues have been settled in the past, which is in the political organs of bodies like the United Nations, the Human Rights Council, the General Assembly, and the Security Council, where, of course, double standards are the rule, where we have states that will say one thing one day and another the other day because it suits their political agendas.

This morning we posted about the presumed governmental depopulation based murder of our co-founder Lady Xylie’s parents. All we can say is the topic of crimes against humanity and genocide are close to our hearts and we are working on it.

This lecture below is really bad ass and teaches even the wisest scholars more than you may ever want to know on the history of Nuremberg Code, Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity laws as they currently stand and a they are currently evolving.

Long Post, But Bad Ass & Worth Reading In Full - or listen on Youtube:

We also added a few “shorts” for you to watch some key excerpts.

All in all, the takeaway should be that there is hope that the international community is moving toward a strengthened international order and legal system to be able to finally deal with these heinous crimes.

NOTICE: There Are Currently Four Genocide Cases Pending, With An Unprecedented 50 Interventions

International Law Moves From Political Force To JUDICIAL FORCE - Tides Of Change Coming?

Such a fascinating an informative lecture, this is well worth a read or listen for any history or legal researcher. MUST SHARE for any one interested in this obscure topic.

It’s so good we even had to take notes. - IOJ

Genocide - The Crime of Crimes

In this enlightening lecture, Professor William Chabas discusses the evolving landscape of genocide law, the historical context of the Genocide Convention, and the current cases pending before the International Court of Justice.

He shares his personal journey into the field of genocide law, emphasizing the importance of intent in legal definitions and the challenges faced in prosecuting genocide. The conversation also highlights the role of states in addressing human rights issues through litigation and the significance of Brazil's potential intervention in ongoing cases.

takeaways

The role of states in litigating human rights issues is increasing.

The crime of genocide is evolving in international law.

The International Court of Justice is becoming a key player in human rights litigation.

Intent to destroy is a critical element in proving genocide & the challenges of proving genocidal intent complicate prosecutions.

Brazil's potential intervention in international cases could be significant.

The current geopolitical climate influences the prosecution of genocide.

This Is A Critical Lecture - Packed With Little Known Info On Genocide Laws

Video transcribed below:

Chapters

00:00 Introduction to Genocide and International Law

03:20 Current Landscape of Genocide Cases

12:02 Personal Journey into Genocide Law

17:57 Historical Context of Genocide Law

25:44 The Genocide Convention: Scope and Challenges

35:33 Analysis of Current Genocide Cases

51:25 Concluding Thoughts and Future Directions

INTRODUCTION TO PROF CHABAS

(Can skip - but has his credentials which are pretty bad ass - a hero to IOJ)

Muito bom dia a todos. Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. It is a pleasure and an honor for us today to have Professor William Chabas lecturing on genocide, the crime of crimes. When we invited Professor Chabas, and he was kind enough to accept our invitation, Professor Chabas mentioned that it was the first time he had the opportunity of working with USP, with the University of Sao Paulo. We are very glad that you accepted our invitation and this may be the first of other initiatives we can work together on.

And this initiative, the Permanent Forum on Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity of the University of Sao Paulo, is an initiative of three units of the university. The Professor Alain Plaménche from Arab History in the Philosophy and Human Sciences Faculty, Professor Arthur Capella from the Institute of International Relations of WUSP, myself from the Public International Law in the of University of São Paulo Law School and Professor Filipe Alamino from FADISP. This is an important end. We were also joined by the Institute of Advanced Studies of the University of São Paulo. So we have an initiative that is joining three and plus one, four units of the university.

Professor Chabas is Professor of International Law at Middlesex University, London, Emeritus Professor at Leiden University and the University of Galway, and distinguished visiting faculty at the University of Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po. A third edition of his book, Genocide in International Law, is to be published in late 2024. Other recent publications include the International Legal Orders, COLO Line, and the Customary International Law of Human Rights.

Professor Chabas is an officer of the Order of Canada and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. In 2014, he served as chairman of the UN Commission of Inquiry into the Gaza conflict.

LESSON BY PROF CHABAS BELOW:

We have the opportunity of listening today to the most important authority on the matter of genocide and international law. Professor Chabas, with our thanks and our honored compliments, you have the floor, please.

Well, thank you very much. Thank you for inviting me to deliver this talk. It's a subject that continues to evolve, one of great interest and one that I'm continuing to follow. I learned from my publisher that actually the third edition of my book will be delayed, perhaps a few months. So I'm expecting to see it early in February, but it couldn't come at a more timely moment.

It's a revision of a text that was last revised more than 15 years ago and the landscape of the crime of genocide has developed immensely in that period.

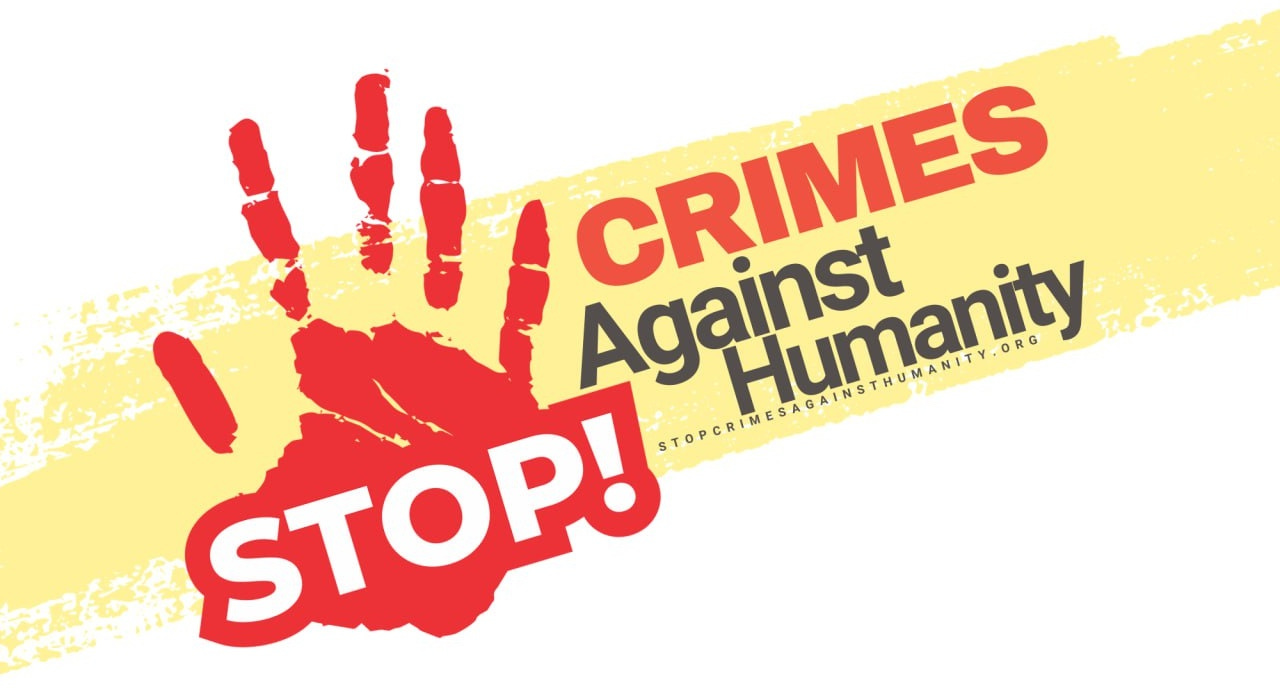

I've taken the quote, times of perplexity and tumult from the opinion of Judge Al -Khwasani in the recent decision in the genocide case filed by Nicaragua against Germany.

It seemed a very eloquent way of talking about what is an extremely volatile and dynamic period in public international law generally, but also in terms of the law of genocide, where we now have four genocide cases pending before the International Court of Justice. This is an unprecedented situation. They are joined by other cases dealing with human rights, both contentious cases and two advisory opinions that are also pending before the International Court of Justice dealing with other human rights issues.

UN & the evolution of Human Rights Courts

I say that many, many years ago when the United Nations was first beginning, there was talk of setting up a human rights court within the United Nations. And this has never happened despite various attempts to revive the idea and the strange situation where we have very successful human rights courts at the regional level, the Inter -American Court of Human Rights, the European Court of Human Rights, the African Court of Human People's Rights.

But I have the impression that in the last few years, the International Court of Justice has now taken over that mantle as the global court of human rights with all of this litigation. And as I say, at the core, at the heart of it, are these four cases.

So let me very briefly just describe what's so extraordinary about them.

The first case was filed not quite four years ago by the Gambia versus Myanmar. This is a case in which the Gambia is not an injured state in any respect, but where the Gambia has simply taken on its perceived duty as a member of the world community to litigate the issue of genocide with another state. And in that initiative, it has been supported. It was in effect mandated to do this by the organization of the Islamic Conference, which has 57 member states.

Gambia’s heroic move - Duty to Protect!

Other countries followed their lead! Someone has to take the first steps! - IOJ

But very recently, within the last 10 months, there have been interventions in the proceedings. So six Western states, Canada, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark filed a joint intervention in the case under Article 63 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

And shortly afterwards, the Maldives also filed an intervention.

These seven states set out their interpretation of the Genocide Convention and were at least indirectly intervening to support the case of the Gambia.

The second case, Ukraine versus Russia, filed very shortly after the Russian invasion at the end of February of 2022. And there have been in that case, 33 interventions essentially by Western states in the proceedings.

Then maybe the most famous of them all, the case filed by South Africa against Israel at the end of December of 2023. And there we have interventions by Nicaragua, Colombia, Libya, Mexico, Egypt, Ireland, Spain, Palestine, Libya, Chile, and more are promised.

And it's interesting to see the global reach, including several states in the Western hemisphere who have either intervened or have pledged to do so.

And then finally, the case filed by Nicaragua against Germany. But this case concerns Germany's failure to prevent genocide in Gaza and Germany's support and complicity alleged by Nicaragua in the conflict in Gaza.

So taken as a whole, we have close to 50 states that have intervened directly in these proceedings. And that's not counting all of the states who are supporting the proceedings from the organization of the Islamic conference. And I don't think this has ever before happened in international law.

And I think as a general proposition, It shows a new willingness of states to litigate human rights issues at the multilateral level in a judicial environment, and driven, I think, probably by a degree of frustration with where these issues have been settled in the past, which is in the political organs of bodies like the United Nations, the Human Rights Council, the General Assembly, and the Security Council, where, of course, double standards are the rule, where we have states that will say one thing one day and another the other day because it suits their political agendas.

It's harder to do this in a judicial environment. It's not as if the judicial environment is immune to double standards, but it's harder to say different things one day and the next when you put them down in writing.

And just to give you an example of this, in the case of Gambia versus Myanmar, the six Western countries filed an intervention arguing for a broad approach to the definition of genocide.

They said that it's too hard to prove genocide, they cited Judge Kansaldo Trindade, who in the 2015 case of Croatia versus Serbia, argued for a more relaxed approach to proving genocidal intent.

And they said that genocidal intent would be manifested in things like victimization of children in the conflict and forced displacement within the borders of a country during a conflict.

And they could not have anticipated when they filed this joint intervention that barely weeks later, South Africa would file an application against Israel where the very arguments that those states were making in favor of the Gambia against Myanmar would provide support and assistance to South Africa in its case against Israel, which cannot have been their desire or their intention.

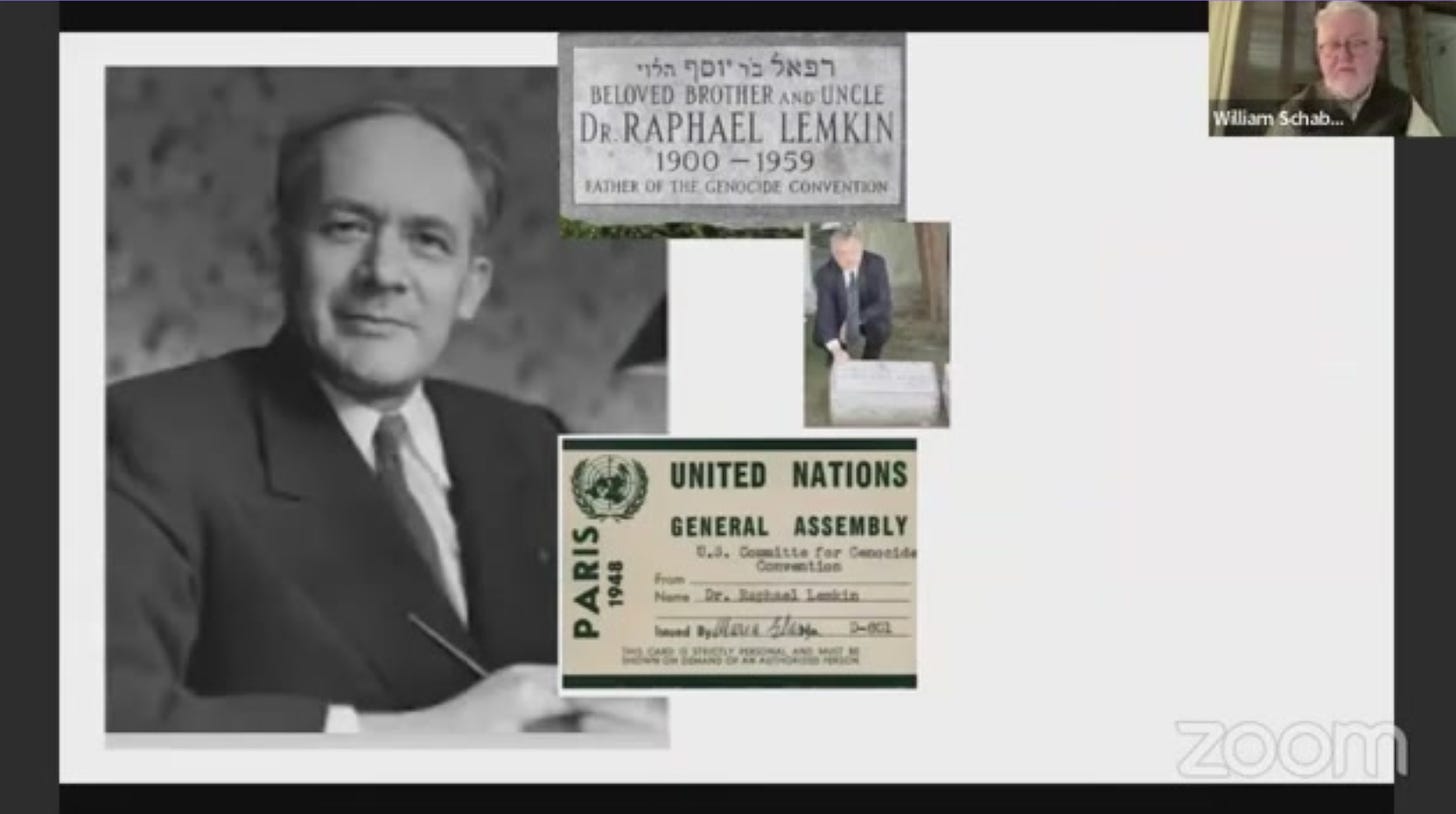

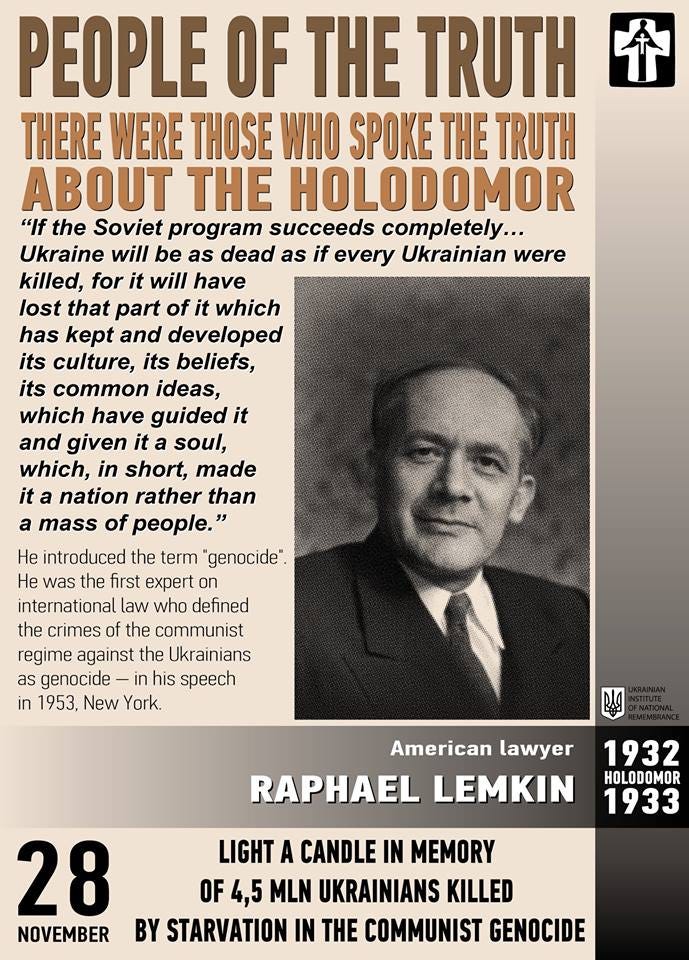

The Man Who Invented The Word Genocide - Raphael Lemkin

This is a picture of the man who invented the word genocide, Raphael Lemkin. He was himself a refugee from Europe, a Jew born in what is now Belarus, I think.

He went to university in Lviv in what is now Ukraine, and then fled, went to the United States and kind of reinvented himself.

He was a lawyer in Poland before the war. He became an academic, did a little teaching at American universities, and then he became an activist. And he spent the rest of his life from 1944 when he invented the word genocide until his death, campaigning for the adoption and then the ratification and entry into force of the Genocide Convention.

His role is an important one. He's an extraordinary individual, but it's important to understand that his vision of genocide does not correspond entirely to what was finally adopted as a matter of international law. And the international law, of course, was the creation of states to understand the notion of genocide, at least originally.

and its recognition as a legal concept, we have to go first to Nuremberg.

The Nuremberg judgment dealt with what we today think of as the genocide committed by the Nazi regime, but it did this only in a partial way.

The Gaps & Limits of Nuremberg Code

It did this in a partial way because the charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal, the legal framework that was used in the great trial, which took place in 1945 and until the 1st of October 1946, restricted the acts of persecution, the atrocities that were committed against Jews and against other minorities in Nazi Germany, and then subsequently in the occupied territories.

The acts committed in Nazi Germany prior to the outbreak of the war were excluded from the scope of the trial. The trial insisted that atrocity crimes, it used the term there also for the first time, crimes against humanity had to have a connection, we call it a nexus, had to have a nexus with the armed conflict.

That was the notion of crimes against humanity that was set out in the charter of the tribunal and that was confirmed in the judgment that was issued at the end of September and the beginning of October 1946.

Lemkin wasn't in Nuremberg when the judgment was issued, although others have said he was there. But we think now we seem to be pretty confident that he was in the American hospital in Noi in a or a Parisian suburb when he learned of the judgment, he rushed back to the United States where the General Assembly of the United Nations was about to open the second phase of its first session in New York. And he immediately started campaigning for the General Assembly to adopt a resolution on issue of genocide.

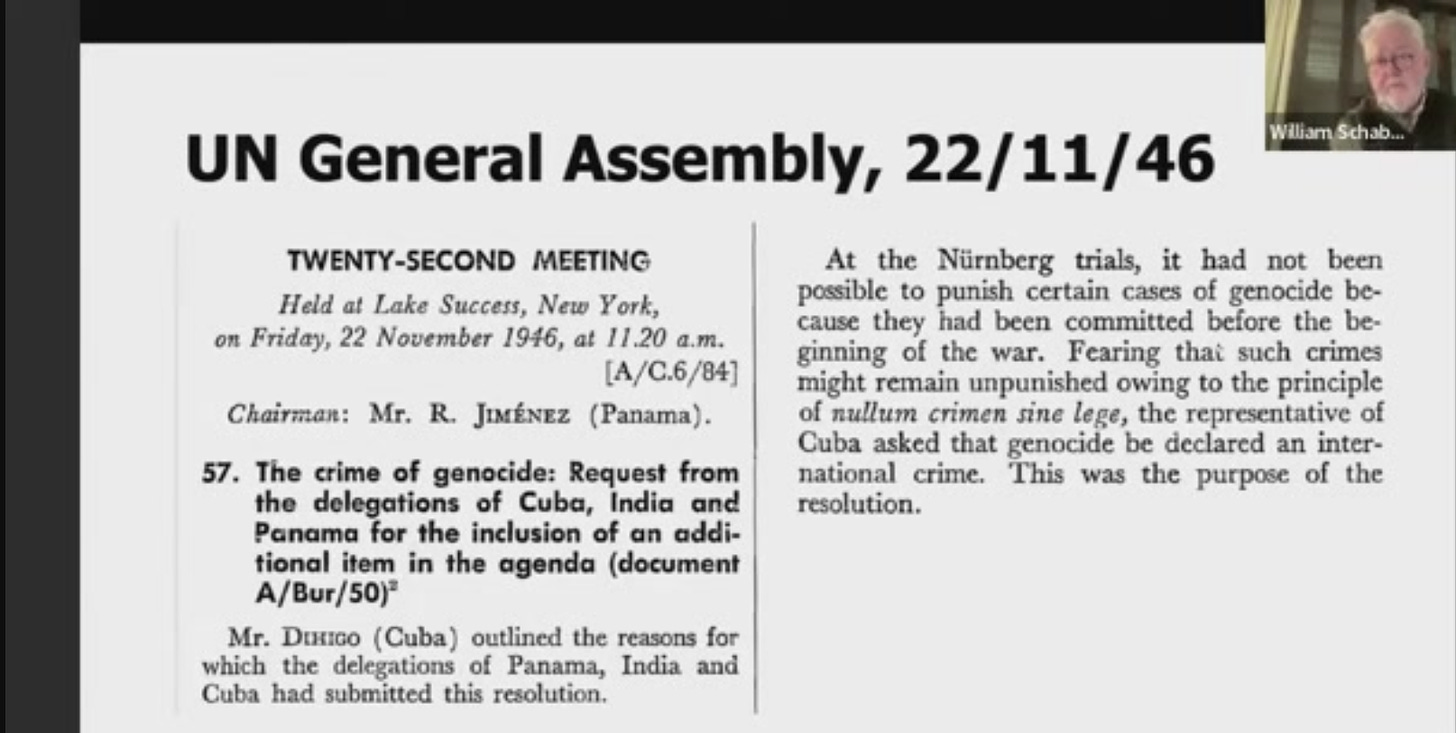

So here you can see on the screen from the summary records of the Sixth Committee of the General Assembly on the 22nd of November 1946, the Cuban ambassador rose to propose a resolution. He did it on behalf of Panama and India. We believe that the speech he delivered was actually written by Raphael Lemkin.

Lemkin had managed to recruit Panama, India and Cuba to support the resolution. And when he did this, the delegate from Cuba, Ernesto De Higo, said that at the Nuremberg trials, he expressly said, this is to correct a shortcoming in the Nuremberg trials, to fill a gap in the law that had been left by the Nuremberg trials, which was the possibility of atrocities like genocide being committed in time of peace.

I put up on the screen now the excerpt from the charter of the International Military Tribunal adopted on the 8th of August, 1945. That explains this. And you can see that crimes against humanity are acts committed, it says, before or during the war, but in the connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal.

And any crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal meant a connection with either war crimes, or crimes against peace. This was the connection that Nuremberg imposed on atrocity crimes like crimes against humanity, including the acts that today we would consider as genocide. So the question arises, why did this happen?

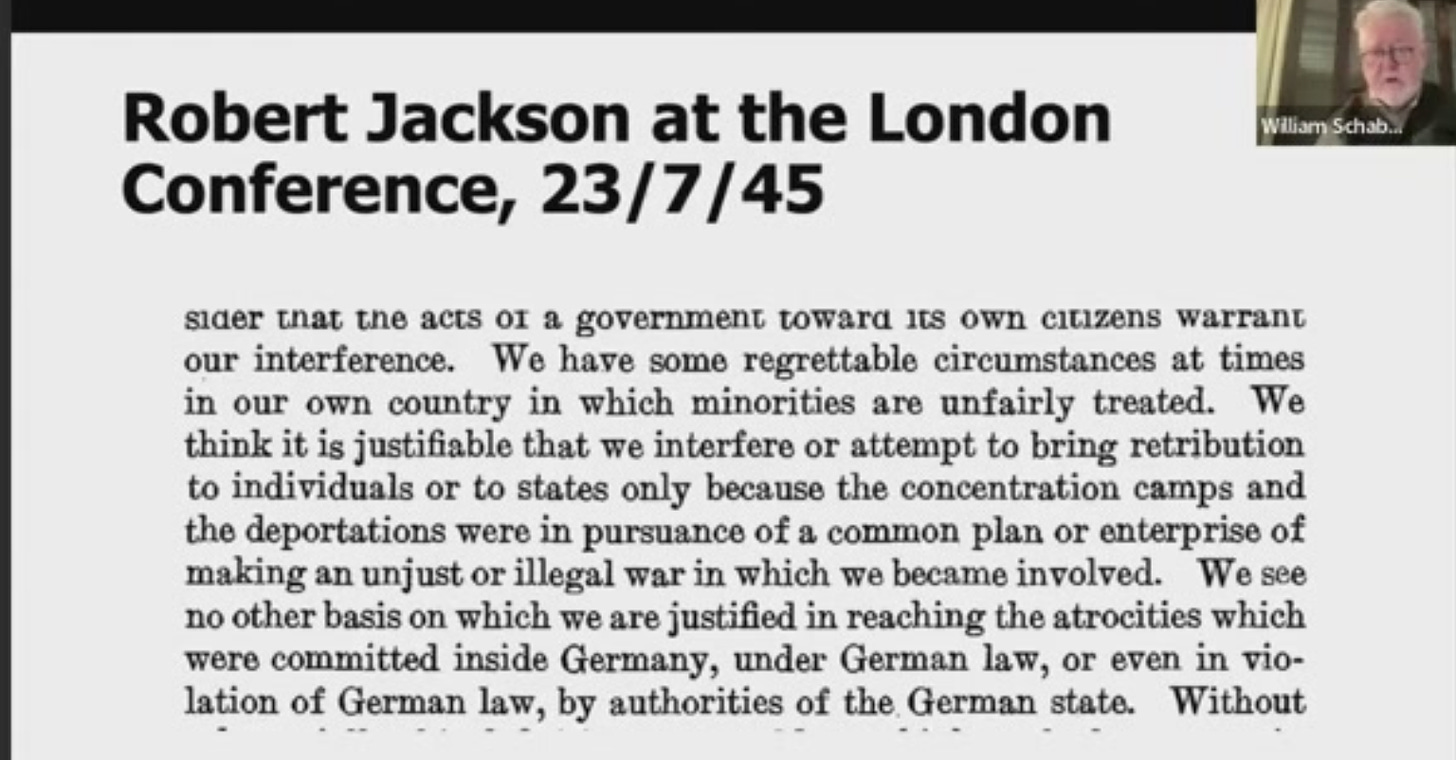

This is an excerpt from the minutes of the London conference where the charter of the Nuremberg tribunal was adopted.

Robert Jackson, who was the American judge sent by president Truman to represent the United States at the conference.

Jackson went on to be the prosecutor for the United States, explain why it was necessary to restrict the scope of the definition of crimes against humanity.

He said, and you can see it on the screen, we have some regrettable circumstances in our own country in which minorities are unfairly treated. And we think it is justifiable that we interfere or attempt to begin to bring retribution to individuals or to states only because the concentration camps and the deportations were in pursuance of a common plan or enterprise.

And you can see in the final line, he says, we see no other basis on which we are justified in reaching the atrocities which were committed inside Germany under German law or even in violation of German law by authorities of the German state.

And there you have it in a nutshell because the reason why Robert Jackson didn't want to recognize crimes against humanity in peacetime, because he was concerned that it would suggest that there was a precedent whereby atrocities committed inside the United States under American law, or even in violation of American law by authorities of the state would be recognized as crimes under international law.

United States Insists On Impunity For US Based Atrocities - & Gets Impunity!

And his colleagues around the table, the representatives of the United Kingdom, of France, and of the Soviet Union appear to have been of the same opinion.

And this is why it was three countries of the global South, which was not as robust a political force in 1946 as it is today, campaigned for recognizing, for filling this gap in the law of Nuremberg. And they were able to do this through the Genocide Convention.

One final slide, the Nuremberg judgment shows how the judges at the Nuremberg trial restricted and limited the scope of the persecution of the Jews, what we today call the genocide of the Jews, restricted them to acts committed subsequent to the outbreak of the war.

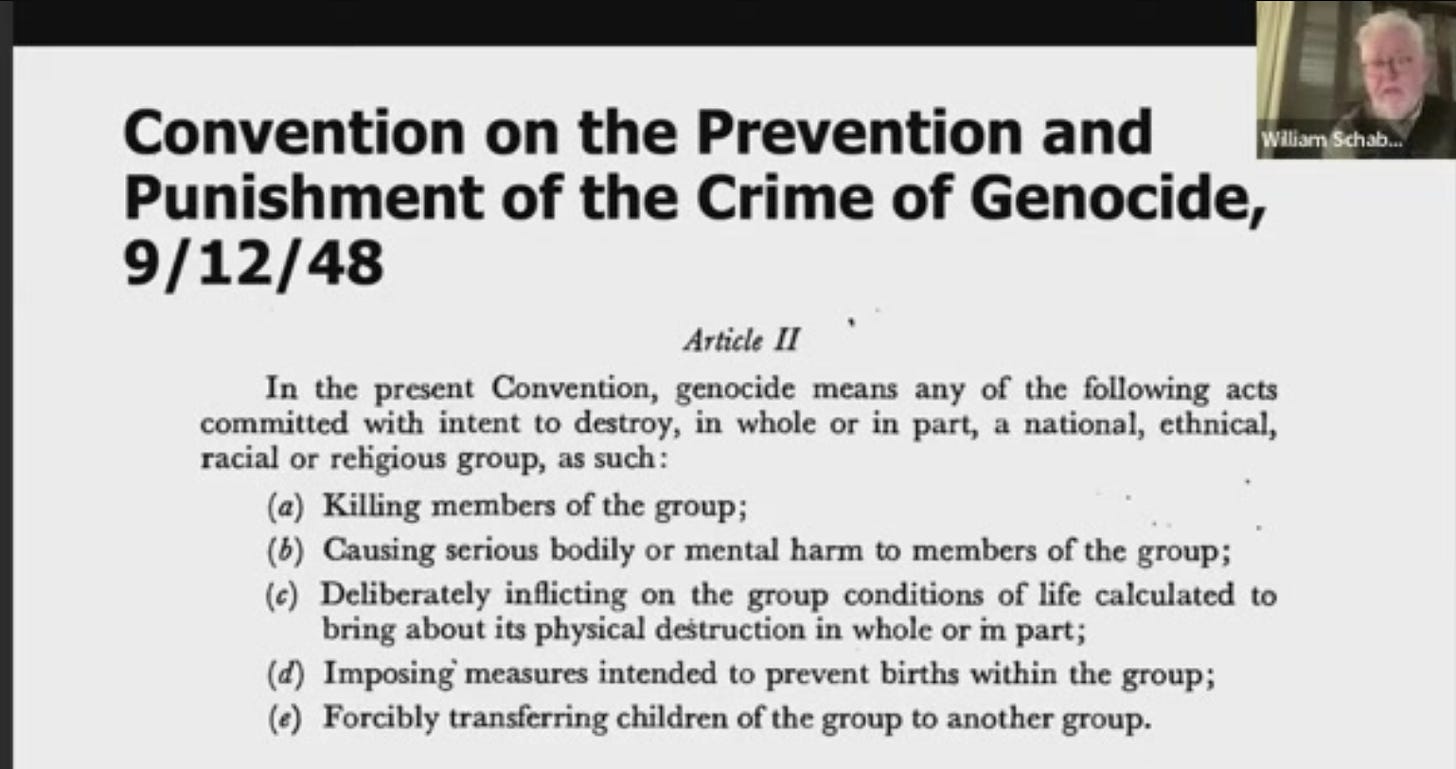

This is the heart of the Genocide Convention.

The Genocide Convention was adopted in 1948 on the 9th of December by the United Nations General Assembly, a unanimous resolution.

The text of the convention begins by stating that genocide is a crime that can be committed in time of peace, as well as in time of war. That was what was so entirely unique about it. It was the first international crime recognized that could be committed in time of peace and without a link to an international armed conflict.

In some ways, it resembles the notion of crimes against humanity that was prosecuted at Nuremberg, but it's certainly narrower because there was no way in 1948 that the United States, France, Britain and the Soviet Union who had resisted the idea that peacetime atrocities could be subject to international law, there was no way that they were going to change their mind entirely.

The price for doing so was, of course, a much narrower crime, a notion of a crime that is much, much more, much more, much narrower and much more difficult to prove for a number of reasons.

First of all, there is this requirement in the preambular paragraph that it must be committed with the intent to destroy in whole or in part a national, ethnical, racial or religious group. This is really the heart of the problems we have with genocide prosecutions and with cases under state responsibility before bodies like the International Court of Justice proving this intent to destroy with crimes against humanity.

We don't have to prove the intent to destroy. We don't have to prove destruction at all. Crimes Against Humanity deals with questions of persecution of a group. Crimes Against Humanity is also much broader because it not only covers a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group, but a range of other groups based on such things as political opinion, gender, and so on. And it's followed then by the list of punishable acts, killing members of the group, causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction and so on. It's rarely been very difficult to establish that one of these acts in the paragraphs in Article 2 is committed. The challenge has almost invariably been to prove that it was done so with the intent to destroy the group.

And I have seen even recently people have tried to argue that if you could prove that all five group, all five acts had been committed, that perhaps you didn't have to prove that it was done in fulfillment of the intent to destroy the group as such. But I don't believe that to be a really serious or credible interpretation.

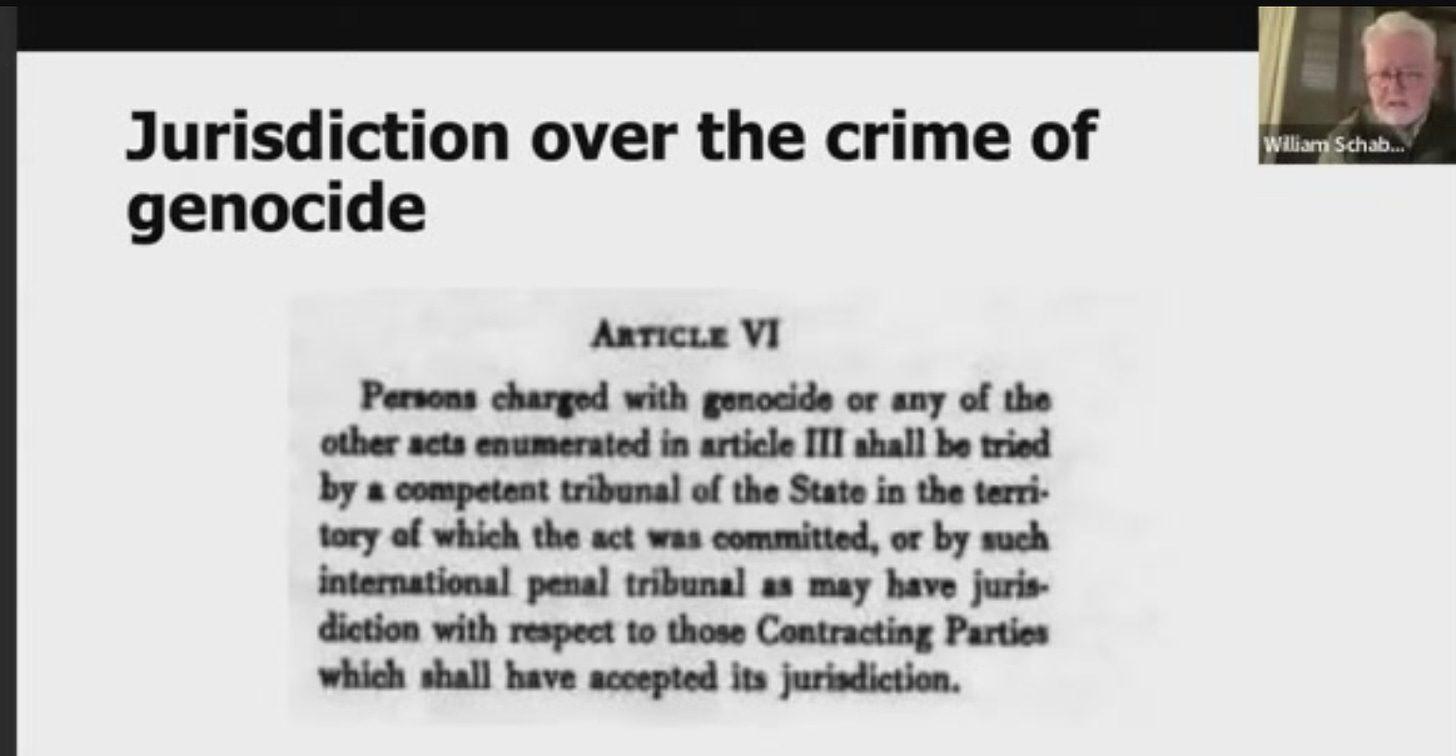

Now, one of the features of the convention that is of great interest is the prescription on how the crime is to be prosecuted.

The convention's title is the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. But really, most of the convention is about the punishment rather than the prevention.

The word prevention appears there, and it was subsequently given some flesh in, but judicially by the International Court of Justice in the 2007 case of Bosnia versus Serbia. But really the heart of the convention's provisions deal with the prosecution of the crime, the punishment of the crime in a criminal court.

And Article 6 is very restricted because it says that persons charged with genocide are to be tried by a competent tribunal of the state of which the act was committed, which in many cases would doom any hope of prosecution because presumably the state was involved in one way or another with the commission of the crime.

The article was adopted after attempts to introduce universal jurisdiction whereby any state would be empowered to prosecute the crime regardless of where it was committed and regardless of the nationality of the offender. But these were rejected by quite strong majorities. It was not a popular idea at the time.

Using Costa Rica Universal Jurisdiction!

In order to diminish perhaps the hopelessness of the idea that it would be prosecuted by the state where the act was committed, the convention also provided for an international penal tribunal to be created. One did not exist at the time in 1948. But in the companion resolution to the resolution adopted on the 9th of December 1948, containing the Genocide Convention, the General Assembly called upon the International Law Commission to study the feasibility of creating an international criminal court.

And if we're looking for the moment of conception, one could say, of today's international criminal court created by the Rome Statute, which was adopted 50 years later in 1998, it's Article VI of the Genocide Convention and the resolution adopted with it. Of course, it was a long story for that to ever come to fruition and result in the actual creation of a tribunal.

(31:35.629)

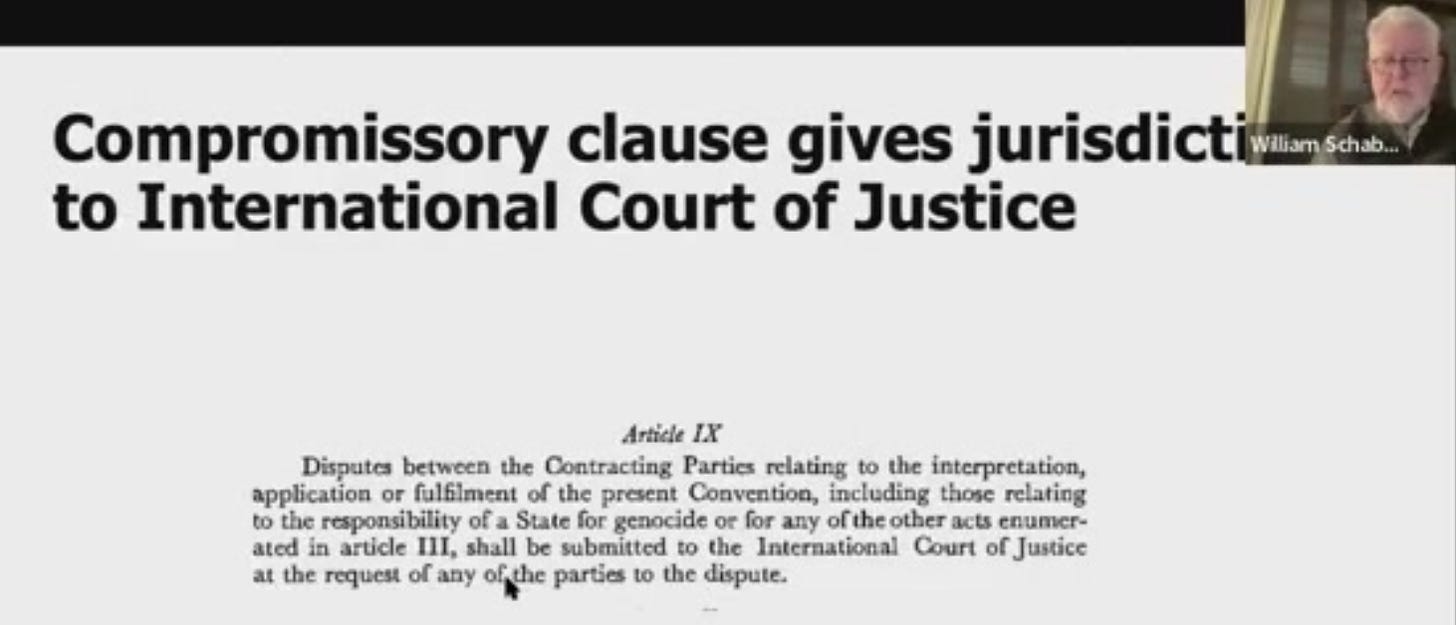

The other clause that is of great interest to us today because of these cases pending at the International Court of Justice is Article 9.

Article 9 compromissory clause for ICC

Article 9 is what we international lawyers call a compromissory clause because it recognizes the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice in settling disputes relating to the Genocide Convention. The International Court of Justice is the the world court, it's the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

All members of the United Nations are also parties to the statute of the international court of justice. But that doesn't mean that they accept the jurisdiction of the international court of justice. They have to do this by making general declarations. About one third of the member states have done so or specific acceptance in particular cases.

And also they recognize it through these compromissory clauses, which figure in a number of international treaties.

And so we have many states who have not accepted the general jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, but have accepted the jurisdiction of the court when the genocide convention is at issue. There are, think now about 140 such states.

So approximately double the number of states that have accepted in a general way the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice.

And so this is, for example, in the case between South Africa and Israel, Article 9 is the basis of the court's jurisdiction, as it was in some of the earlier cases, notably the two cases that led to important judgments of the court, the one filed by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia, that led to a judgment in 2007. And then the subsequent case, which in some ways replicated or echoed the case between Serbia and Bosnia, which was the case Croatia filed against Serbia with the judgment issued in 2015.

And in those cases, there was a great deal of frustration because the court came to the conclusion that it could not attribute genocidal intent to Serbia, that Serbia could not be therefore found to have committed genocide against Bosnia and Herzegovina or against Croatia.

And the unfortunate part of that for the applicant states was that the court then was without jurisdiction to make any other determination.

If it's a prosecution, a criminal prosecution, of an individual at the International Criminal Court, if genocide is charged and if the court is unable to reach the conclusion that genocide was committed, it can still convict an accused person of a lesser offense, an offense where the requirements are not as demanding, particularly crimes against humanity and war crimes.

But when the jurisdiction of the court is based exclusively on the genocide convention, it has no such option. And if it decides that genocidal intent is not proven to the requisite high standard, then it can only dismiss the case. So this is the challenge that is today confronting, particularly the Gambia in the case against Myanmar and the case of South Africa against Israel.

These cases are works in progress…

Now I want to say a few words about each one of these cases because this is a work obviously in progress and there are things that are happening almost every week in one or other of the cases. Gambia versus Myanmar case was filed in late 2019 and it led almost immediately within by January of 2020 to an order for provisional measures by the court.

The provisional measures order has a relatively low requirement before the court. It's relatively easy to obtain a provisional measures order because the court's standard is quite low for giving such an order.

It probably has the consequence that the orders are not very demanding in the case of Gambia versus Myanmar, the order was very largely in order to Myanmar to not to commit genocide, which is of course very desirable. But Myanmar's simple answer to that would be we didn't commit it before and we're not going to commit it in the future. we're not allowed, we'd be in violation of the law were we to do so.

It's, I think normally in a domestic legal order, I had experienced myself for many years practicing as a lawyer, you would obtain a provisional measures order to stop someone doing something which they're legally entitled to do.

And we can see this also at international human rights courts like the Inter -American Court of Human Rights or the European Court of Human Rights, where it's not unusual to have an order of interim or provisional measures ordered

[SIDE NOTE - IOJ IS GOING TO INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS & PRAYING FOR PROVISIONAL INJUNCTIONS TO STOP THE SHOTS/PCR - PRAY FOR JUSTICE - THEY CAN DO IT FOR US ALL].

But as a general rule, those are orders to a state not to do something that it's otherwise entitled to do, such as expelling someone from its territory. So all of this is to say that it's not that challenging to obtain a provisional measures order. The legal effect of them may not be great, but the political effect of them is enormous, absolutely enormous.

And this was evident in Gambia versus Myanmar with the order that was filed in January of 2020. In that case, the case has now worked its way through an initial stage of preliminary objections.

And now the parties are finalizing their submissions. I think that this has to be completed by sometime in 2025, and then the court may order another round of written submissions.

This is possible, although it's not done in every case. So I think that we're probably looking at a hearing in the Gambia versus Myanmar case at the end of 2025 or sometime in 2026 with a judgment perhaps by the end of 2026.

And I think that that judgment will largely set the tone that will then prevail in the case of South Africa versus Israel.

Let me say more about that in a minute, but since I'm proceeding chronologically, let me just say a few words about the Ukraine versus Russia case.

Ukraine versus Russia was filed with a very creative approach to the genocide convention in that Ukraine did not charge Russia with committing genocide.

Ukraine said that Russia has invaded us and they have used the prevention of genocide as a pretext or as a justification for doing so. And this is a false pretext because we haven't committed genocide.

What Ukraine was trying to do was to get an order against Russia indirectly through the genocide convention, but really one dealing with the invasion itself with the use of force. And it was successful in obtaining a provisional measures order against Russia.

As I say, this was not, as we can all, as we all know, was not effective in a practical sense, but it was politically quite effective and quite helpful to Ukraine.

But subsequently, a big part of that case has now been thrown out because at the preliminary objection stage, which resulted in a judgment at the beginning of this year, the International Court of Justice in effect said, yes, you cannot use the Genocide Convention to indirectly address an issue of an invasion or of aggression.

But they said, so we're going to stop that part of the case. They said, there's another part of the case, which is that you're saying you didn't commit genocide, and you're entitled to try and prove that.

So Ukraine finds itself now in, I think, an uncomfortable position of having to try and prove to the satisfaction of the judges that it didn't commit genocide. And the whole world knows that it didn't commit genocide. So the exercise of doing this is not really particularly helpful or useful. And Ukraine itself has set too high a standard because Ukraine itself set the set the goalposts in a way for the case, and they have said that there's no evidence that they have committed genocide, then I think that's not a straightforward thing to prove.

(41:24.501)

I'm not suggesting that Ukraine committed genocide, but that's not the same thing as proving that there's no evidence of it. It's a very difficult proposition. So that's where this is an unusual case, and it's even uncertain whether Russia is going to continue to participate in it.

The third case, South Africa versus Israel. This is in many ways going to be influenced by the outcome in the Gambia versus Myanmar case to the extent that the judges of the court are prepared to adopt a more flexible and liberal approach both to the substance of the charge of genocide and to the requirements for the proof of genocide, a more liberal approach than they took in the two cases dealing with the former Yugoslavia, the one filed by Bosnia and the one filed by Croatia.

There are indications that this can happen. Some of the indications come from the many interventions by states, which is completely unprecedented. We've never had this before, but in effect, the states that are parties to the genocide convention are telling the court, this is what we think the definition of genocide is. I believe this is going to influence the court. So I think that it's quite reasonable to expect the court to revisit its approach to genocide and to adopt a more generous and liberal approach to it.

The other thing I think in the South Africa versus Israel case is that of all of the cases that have been taken before the court, Gambia versus Myanmar, the cases filed by Bosnia and Herzegovina and by Croatia, I think this is probably the strongest case.

I think it's the strongest case because we have not only the outrageous statements of the Israeli leaders talking about how every Palestinian is an enemy, how they're going to deprive Gaza of water and of electricity and of food and so on.

These types of statements sometimes feature in many conflicts, but there are a lot of them in South Africa versus Israel. But they're coupled also with a clear policy of the current leaders of Israel, the Netanyahu government, which is to reject entirely a two state solution, to reject entirely the possibility of self -determination for Palestine.

And that means that they're talking about a state with borders that will go from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea and as long as the Palestinians are still there, they will either be in the majority in that state or close to it. And this is something that they will not be able to. These things don't work. They don't work together. And I think all of these point to the fact that the Israeli leaders currently have to, in some way or another, get rid of the Palestinians in Gaza and in the West Bank.

And with the borders closed as they are, where it's essentially impossible for the people of Palestine to go elsewhere, combined with this need, which is expressed in many different ways, to get rid of the people of Palestine, I think we're very much, we're in one of the most compelling cases for genocide taking place.

(45:47.745)

This will, we will have to wait to see the evidence in the case and how things play out in the, because it's a dynamic and fluid situation.

But I would think that that case probably, certainly if Gambia is successful against Myanmar, it seems impossible that South Africa will not be successful against Israel.

But even if Gambia is not successful against Myanmar, I think that South Africa has a more robust and a stronger case.

And then finally, we have this very interesting case filed by Nicaragua versus Germany, which focuses on issues like German complicity and through support for Israel and on Germany's failure to prevent genocide because of its influence over Germany.

And this is an issue that really results from the judgment of the International Court of Justice in the Bosnia versus Serbia case in 2007.

In that case, the judges concluded that they could not attribute genocidal intent to Serbia. At the same time, they recognized that genocide had been committed within Bosnia and Herzegovina when the Srebrenica massacre took place in July of 1995. And in so doing, they were simply following the conclusions of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. So they endorsed them, but they said, we can't blame Serbia for this. This was the work of the Bosnian Serb forces. And they said, we don't have the evidence that Serbia was in control and was directing the Bosnian Serb forces in the commission of genocide.

But they went on and essentially developed a doctrine about the prevention of genocide, where they said that Serbia, because of its relationship to the Serbs in Bosnia, its influence over them, that it had a duty to prevent genocide and that it had failed in doing so. And so there was a finding against Serbia for its failure to prevent genocide under the convention. It was really quite a radical conclusion because it was saying that that duty to prevent genocide applied outside the territory of Serbia. That Serbia was responsible for acts that it did not commit and that took place outside its own territory.

In the judgment in 2007, the judges referred to some other treaties where there's an obligation to prevent the crime. They pointed to the torture convention and to some other and counterterrorism conventions.

And so they said, so there's nothing particularly innovative about what we're proposing, but there certainly was because there's no treaty where a state has an obligation to prevent acts that take place outside of its territory, where it has an explicit obligation.

And so this was a very important, a marvelous creation, really, from the standpoint of enhancing human rights law.

And there are obvious applications of this to the situation in Gaza, not just in Gaza, but in the whole of the occupied Palestinian territory.

And there have been attempts to take this case to court in domestic proceedings in the United States, but these are very difficult.

But it's at the root of the case filed by Nicaragua versus Germany. Germany, because of its position of influence, is in violation of the Genocide Convention for its failure to prevent genocide in Gaza. It's not alone in those circumstances.

And I expect that there are lawyers and governments, many Western governments who are anxiously studying that case because of their own vulnerability. The United States is immune to prosecution at the international level for this because the United States is one of a handful of countries that ratified the Genocide Convention, but with a reservation to Article 9, which is the article that gives them jurisdiction gives the International Court of Justice jurisdiction. For that reason, I think that if it was different, and if the United States had not made that reservation, I am sure that Nicaragua would have taken the case against them at the International Court of Justice as well.

So this final slide, think I've spoken to these points and I won't repeat it.

Let me just say in conclusion that we're in a fascinating period, more generally a fascinating period of international law with this turn towards the International Court of Justice and more generally towards judicial mechanisms to address disputes that were previously settled at the political level.

And this is taking many forms. I've spoken already a lot about Palestine. And you may know that one of the other important developments in international law is the advisory opinion by the International Court of Justice issued on the 19th of July of this year, in which it declared, of course, straightforward that the occupation of the Palestinian occupied territory is not only contrary to international law, but that it has to be brought to an end as soon as possible.

And it's my understanding that there is now an effort to have a resolution in the General Assembly adopted in the coming weeks that will call for that, that will support that and will use that.

There's a great, a lot of lot of battles going on at the judicial level.

They don't solve all of the problems, but they do change the temperature politically.

And in that way make a contribution both to preventing genocide and to promoting world peace.

And with that, I think I'm going to conclude, and we have perhaps a few minutes left. If there are any questions, I'd be very happy to try and address them.

(52:53.709)

Thank you so much, Professor Chabas. This was an illuminating lecture and it is very positive to listen to you when you mentioned that we are in an interesting period for international law and you see relevant developments in the international protection of human rights.

Most of the press comments and the general opinion tends to say that the institutions are not coping with the challenge, are not being able to handle matters properly.

IOJ is raising the funds to sue for crimes against humanity and a covid reckoning. All assistance to step up & help the cause as a partner in justice is deeply appreciated.

Paid subscriber/donors make everything happen!

Justice isn’t free - It takes joining together to raise the necessary Attorney fees from the community!

To support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber or donate.

ANOTHER VERY IMPORTANT ARTICLE

And another critical article, since we are speaking of Israel, Nuremberg, Crimes Against Humanity & Genocide:

END OF POST!!!!!!

Further reading on Professor Chabas and the issue of retroactivity for the die hards:

The HISTORY Of The Most Important Authority On The Matter Of Genocide and International Law: Professor Chabas

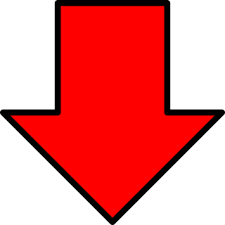

I want to say just a few words about my own interest in the subject. People often ask me, why did you, how did you get involved in this? I had finished my PhD in late 1992. It was on the issue of the death penalty. It had nothing to do with genocide. And this was not a subject to which I had given any great attention. And I found myself in January of 1993, visiting Rwanda as part of a human rights fact -finding mission, we issued a report upon the conclusion of our mission at the end of January. First, we issued a a press release that I helped to draft, and then a report where we warned of the danger of genocide in Rwanda.

And this was a controversial statement. And When challenged on it in this commission of inquiry, people turned to me and said, well, you're the guy with the PhD in international law. Tell us what it means. How do you interpret the genocide convention? And I was not in a position to give a serious, credible answer. It was something that I knew little about. I was embarrassed in a way that I wasn't able to provide a better explanation.

And so I set to work studying it and discovered then in 1993 and then later when the genocide did take place in 1994 that there had been very little academic activity devoted to the genocide convention, academic and judicial, since the 1950s. In effect, there had been no serious study of a book length. There had been a few journal articles.

But most of the writing about genocide in the Genocide Convention was outside the discipline and was the work of historians and social scientists. And so I set to work writing this book, which was finally published in 1999 and which is now about to appear in its third edition. But there's another more maybe personal explanation.

This is the name of my great aunt, Hindakomal. She was born with the surname Shabas, spelled in a different way than I spell it. I inherited the spelling from my father and my grandfather, but my grandfather's brothers and his sister wrote the name differently. Hindakomal's surname was the name of her husband.

She married in Germany in the 1920s. Well, I'll show you on the screen a very complicated family tree and I wouldn't expect you to sort it all out, but you might see it towards the bottom there that Hind Kamal, in fact, was married and then divorced from her husband in 1934 and then remarried him in 1945.

The explanation is that Hindukumul, my great aunt, was a Jewish woman living in Berlin. And in effect, she was taken into hiding and lived in Berlin through the war. There were about 1 ,000, perhaps, maybe a few more Jews who survived the war in Berlin. And there were some elsewhere in Germany, and she was one of them.

You can see I've put on the side of the screen an excerpt from the judicial file that I found in Germany where she was forced to change her name in 1938 to add the name Sarah. And this was a requirement that the Nazis imposed on all Jewish women as a form of identifying them. And she would have worn the yellow star as all Jews had to do as well at the time. So I have a personal interest obviously in this subject of genocide.

The Issue Of Retroactivity:

And one other issue which is quite often also brought is do you agree that we can have genocides committed even before the convention? So for instance, the... the Herero case before the First World War and the Armenian genocide, it would be very frustrating to say that we cannot talk about genocide because the crime was only typified in the 1948 Convention. So this is a first comment if you like to talk about it shortly, please.

Yes, thank you. Thank you for that question. Well, I don't have any difficulty at all using the term genocide, using the definition of genocide that was adopted in the 1940s to speak about historic events. It was always ambiguous whether the Genocide Convention could apply retroactively.

The general rule in international law is that there's a presumption of non -retroactivity, but some treaties do apply retroactively if the context suggests them. one might have, there was a good argument, I thought, that the convention itself could apply retroactively. But in the 2015 judgment of the International Court of Justice, they declared that that's not the case. So I think that issue was settled, but the Genocide Convention itself speaks about genocide being committed at all times in history.

Moreover, the resolution that led to the Genocide Convention, which was adopted in December of 1946 by the General Assembly of the United Nations, was a declaratory resolution. It was well understood then and still is today, that the General Assembly is not really a legislative body, but a body that it cannot create law. And that's not what it was doing in 1946. The resolution that was adopted in December of 1946 that then led two years later to the convention was declaring what the law was in December of 1946. And it said genocide is a crime.

If it was a crime on the 11th of December, 1946, then it must've been a crime on the 10th of December, 1946 as well. And on the 9th of December, 1946 and so on. So I think there's a very compelling argument that genocide was a crime under international law prior to 1946. How far back we can go is a matter of some debate, although of perhaps not much practical interest. We're not going to prosecute anybody for murdering the Herrero in 1904. We're not gonna prosecute anybody for murdering the Armenians in 1915. So it's really more of a theoretical proposition, but there's nothing wrong with using the term genocide to speak about past events.

We might also distinguish between the crime of genocide and genocide to cool. And we have examples going back to the destruction in Mitalini by the Athenians in, I don't know when, a very long time ago. Yes, thank you. And also the ethnic cleansing that Azerbaijan carried out this year against the Armenian population that they were literally thrown out of the homeland in a very short and brutal notice, leaving no option. Either you leave now or you are dead. So this is something which was quite shocking, even if we don't have the genocide featured as such, but this ethnic cleansing was very beyond what everything that could be argued as legitimate for the protection of the Azeri side. I don't know if my colleagues and co -organizers have any comments, questions. I don't want to monopolize Professor Chabas all to myself.

Well, yes, I just want to say I do have to leave very shortly. had booked one hour and I have to catch a short. Professor Paul, if I could ask a very quick question.

Please, sure. Okay, Professor Schaap as well, thank you very much for the historical approach. I'm a historian, I work with Arab and Palestinian history, so that was very, very enlightening, very interesting. Thank you very much. And a short, quick question. What would you view, possibly suggest, as a measure that Brazil as a country could do to help end the genocide in Palestine through judicial, international court of justice and so on measures. What would be the most practical and effective measure in this case, in your view?

Brazils Important Role?

Well, I assume that Brazil is not providing any, is not selling weapons or providing weapons or making a contribution in that way, which is the case. I'm coming to you from France. I'm going to the United Kingdom this evening. That's a real issue here in Europe, but I doubt that that's of any practical consequence. I would think that Brazil should intervene in the case of South Africa versus Israel. I think your president may have already made a statement to that effect that it was considering doing so or would like to do so. I think that is a very practical significance. I think that there are many, many states now that are doing this, that are intervening in different ways in this litigation. And it's important. And you don't want to be left out either.

(01:01:07.501)

Well, thank you very much for your opinion, Professor Saba, thank you very much.

Aalo, I think you have your microphone on, yeah.

Now it's open. Okay, this is, we don't want to cause any trouble for your training later today. So thank you so much again, and we hope to keep in touch and make another activity in the coming year. Maybe this would be great. So thank you so much. And this, with your permission, this, lecture was recorded and will be reachable for further listeners in the series of the Permanent Forum on Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity of the University of Sao Paulo.

So thank you so much for your contribution and hope to see you soon again. Thank you. Thank you for having me. Thank you very much.

So we can now close today's session and be prepared for the next sessions in September, in October and November this year. So bye -bye to my colleague, co -organizers and to the audience today.

And Professor Schaubers, great thanks from all of us. Bye -bye.

![How Is Nuremberg Code Enforceable? Court Hearing ORDERED For November 9, 2023 To Take Covid-19 [non] Vaccines OFF The Market](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa18194fd-abc3-4e8c-9cd6-c532d2830eb2_474x316.jpeg)

UNITE WITH GOD AND HIS LIKE MINDED PRAY AND PREP,,,, TIME TO COG - CORRECT OUR GOVT.

Thank you! Thank you! 🙏🙏🙏